Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- 1. World-Class Camouflage That Fools Almost Everyone

- 2. The Windy-Day Sway: Behavioral Camouflage

- 3. The Dramatic Escape: Self-Amputation and Limb Regeneration

- 4. Chemical Warfare: Smelly Sprays and Defensive Secretions

- 5. Startle Displays, Spines, and Other “Don’t Mess With Me” Warnings

- 6. Extreme Sizes: From Tiny Twigs to Giant Tree Monsters

- 7. Cloning Themselves: Reproduction Without Males

- 8. Egg Mimicry and Ant Babysitting Services

- 9. Long-Distance Travelers: Surprising Ways They Spread

- 10. Surprisingly Good Pets with Chill Personalities

- Putting It All Together: Quiet Insects, Loud Superpowers

- Real-World Experiences with Stick Insects

At first glance, stick insects look like the lazy interns of the insect worldlong, skinny,

and apparently doing nothing but hanging around on twigs. But behind that “just a branch”

aesthetic is a set of survival skills so wild that even sci-fi screenwriters might tell them

to dial it back a little.

Also known as walking sticks or phasmids, these insects have evolved some of the most

sophisticated camouflage, defense systems, and reproductive tricks on Earth. There are more

than 3,000 known species scattered across forests, shrublands, and backyards around the

globe, and many of them are hiding in plain sightliterally. From regrowing lost legs to

reproducing without males, stick insects are quietly rewriting the rules of what a “simple

bug” can do.

Let’s climb into the bushes (metaphorically, no poison ivy required) and explore ten

incredible abilities of stick insects that prove these “walking twigs” are anything but

boring.

1. World-Class Camouflage That Fools Almost Everyone

Camouflage is the stick insect’s signature move. Many species have evolved bodies that

look exactly like twigs, stems, or dried leaves. Their colors match bark and foliage, and

their legs line up with their bodies to complete the illusion. Some species even have

bumps and notches that mimic buds, scars, and knots on branches.

In zoos and insect exhibits, visitors often stare right at a stick insect enclosure and

confidently declare, “There’s nothing in there.” Then the “branch” suddenly walks away.

That’s how good they are. Studies of phasmids show that this extreme camouflagecalled

crypsisis the main reason such a large, slow, crunchy snack can survive

in forests full of birds, lizards, and hungry mammals.

Some species don’t just look like plants; they behave like them. Which leads us to their

next trick.

2. The Windy-Day Sway: Behavioral Camouflage

If you’ve ever watched a stick insect when there’s a breeze, you may notice something

strange: it gently rocks back and forth as if it’s being pushed by the wind. This

rhythmic swaying isn’t a sign of dizzinessit’s advanced behavioral camouflage.

By swaying in time with leaves and branches, the insect smooths out the tiny

“mechanical” movements that would give it away as an animal. Predators scanning for the

sharp, purposeful motions of prey instead see a plant part moving just like everything

else around it. Some research suggests that this swaying also helps them judge distances

and depth, but the main benefit is simple: if you move like a leaf, you get treated like

a leaf.

It’s the insect version of joining a crowd and copying everyone’s walk so nobody notices

you’re the one carrying the snacks.

3. The Dramatic Escape: Self-Amputation and Limb Regeneration

Imagine escaping danger by literally dropping a leg and running away. For many stick

insects, that’s not a gruesome accidentit’s a strategy. When grabbed by a predator, some

species can perform autotomy, a controlled self-amputation. Special

muscles snap the leg off at a weak joint, leaving the twitching limb behind as a decoy

while the insect makes a very uneven but urgent getaway.

Even more impressive, young stick insects can regrow the lost leg over several molts. As

they shed their exoskeleton to grow, a new limb develops and gradually returns to full

size. In some species, even older individuals can trigger an extra molt in order to

regenerate a missing leg. It’s like having a built-in “undo” button for bad encounters

with hungry birds.

Of course, this isn’t freeregrowing a leg costs energy, and repeatedly dropping limbs is

a bad long-term plan. But in a life-or-death moment, sacrificing one leg to save the other

five is a trade most stick insects are willing to make.

4. Chemical Warfare: Smelly Sprays and Defensive Secretions

When camouflage fails and physical escape isn’t an option, some stick insects switch to

chemical warfare. Certain species produce foul-smelling or irritating secretions from

glands near the thorax. These sprays can be squirted toward a predator’s face, targeting

sensitive areas like the mouth and eyes.

One well-known example is the spiny stick insect Eurycantha calcarata, which

can release a strong, musty odor when disturbed. Other species produce milky defensive

fluids with bitter or irritating compounds. To a predator, it’s like biting into a

mouthful of perfume and hot sauce at the same timememorable, but not in a good way.

Combined with their camouflage, these chemical defenses create layers of protection: if

a predator manages to find them and grab them, it may quickly decide that this

particular “twig” is not worth the headache.

5. Startle Displays, Spines, and Other “Don’t Mess With Me” Warnings

Not all stick insects rely on staying invisible. Some species have dramatic

startle displays they unleash at the last second. A normally dull,

bark-colored insect may suddenly spread bright wings patterned in vivid reds, yellows, or

blues. The sudden flash of color can confuse or scare a predator long enough for the

insect to drop, run, or hide.

Other species have sharp spines on their legs and bodies. When threatened, they brace

themselves and use those spines like miniature barbed clubs, pinching or stabbing at

anything trying to eat them. Some can also make hissing sounds or rustling noises by

rubbing body parts togetheran insect way of saying, “Back off, I’m pointier than I look.”

Stick insects may look gentle, but plenty of them come equipped with hidden armor and

a flair for dramatic theater when cornered.

6. Extreme Sizes: From Tiny Twigs to Giant Tree Monsters

Stick insects come in a shocking range of sizes. Some are only a couple of inches long

and delicate enough to perch on a grass blade. Others look like mobile tree branches.

Several of the world’s longest insects are phasmids, including species that can stretch

over 20 inches (with legs fully extended).

Recently, scientists in Australia described a gigantic stick insect more than 40

centimeters long that had managed to go unnoticed thanks to its superb camouflage. In

the dark rainforest canopy, it simply blended in among the branches, despite being the

size of a small snake.

This size variation isn’t just for show. Larger bodies can deter some predators, while

small and slender species can vanish into thin stems and fine foliage. Either way, stick

insects prove that “looking like a stick” can mean anything from “toothpick” to “small

walking broom handle.”

7. Cloning Themselves: Reproduction Without Males

Stick insects don’t always bother with traditional dating. In many species, females can

reproduce through parthenogenesis, a form of asexual reproduction where

eggs develop into healthy offspring without ever being fertilized by a male.

In populations where males are rare or absent, a single female can found an entire

colony. She lays eggs that hatch into genetic copies of herself, which then grow up and,

in turn, lay more eggsno courtship, no awkward first dates, no shared Netflix account to

untangle afterward.

This cloning strategy is incredibly powerful for colonizing new areas. If a pregnant

female is blown by a storm into a new forest or transported accidentally by humans, she

doesn’t need to find a partner to establish a thriving population. The downside is lower

genetic diversity, but for a stealthy insect living a slow, leafy life, it’s apparently

a workable trade-off.

8. Egg Mimicry and Ant Babysitting Services

Even stick insect eggs are clever. Some species lay eggs that look like tiny plant seeds.

On the surface of each egg is a nutritious cap called a capitulum, which ants

find irresistible. Worker ants carry the eggs back to their nest, bite off the edible

cap, and discard the rest of the egg in their underground “trash room.”

For the stick insect, this is perfect. The egg ends up protected in a secure, humid,

predator-free environment beneath the soil. When the nymph eventually hatches, it climbs

up out of the ant nest and into the vegetation above, starting its life with a free

ride and early protection.

This strategycalled myrmecochory, or ant-mediated seed dispersalis

more commonly associated with plants. Stick insects have essentially hacked the system,

turning ants into accidental babysitters and egg relocation experts.

9. Long-Distance Travelers: Surprising Ways They Spread

For insects that can’t fly (many stick insects are wingless), you’d think their travel

options would be limited. Yet stick insects have turned out to be surprisingly good at

spreading across islands and even oceans.

One reason is their tough eggs. Some species produce eggs with hard shells that can

survive drying, rough handling, or even a trip through a bird’s digestive system. There’s

evidence that eggs can be transported in soil, stuck to plant material, or carried by

wind and water over long distances.

Humans unintentionally assist them, too. Ornamental plants, cut branches, and landscaping

materials may hide adults or eggs. That’s how some stick insect species have turned up

far away from their native ranges, quietly turning new neighborhoods into their personal

camouflage playgrounds.

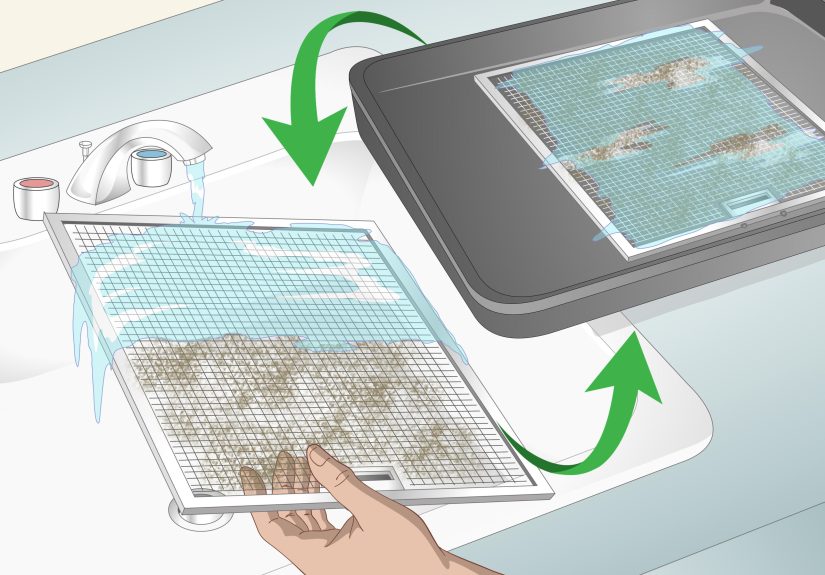

10. Surprisingly Good Pets with Chill Personalities

Despite their strange abilities, many stick insects are popular as educational pets and

classroom animals. They’re generally quiet, harmless to humans, and content to hang out

on a branch all day snacking on leaves. Their slow, deliberate movements and excellent

camouflage make them perfect ambassadors for teaching kids about adaptation and

evolution.

In captivity, they’re often fed bramble, oak, eucalyptus, or other leafy branches placed

in water. Because they’re nocturnal, many spend the day frozen in classic “I am a stick”

mode, then become active at nightclimbing, feeding, and occasionally molting. Molting is

a dramatic event where the insect hangs upside down and carefully wriggles out of its old

exoskeleton, sometimes leaving behind what looks like a ghost-stick suspended on the

branch.

For people who keep them, there’s a quiet joy in watching an insect that doesn’t buzz,

bite, or stingbut can still pull off some of the most advanced survival tricks on the

planet.

Putting It All Together: Quiet Insects, Loud Superpowers

When you add it all upexpert camouflage, behavioral tricks, limb regeneration, chemical

defenses, dramatic startle displays, extreme sizes, cloning reproduction, ant-assisted

childcare, rugged eggs, and relaxed pet potentialstick insects start to look less like

“boring brown bugs” and more like a highlight reel of evolutionary creativity.

They survive by being almost invisible, yet their biology is anything but dull. The next

time you walk through a forest or past a hedge, remember: some of those “twigs” may be

watching you back, perfectly still, ready to sway in the breeze the moment you look

away.

Real-World Experiences with Stick Insects

Seeing a Stick Insect for the First Time

Ask people who’ve actually encountered stick insects, and you’ll hear a familiar theme:

confusion, then wonder. Many describe their first sighting as a double-take moment. You

notice that one particular twig seems to be in a slightly different position than a

second ago. You stare at it, your brain glitches for half a second, and then it hits

you“Wait, that branch has knees.”

In nature centers and museums, educators often use this moment of realization as a

teaching tool. They let visitors search the enclosure themselves before pointing out the

insects. The quiet gasp when a “stick” suddenly moves is exactly the kind of emotional

hook that makes people remember lessons about adaptation and evolution long after they

leave.

Keeping Stick Insects as Pets

For hobbyists, keeping stick insects is a bit like having living, low-maintenance

houseplants that occasionally shuffle around. Proper care still matters: they need the

right temperature and humidity, a steady supply of safe foliage, and enough vertical

space to molt successfully. But compared with many other exotic pets, they’re fairly

forgiving and gentle.

Owners often describe them as calming to watch. At night, you might see a small group

slowly exploring their branches, carefully testing each step with their long legs. You

may witness a molta surprisingly athletic event where the insect hangs upside down,

pulls itself out of its old exoskeleton, and then slowly stretches its new body and

legs. Afterward, the fresh exoskeleton looks smooth and slightly soft, hardening over

the next few hours.

Some species can be handled with care, especially larger, calmer ones. Children

frequently describe the sensation as holding a moving twig or feather-light robot.

Because stick insects don’t bite or sting, they can help nervous kids build confidence

around insects in general.

Watching Their Superpowers in Action

In both the wild and captivity, patient observers can see many of the abilities described

above. You might watch a stick insect sway gently in artificial breeze from a fan, its

movements perfectly synced with the leaves. If you look closely at a younger individual,

you may notice a leg that’s slightly smaller or paler than the othersa regrown limb

from a past accident.

Egg laying is another fascinating behavior. Females may simply drop eggs to the ground

one by one, each tiny capsule designed to survive weather, predators, and, sometimes,

ant relocation. If you raise them at home, you quickly learn that what looks like a

container of sand or soil may suddenly sprout miniature stick insects months later, like

a time-delayed magic trick.

Why They Stick in Our Memory

Ultimately, part of the charm of stick insects is the contrast between appearance and

reality. They seem like background characters in the story of the forest, but once you

learn about their abilities, they become unforgettable. Teachers use them to explain

evolution, artists draw inspiration from their shapes and poses, and bug enthusiasts

appreciate them as living examples of how far natural selection can push a simple idea:

“What if you just looked like a stick?”

Whether you meet them in a rainforest, classroom, or terrarium on someone’s bookshelf,

stick insects have a way of quietly stealing the show. They don’t buzz, roar, or sting.

They simply stand there, perfectly still, embodying one of nature’s most underrated

superpowers: the art of not being noticeduntil you finally do.