Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- 1) Psycho (1960): Hitchcock’s “Fine, I’ll Do It Myself” Power Move

- 2) Star Wars (1977): The Best Paperwork Deal in the Galaxy

- 3) Rocky (1976): The Script With a Built-In “No, Seriously” Clause

- 4) Apocalypse Now (1979): Financing a Masterpiece Like a High-Stakes Jenga Tower

- 5) The Blair Witch Project (1999): The Internet Myth That Sold Tickets

- What These “Insane Schemes” Teach Us About Classic Movies

- of Experiences: Falling Down the “How Was This Even Made?” Rabbit Hole

- Conclusion

Every classic movie has a behind-the-scenes story. Some have two: the one in the script, and the one that happened in

boardrooms, backlots, and very nervous phone calls with people holding checkbooks.

Hollywood history isn’t just “lights, camera, action”it’s also “rights, contracts, and wait, you did what to fund this?”

In this list, “insane schemes” doesn’t mean anything shady. It means the kind of bold, borderline-unreasonable

plan that makes you wonder how the movie industry functions at alland then makes you grateful it does, because we

got some of the most iconic films ever made.

These are five classic movies that were made possible by clever deals, risky bets, and marketing moves so audacious

they’d get your group chat typing in all caps. Along the way, we’ll pull out lessons for creators, film fans, and anyone

who’s ever tried to negotiate anything more intense than who picks the next movie night selection.

1) Psycho (1960): Hitchcock’s “Fine, I’ll Do It Myself” Power Move

Alfred Hitchcock wasn’t exactly an unknown quantity by 1960. But even he had projects studios didn’t want to touchat

least not with their normal budgets and normal expectations. So Hitchcock made an offer that basically translated to:

“Let me do it my way, and I’ll bet my own money and reputation that it works.”

The scheme: trade a typical paycheck for ownership

Instead of taking a standard director’s fee, Hitchcock structured a deal that gave him a major ownership stake in the film.

That’s not just a “nice bonus.” That’s a “this movie becomes a personal investment portfolio” level of confidence.

It’s the kind of business maneuver that feels like flipping the chessboard… and somehow still winning.

The scheme inside the scheme: make “cheap” look intentional

Psycho famously leaned into choices that looked like limitations: a tight schedule, a controlled production, and the kind of

stripped-down intensity that makes every hallway feel like it has opinions about you.

The genius part is that the lean approach didn’t read as “we’re saving money.” It read as “we’re creating a mood.”

That’s the difference between a budget and a style.

Why it worked

Hitchcock’s gamble didn’t just create a hitit rewired what audiences expected from suspense movies and what studios were willing

to gamble on. The broader lesson for film history is simple: sometimes the “insane scheme” is refusing to accept

the normal rules of how creative work gets financed, marketed, and packaged.

- Hollywood lesson: ownership can matter more than upfront cash.

- Creative lesson: limitations become iconic when you turn them into choices.

2) Star Wars (1977): The Best Paperwork Deal in the Galaxy

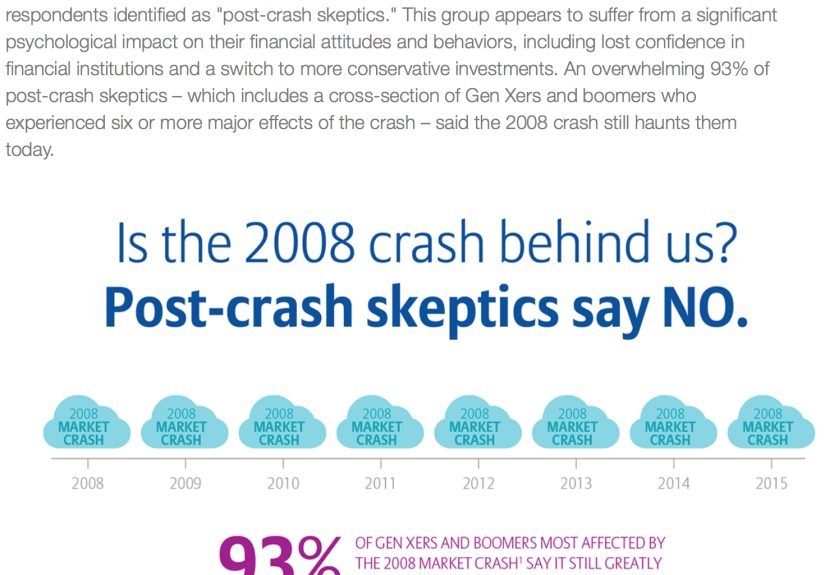

Today, “Star Wars merchandise” is basically its own form of currency. But in the mid-1970s, licensing and merchandising

weren’t the unstoppable machine they are now. Which is exactly why George Lucas was able to pull off a deal that

sounds like a Hollywood urban legend… except it’s real.

The scheme: accept less money now to control the future

Lucas had enough leverage to renegotiate his directing fee upward. Instead, he made a trade: keep the fee lower, but

retain key rightsespecially licensing/merchandising and sequel control. On paper, a studio could view that as “fine,

take the weird toy stuff.” In reality, it was a master key to an empire.

The hidden genius: protecting sequels before anyone believed in them

Studios weren’t betting on sequels the way they do now. A space fantasy with unfamiliar characters and ambitious effects

felt risky. But by thinking beyond a single film, Lucas treated the project like a long-term world rather than a

one-time event. That long view helped define modern blockbuster strategy.

Why it worked

Star Wars didn’t just become a hit; it became a template. The scheme wasn’t a gimmickit was a structural advantage.

It gave Lucas creative and financial control that most filmmakers simply don’t get, and it helped prove that

“ancillary rights” can be the real main character.

- Hollywood lesson: the scariest contract clause is the one you ignore.

- Fan lesson: the toys weren’t an afterthought; they were part of the strategy.

3) Rocky (1976): The Script With a Built-In “No, Seriously” Clause

If you’ve ever watched Rocky and felt your motivation level rise by 300%, the behind-the-scenes story basically does the same thing.

Before the film became an underdog legend, it was a negotiation standoff starring the same underdog… in real life.

The scheme: refuse the big check unless you get the big role

Sylvester Stallone wrote the screenplay and got offers to sell it. The catch: studios wanted the story, but they didn’t necessarily

want him as the lead. Stallone’s move was simple and terrifying: he refused to sell unless he could star.

Imagine being offered life-changing money and saying, “No thanks, I’m betting on me.”

The pressure tactic: make the dream non-transferable

This is what makes it a scheme (the good kind): Stallone made the project’s identity inseparable from his participation.

The script wasn’t just a product; it was a package deal. If the studio wanted the emotional authenticity of the underdog,

it had to come with the guy who wrote it with that exact perspective.

Why it worked

The studio eventually went for it, even if it meant compromises and a lower budget than a flashier production might get.

But those constraints helped the movie feel grounded, hungry, and realexactly the emotional flavor that turned it into a classic.

- Hollywood lesson: sometimes the strongest leverage is “I can walk away.”

- Human lesson: betting on yourself is dramatic… and occasionally Oscar-winning.

4) Apocalypse Now (1979): Financing a Masterpiece Like a High-Stakes Jenga Tower

Apocalypse Now has a reputation for being one of the most notoriously difficult productions in film historyand not just because it aimed

for epic scale. It also had to solve a simple but brutal problem: how do you fund a movie that keeps getting bigger, harder,

and more complicated while it’s happening?

The scheme: secure distribution money and build the rest around it

One key piece was a distribution arrangement that brought significant funding up front, essentially using the promise of the finished movie

as collateral for the movie’s ability to exist in the first place. It’s the filmmaking version of building the plane while flying it

and also writing the flight manual midair.

The creative risk: treat logistics like part of the art

A production this ambitious forces decisions where art and business are welded together. Every day of shooting can reshape the budget,

the schedule, and the final cut. Yet the film’s intensity is partly powered by that very pressure: it feels like a movie made at

the edge of what’s controllable, because in many ways, it was.

Why it worked

Even with chaos and uncertainty, the film emerged as a landmarkproof that “impossible” productions sometimes become the most influential,

especially when a director refuses to reduce the vision to fit a safer template. The scheme wasn’t about trickery.

It was about making the financial structure flexible enough to support something enormous.

- Hollywood lesson: distribution can be a funding tool, not just a release plan.

- Creative lesson: the toughest productions often leave the deepest fingerprints on cinema history.

5) The Blair Witch Project (1999): The Internet Myth That Sold Tickets

If you want a masterclass in marketing, The Blair Witch Project is basically required readingexcept it wasn’t a book, it was a website,

a rumor, and a straight-faced commitment to “what if the audience isn’t sure what’s real?”

The scheme: build a story outside the movie

The campaign didn’t just promote a film; it constructed a legend around it. By using early web storytelling, “found” materials,

and a tone that mimicked real investigation, the marketing helped create the sensation that the film wasn’t simply fiction.

(To be clear: it was fiction. But it was marketed like a mystery you were invited to solve.)

The budget trick: make limitations feel like evidence

A traditional horror film often spends money to show you the monster. Blair Witch did the opposite: it used what it couldn’t show

as part of the fear. The minimalism wasn’t just cost-saving; it became the aesthetic. And because the marketing framed the

story as “maybe real,” audiences didn’t walk in looking for polished spectaclethey walked in looking for clues.

Why it worked

This is one of the clearest examples of an “insane scheme” creating a new lane in Hollywood. The film’s success helped popularize

the idea that a smart narrative frame and a strategic marketing story can multiply a modest production into a cultural event.

- Hollywood lesson: marketing can be worldbuilding.

- Viewer lesson: if a movie makes you argue afterward, it already won.

What These “Insane Schemes” Teach Us About Classic Movies

Put these five films side by side and a pattern pops out: the “scheme” is rarely about cutting corners. It’s about changing the terms.

Instead of asking, “How do I get permission?” these creators asked, “How do I structure this so it can’t be ignored?”

Recurring tactics that keep showing up

- Ownership plays: trading upfront money for long-term control (Psycho, Star Wars).

- Identity leverage: making the project inseparable from the creator (Rocky).

- Flexible financing: building funding around distribution and future value (Apocalypse Now).

- Story-first marketing: turning promotion into part of the experience (Blair Witch).

The biggest takeaway for film fans is that “classic” doesn’t automatically mean “smoothly produced.”

Sometimes “classic” means “a miracle that survived spreadsheets.”

of Experiences: Falling Down the “How Was This Even Made?” Rabbit Hole

There’s a specific kind of joy that hits when you watch a classic movie and then learn the behind-the-scenes story. It’s like

discovering your favorite dessert also survived a dramatic kitchen meltdown and a missing ingredient crisissuddenly it tastes even better,

because it shouldn’t exist, and yet it does.

Film fans often have a “first time” moment with this: you finish Psycho and realize the tension feels engineered, then you learn Hitchcock

engineered the business side too. Or you rewatch Star Wars and notice how confident the world feels, then you read about Lucas prioritizing sequel

and merchandising rights like he was quietly planning the next four decades. The movie becomes two stories at oncethe story on screen and the story

of how the screen got paid for.

These production schemes also change the way you talk about the films with other people. Instead of debating only characters and plot, you start debating

decisions: “Would you have taken the big money and let a star play Rocky?” “Would you have traded your salary for merchandising rights if everyone told

you the movie might flop?” “Would you have had the guts to bet your reputation on a lean, risky thriller when the safer move was making the studio happy?”

Suddenly movie night turns into a masterclass in negotiation and creative courage.

And honestly, it can be comfortingespecially if you create anything, whether it’s videos, a blog, music, or even school projects. The myth of art is

that masterpieces appear fully formed when genius strikes. The reality is messier and more relatable: people make plans, get rejected, pivot, bargain, improvise,

and sometimes build an entire strategy out of “Well, I guess we’re doing it this way now.” That’s not a flaw in the process. It is the process.

The most fun part is noticing how each scheme matches the final vibe of the movie. Rocky feels hungry because it was born out of hunger.

Blair Witch feels like a rumor because it was marketed like one. Apocalypse Now feels intense and uncontainable because the production itself

flirted with being uncontainable. When the behind-the-scenes strategy lines up with the on-screen tone, it’s hard not to admire the whole thing as one big,

wild act of storytellingcontracts included.

So the next time you watch a “classic,” try the double-feature experience: the film itself, plus the story of how it got made. You’ll laugh, you’ll gasp,

and you’ll probably say, at least once, “There is no way this would get approved today.” Which is exactly why it’s worth celebrating.

Conclusion

Classic movies aren’t just remembered because they’re goodthey’re remembered because they’re bold. Sometimes that boldness shows up in a plot twist,

sometimes in a groundbreaking special effect, and sometimes in a contract clause that quietly reshapes Hollywood.

From Hitchcock’s ownership gamble to Lucas’s rights play, from Stallone’s stubborn insistence to the flexible financing of an epic production,

and finally to an internet-era marketing myth that turned a tiny film into a phenomenonthese insane schemes didn’t just enable the movies.

They helped define what “classic” can mean: a creative risk that pays off so hard it becomes legend.