Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Table of Contents

- What “Lost Forever” Really Means

- 1) The Library of Alexandria’s Scrolls

- 2) The Amber Room

- 3) The Bamiyan Buddhas

- 4) The Colossus of Rhodes

- 5) The Lighthouse of Alexandria (Pharos)

- 6) The Peking Man Fossils

- 7) The Vanished Maya Codices

- 8) Leonardo’s “Battle of Anghiari”

- 9) Lost Music Masters in the 2008 Universal Fire

- 10) “London After Midnight” and the Era of Lost Films

- What These Losses Teach Us

- of “This Hit Me in the Feelings” Experiences

History isn’t just “what happened.” It’s also what didn’t make it to the presentbecause it burned, sank, crumbled, got looted, or

was accidentally filed under “miscellaneous” (humanity’s most tragic folder).

Below are ten cultural artifactsbooks, buildings, artworks, recordings, and relicswhose original forms are gone for good (or so close to “for good”

that we’d need a miracle, a time machine, or both). Along the way, you’ll see a pattern: the past is fragile, and the present sometimes treats it like a

disposable cup.

Table of Contents

What “Lost Forever” Really Means

“Lost” can mean destroyed, scattered beyond recovery, or missing with no credible path back. Sometimes we have copies, sketches, descriptions, or

reconstructionsuseful, valuable, even beautifulbut not the original object in the original context. And that matters, because originals carry details

that copies can’t: materials, craftsmanship, marginal notes, audio texture, physical scale, even the weird little human mistakes that make history feel

alive.

1) The Library of Alexandria’s Scrolls

The Library of Alexandria became the ultimate symbol of lost knowledge: a vast collection of scrolls gathered in one place, representing centuries of

science, literature, and philosophy. The tragedy isn’t only that texts disappearedit’s that entire branches of thought may have vanished with them.

How it disappeared

Contrary to the “one dramatic bonfire” legend, Alexandria’s collections likely declined through a messy sequence of fires, conflict, political shifts,

and plain old neglect. The result was the same: a cultural hard drive wipe, long before backups were a thing.

Why it still hurts

We can only guess what was lost: complete works of ancient playwrights, early scientific treatises, records of distant cultures, and competing ideas

that might have changed how the modern world developed. The Library’s ghost is basically history whispering, “You sure you didn’t want to save that file?”

2) The Amber Room

Imagine a room lined with amber panels, gold leaf, mirrors, and intricate carvingsso dazzling it was nicknamed the “Eighth Wonder of the World.”

Now imagine it being dismantled, shipped away, and then… simply vanishing.

How it was lost

During World War II, Nazi forces looted the Amber Room from near St. Petersburg and transported it to Königsberg. As the war closed in, it was

crated up againand after that, its trail fades into smoke, rubble, and speculation. Many historians suspect it was destroyed, but the mystery persists.

What we have instead

A painstaking reconstruction now stands at the Catherine Palace. It’s stunningand also a reminder that even the best reconstruction is still a

“best effort” after the original has slipped through history’s fingers.

3) The Bamiyan Buddhas

Carved into Afghanistan’s Bamiyan cliffs around 1,500 years ago, the two monumental Buddha statues weren’t just artthey were proof of a time when

the region sat at a crossroads of cultures, trade, and ideas.

How they were lost

In March 2001, the Taliban destroyed the statues. It wasn’t an accident, and it wasn’t the slow weathering of timeit was a deliberate erasure.

The empty niches left behind are now among the loudest “silences” in cultural heritage.

Why the absence matters

Photos, measurements, and fragments remain, and there are ongoing debates about preservation and possible partial reconstruction. But the originals,

in their original place, are goneand that specific human achievement can’t be re-created from scratch.

4) The Colossus of Rhodes

The Colossus of Rhodesone of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient Worldwas a gigantic statue symbolizing resilience and victory. It also serves as a

cautionary tale: even “wonders” can have surprisingly short lifespans.

How it was lost

An earthquake toppled the statue in the 3rd century BCE. Ancient sources describe it breaking dramatically, and later accounts suggest the remaining

materials were eventually removed and sold as scrap. A wonder of the world, reduced to “recycling.”

What survives

Mostly stories, a few descriptions, and the enduring cultural idea of a giant guardian statueechoed in later art and imagination, even when the

original is long gone.

5) The Lighthouse of Alexandria (Pharos)

Another of the Seven Wonders, the Pharos lighthouse guided ships into Alexandria’s harbor and helped define what a major coastal city could be:

practical, wealthy, and architecturally bold.

How it was lost

Over centuries, earthquakes damaged the structure until it became a ruin. Eventually, remaining stone was reused in later constructionhistory’s

most literal “repurposed content.” The lighthouse didn’t just vanish; it was absorbed into the city’s next chapter.

Why it’s still priceless

We can model it, excavate underwater blocks, and write about it, but standing at its basewatching a beacon blaze over the Mediterraneanis an

experience we can’t truly get back.

6) The Peking Man Fossils

The “Peking Man” fossilsHomo erectus remains discovered near Zhoukoudianwere among the most important paleoanthropological finds of the 20th century.

Then they disappeared, like a detective story written by chaos.

How they were lost

In 1941, during wartime upheaval, plans were made to move the fossils for safekeeping. They never reached their destination. Despite investigations and

theories, the original fossils remain missing.

What we still have

Detailed study notes, casts, photographs, and scientific descriptions preserve some knowledge. But the originals matteredand still matterbecause new

techniques can extract fresh information from old bones. Unless the fossils reappear, that door stays mostly closed.

7) The Vanished Maya Codices

The Maya wrote screenfold “books” filled with astronomy, calendars, rituals, and history. Today, only a tiny handful survive. The rest were destroyed in

the colonial eraan information loss so huge it’s hard to even picture.

How they were lost

In the 1500s, Spanish clergy targeted Indigenous texts as “heretical,” burning large numbers of Maya books. The destruction wasn’t just cultural; it was

intellectualan intentional interruption of how a civilization recorded itself.

Why this one is especially brutal

Because we know what books can contain: voices, jokes, daily life, observations of the sky, arguments, doubts. When most of those books are burned,

a civilization becomes easier to misunderstandand harder to hear.

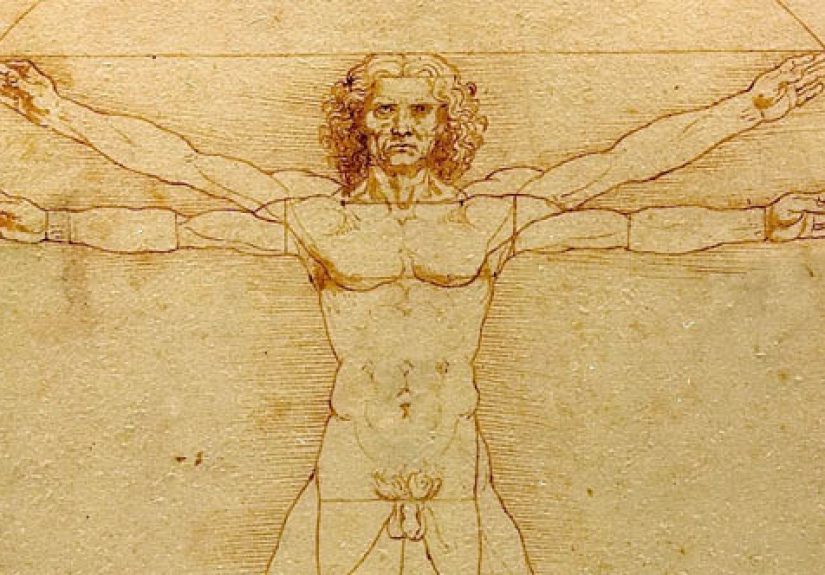

8) Leonardo’s “Battle of Anghiari”

Leonardo da Vinci was commissioned to paint a monumental battle scene in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio. Preparatory drawings suggest it would have been a

masterpiece of motion, expression, and raw intensity. Instead, it became one of art history’s biggest “what ifs.”

How it was lost

The work was never completed, and later renovations in the hall complicate the story. Some researchers have argued fragments might exist behind a

later wall; others think the painting never reached a stage that could survive. Either way, the finished Leonardo mural people hoped for doesn’t exist

in public view.

What survives

Studies, copies, and echoes in later artists’ workenough to appreciate the idea, but not enough to experience the real thing as Leonardo intended it.

9) Lost Music Masters in the 2008 Universal Fire

Cultural artifacts aren’t only ancient. Sometimes they’re magnetic tape in a vaultquietly holding the original “first generation” sound of iconic

recordings. In 2008, a fire at Universal Studios Hollywood became a modern preservation nightmare.

What was lost (and why it matters)

Investigations and reporting later alleged that vast numbers of master recordings were destroyedmaterials that can’t be perfectly replaced by commercial

copies. Even when music remains available, masters matter for future remastering, restoration, and historical accuracy. It’s the difference between

“a photo of a painting” and “the painting itself.”

The modern twist

This loss also highlights a modern problem: we create enormous cultural output, but we often store it in ways that assume nothing will ever go wrong

which is a bold strategy in a world with fire, floods, and human error.

10) “London After Midnight” and the Era of Lost Films

“London After Midnight” (starring Lon Chaney) is one of the most famous lost silent films. It’s also a stand-in for a bigger tragedy: early cinema was

treated as disposable, and film stock itself was dangerously fragile.

How it was lost

The last known print was reportedly destroyed in an MGM vault fire in the mid-1960s. That one event is linked to the disappearance of many early works,

turning “movie history” into “movie mystery.”

Why it counts as a cultural artifact

A lost film isn’t just missing entertainment. It’s missing performance styles, set design, pacing, and storytelling choicesevidence of how people once

imagined fear, romance, humor, and modern life. When a film disappears, so does a piece of the culture that made it.

What These Losses Teach Us

The uncomfortable truth is that cultural loss isn’t rareit’s normal. What’s rare is preservation done well: multiple copies, careful storage, clear

ownership, and serious funding. If these stories have a shared moral, it’s this:

- Redundancy saves culture: one vault, one server, one building is a single point of failure.

- Documentation matters: photos, scans, casts, inventories, and research notes can be the difference between “gone” and “understood.”

- Transparency matters: cover-ups and vague records slow recovery and weaken trust.

- Respect matters: the most devastating losses are often intentional, fueled by the idea that some histories don’t deserve to exist.

Preserving cultural heritage isn’t nostalgia. It’s a public servicelike keeping the lights on, except the lights illuminate who we are and where we came from.

of “This Hit Me in the Feelings” Experiences

Reading about lost artifacts is a strange emotional cocktail. Part awe, part grief, part “how did nobody label the box?” The feeling usually starts

small: you see a photo of an empty niche where the Bamiyan Buddhas once stood, or you hear a snippet about the Library of Alexandria, and your brain

tries to fill in the missing pieces like it’s completing a puzzle with half the pieces eaten by a history-loving raccoon.

One of the most vivid “experience” moments people have with cultural loss happens in museumsespecially when the display label quietly admits, “Original

destroyed” or “Known only from copies.” You can stand in front of a reconstruction and still feel the gap. It’s not that reconstructions aren’t impressive;

they can be breathtaking. It’s that the mind knows there’s a missing handshake across time. The original object had a direct connection to the person who

made it and the world that used it, and that connection is exactly what’s been severed.

Another experience is the deep-dive spiral. You start with “What was the Amber Room?” and suddenly it’s 2:00 a.m. and you’re reading about wartime

evacuations, shipping routes, crated panels, and rumors that sound like they were invented by a novelist who drank three espressos and then shouted,

“Plot twist!” Even when you’re trying to be practical and skeptical, the human mind loves a mysteryespecially one where the stakes are beauty, memory,

and a sense of justice.

The modern losses can feel even weirder, because they’re so relatable. Ancient scrolls burning is heartbreaking, but also distant. A vault of master

recordings going up in smoke? That feels like someone deleting your entire photo libraryexcept the photos belong to whole generations. It also forces

you to notice how flimsy “forever” can be. We assume digital copies and corporate archives equal safety. But preservation isn’t a vibe. It’s a plan.

If you want a more hopeful experience, try “reverse grief”: seek out what did survive. Look up the surviving Maya codices. Read how researchers

use casts and notes to keep Peking Man scientifically alive, even without the originals. Explore how underwater archaeology can recover pieces of the

Pharos lighthouse and translate them into digital reconstructions. You start to feel something like gratitudemixed with a new kind of vigilance.

Because the emotional punch of these stories isn’t only sadness. It’s motivation: to back things up, to fund libraries and archives, to support museums,

and to treat culture like the nonrenewable resource it often is.