Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What a KIM-1 Really Is (and Why Memory Is the Whole Show)

- How Memory Problems Show Up on a KIM-1

- Start With the Boring Stuff: Power, Ground, and Timing

- The Classic Trick: Piggyback Testing (Fast, Reversible, and Surprisingly Effective)

- When the “Fix” Makes It Worse: The Hidden Cost of Rework on Old Boards

- The Plot Twist: Shorts, Bridges, and “It Was Never the RAM” Moments

- How You Confirm the Memory Problem Is Truly Resolved

- Preventing the Next Memory Scare

- Conclusion and Real-World Experiences: The Human Side of Fixing a KIM-1

Every retrocomputer has a personality. Some are charming. Some are stubborn. And some (looking at you, vintage single-board trainers)

are basically a mystery novel written in oxidation, marginal voltages, and “how did that solder get there?”

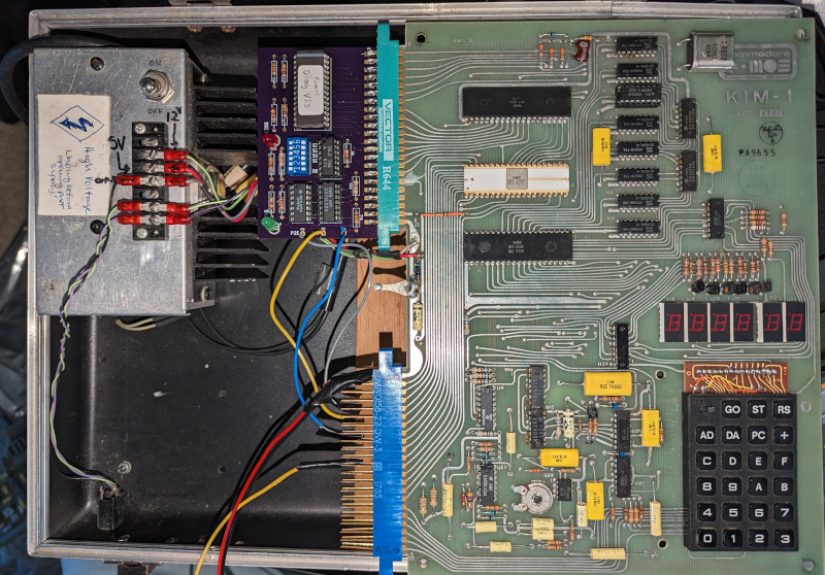

The MOS Technology KIM-1 is famous for being small, approachable, and wildly influentialan early 6502-based computer module with a keypad,

LED display, and just enough memory to teach a generation how computers actually think. But when a KIM-1 develops a memory problem,

it can feel like your 1976 time machine suddenly got stage fright.

This article breaks down what “KIM-1 memory problems” look like, why they happen, and how hobbyists typically track them downending with a

satisfying (and very real) kind of ending: the memory problem resolved, the monitor stable, and the board back to doing what it was born to do.

What a KIM-1 Really Is (and Why Memory Is the Whole Show)

The KIM-1 (short for Keyboard Input Monitor) was designed so engineers and hobbyists could experiment with the MOS 6502.

It wasn’t trying to be a sleek “appliance computer.” It was a learning platform: CPU, ROM monitor, RAM, I/O, and expansion connectors,

all on one board. If you could read hex, you could make it dance.

And that’s the catch: everything depends on memory behaving. The KIM-1’s onboard RAM is modest by modern standards, but it’s foundational:

it holds your data, your small programs, and the working space the system needs to keep the monitor responsive.

When RAM misbehaveseven a single stuck bityou don’t just get “a bug.” You get chaos in the most literal, electrical sense.

The KIM-1 memory map, simplified

The 6502 can address 64 KB total, but the KIM-1’s key built-in regions live in the low 8 KB, decoded into 1 KB “blocks.”

The board’s monitor ROM lives in two 1 KB chunks (often referenced as the 6530-002 and 6530-003 ROM areas), while the lowest 1 KB

(addresses 0000–03FF) is the onboard static RAM. Other parts of the low-memory region are reserved for I/O, timers,

and (optionally) expansion.

Practical takeaway: if the KIM-1 can’t reliably read and write that base RAM, nearly everything else becomes harder to trustbecause the

machine’s ability to run tests, accept input, and display consistent results is built on that shaky foundation.

How Memory Problems Show Up on a KIM-1

A modern laptop with bad memory might crash politely. A KIM-1 with bad memory tends to fail like a dramatic actor: unpredictably and

with flair. Symptoms often include:

- Intermittent failures (works cold, fails warm; fails after a bump; fails only sometimes).

- Weird monitor behavior (unexpected values, inconsistent reads, “phantom” changes).

- Unreliable keypad/display responses that look like a logic problem but are actually bad RAM writes.

- Memory test patterns that indicate one chip/bit line is failing (especially when RAM is split across multiple devices).

One reason KIM-1 troubleshooting can be confusing is that a “memory-looking” symptom isn’t always caused by the memory chip itself.

The RAM can be fine, but the signal getting to itor back from itcan be compromised by sockets, solder joints, bus buffers,

shorts, or timing/power issues.

Start With the Boring Stuff: Power, Ground, and Timing

Retro repair wisdom: dramatic problems often have unglamorous causes. Before blaming a RAM chip, restorers usually verify three basics:

power rails, grounding integrity, and stable timing/clock behavior.

Why power problems mimic memory problems

Static RAM and TTL-era logic can get flaky when voltage is low, noisy, or droops under load. A KIM-1 may “sort of” run but fail tests,

corrupt values, or behave inconsistently. That looks like memory failureuntil you measure the rails and discover the board is basically

running on hope and ripple.

A good approach is methodical: confirm regulated supply behavior, check for heat-stressed parts, and make sure your ground path is solid.

If you’re restoring hardware, basic safety matters tooESD precautions and careful probing save both parts and sanity.

The Classic Trick: Piggyback Testing (Fast, Reversible, and Surprisingly Effective)

When a specific RAM chip is suspected, one of the quickest “no-commitment” tests is piggybacking: placing a known-good SRAM chip on top of

the suspected one so their pins make contact. If the system suddenly behaves, you’ve gained strong evidence that the original chip (or its

connection) is the problem.

This works best when the failure is in the RAM device itself (or a marginal internal connection). It’s not guaranteedsome faults are too

complex, and some bus conflicts make results ambiguousbut as a first-pass diagnostic, it can be incredibly revealing.

If piggybacking improves behavior, the next step is usually to replace the RAM chip properlyideally with a socket installed so future

troubleshooting doesn’t require repeated solder rework. Of course, vintage boards don’t always make this easy.

When the “Fix” Makes It Worse: The Hidden Cost of Rework on Old Boards

Here’s the part nobody posts about until it happens: removing a chip from a decades-old board can create brand-new problems.

Older PCBs may have fragile pads, thin plating, and traces that lift if overheated or stressed.

That’s why many restorers treat chip removal like surgery: controlled heat, patience, and a plan for repair if something lifts.

Sometimes a lifted trace can be repaired with conductive ink or careful jumper wiring. Sometimes a repair “works” but introduces

marginal conductivity that fails again later.

In the well-known KIM-1 memory repair story that inspired this article’s title, the suspected RAM at the schematic’s U10 position

tested “guilty” via piggybacking. But after removal and repair attempts, the system still wasn’t rightleading to the true culprit:

not the chip, but a problem introduced during rework.

The Plot Twist: Shorts, Bridges, and “It Was Never the RAM” Moments

A KIM-1 board can fail memory tests for reasons that have nothing to do with silicon defects. Common non-RAM culprits include:

- Solder bridges between adjacent pins (especially on tight, older layouts without modern solder mask behavior).

- Cracked joints that look fine but go open-circuit with temperature or vibration.

- Socket oxidation (if socketed) causing intermittent bit failures.

- Bus/buffer issues where RAM is fine but data lines are corrupted in transit.

- Dirty edge connectors and poor contact on expansion interfaces that feed noise back into the system.

In that same repair saga, the “spoiler” ending was wonderfully human: after chasing chips and repairing traces,

the problem came down to a solder bridgean accidental short that made the memory subsystem behave like it was haunted.

Remove the short, and the KIM-1 snaps back into a stable, predictable machine.

This is why experienced troubleshooters lean on structured diagnostics. If you only swap parts, you might eventually get lucky.

If you measure, isolate, and verify, you get something better than luck: confidence.

How You Confirm the Memory Problem Is Truly Resolved

The goal isn’t just “it boots once.” The goal is repeatability: cold start, warm start, multiple test passes, and stable read/write behavior

across the entire RAM range you expect to use.

Use tests that catch real-world failures

Simple “fill memory with a value and read it back” tests are a good startbut not always enough.

Some memory failures only appear with specific patterns (walking bits), address interactions (one write affects another address),

or page-aligned faults that basic tests can miss.

Many hobbyists keep a small library of classic tests designed for 6502-era systems: walking ones and zeros, alternating patterns,

and tests that avoid “nice” alignments that can accidentally hide a fault. The best tests are the ones that make failures obvious,

repeatable, and localizable.

Validate the “whole chain,” not just the chip

If a fault was caused by a solder bridge or a marginal trace, the fix should be validated beyond the memory IC:

confirm the affected data line(s) are clean, that adjacent pins are not shorted, and that the board behaves the same after being

gently moved, warmed, and re-powered. Intermittent faults love to play dead during your first victory lap.

Preventing the Next Memory Scare

Once your KIM-1 is stable, the best repair is the one you don’t have to repeat. A few practical habits (kept non-destructive and reversible

when possible) can reduce future “why is it doing that again?” moments:

- Socket strategic chips if appropriate, using quality sockets and clean soldering techniques.

- Clean connectors (edge connectors and headers) to reduce contact resistance and noise.

- Use solid regulated power with clean groundingavoid questionable supplies that droop under load.

- Watch heat: thermal stress can turn “fine” into “flaky” over time.

- Document changes: keep notes so future-you isn’t forced to reverse-engineer your present-you.

Also, it’s worth acknowledging the collector angle: original parts can be valuable and historically interesting.

When possible, restorers often preserve removed components, label them, and keep modifications tidy and reversible.

A careful repair can respect both function and history.

Conclusion and Real-World Experiences: The Human Side of Fixing a KIM-1

“Memory problem resolved” sounds like a clean, clinical statementlike a checkbox on a lab report. In real life, it’s usually a small

adventure. And if you’ve never repaired a KIM-1 (or any 6502-era board), the stories people tell all rhyme in the same way:

start confident, get humbled, learn something, and finish proud.

One common experience is the emotional roller coaster of intermittent faults. The board boots once and you’re ready to frame

it as art. Then it fails on the next reset and you’re staring at the LEDs like they personally betrayed you.

This is where KIM-1 troubleshooting teaches the best lesson in electronics: don’t argue with resultsreproduce them.

Hobbyists learn to run tests multiple times, from cold start to warmed-up operation, and to log exactly what changed.

That shift from “hoping” to “verifying” is often the moment someone stops being a casual collector and becomes a confident restorer.

Another shared experience is discovering how much “the board” is more than “the chips.” People go in expecting a bad RAM IC and come out

understanding sockets, solder joints, signal integrity, and the realities of older PCB construction.

Even a straightforward fixlike replacing an SRAMoften turns into a mini-course in rework discipline:

how easily pads can lift, how a repaired trace can be electrically “okay” but mechanically fragile, and how a tiny solder bridge can mimic

catastrophic silicon failure. Many restorers eventually adopt a rule: before you blame a chip, look for a short; before you celebrate,

look for the short you created while fixing the first short.

The KIM-1 community experience matters too. People swap schematics, compare address maps, and share “this exact symptom was a bad data line”

war stories. Someone posts a test pattern interpretation, someone else points out a common buffer IC failure, and suddenly a repair that felt

impossible becomes a checklist. That collective knowledge is why a 1970s training computer can still be repaired in the 2020s without

needing a corporate service department.

Finally, there’s the most satisfying experience of all: the moment the machine becomes boringly correct. The keypad responds.

Memory values stay put. Tests pass repeatedly. The board doesn’t care if you reset it ten times in a row.

That “boring” stability is the real winbecause it means you didn’t just get lucky. You actually solved the problem.

And when a KIM-1’s memory is stable again, it stops being a fragile artifact and turns back into what it has always been:

a friendly, hands-on gateway into how 6502 computers workone hex byte at a time.