Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Use a Stethoscope to Check Your Pulse?

- What You’ll Need

- The Two Pulse Options You Can Hear with a Stethoscope

- How to Take Your Own Pulse with a Stethoscope in 10 Easy Steps

- Troubleshooting: When You Can’t Hear Anything (or It Sounds Like a Tiny Thunderstorm)

- What’s a “Normal” Resting Heart Rate?

- When to Call a Healthcare Professional

- Bonus Tips for Better Accuracy

- Common Questions People Ask (Usually After They Try It Once)

- Experience Notes: What It’s Like the First Few Times You Do This (And Why That’s Normal)

- Conclusion

Checking your pulse is one of those “adulting” skills that feels suspiciously like something you should’ve learned

in middle schoolright between “how taxes work” and “why your phone battery dies at 37%.”

The good news: you don’t need a medical degree to measure your heart rate at home. And if you have a stethoscope,

you can get an especially accurate read by listening directly to your heart (hello, apical pulse).

In this guide, you’ll learn exactly how to take your own pulse with a stethoscope in 10 easy stepsplus how to

calculate beats per minute, what “lub-dub” actually means, and what to do when your heartbeat decides to go

freestyle. We’ll also cover common mistakes, troubleshooting, and when it’s time to call a healthcare professional.

Why Use a Stethoscope to Check Your Pulse?

Most people check pulse at the wrist or neck with their fingers. That works great. But using a stethoscope can be

helpful when:

- You want a more direct measurement by listening to the heart itself (the “apical pulse”).

- Your wrist pulse is hard to feel (cold hands, anatomy differences, or you’re pressing too hard).

- Your rhythm seems irregular and you need to count for a full minute.

- You’re practicing a health skill for caregiving, school, EMT training, or general peace of mind.

Quick note: a stethoscope won’t diagnose heart conditions. It’s a tool for measurement and awareness.

If anything feels “off” (especially with symptoms like chest pain, fainting, or shortness of breath), don’t play heroget medical help.

What You’ll Need

- A stethoscope (basic is fineno need for a luxury model unless you enjoy premium “whoosh” sounds).

- A watch/phone timer with seconds.

- A quiet spot (fans, TVs, and chatty pets are the enemies of auscultation).

- A notebook or notes app if you want to track your readings over time.

The Two Pulse Options You Can Hear with a Stethoscope

1) Apical pulse (recommended)

This is the heart rate you hear over the chest near the heart’s apex. It’s often considered the most accurate way to measure

rate and rhythm because you’re listening to the heart’s actual beat rather than a pulse wave in an artery.

2) Arterial pulse sounds (optional)

You can sometimes hear pulse sounds over an artery (like the wrist), but it’s usually easier and more reliable to use your fingers there.

If you’re using a stethoscope, the chest method is typically the main event.

How to Take Your Own Pulse with a Stethoscope in 10 Easy Steps

-

Get into the right position.

Sit comfortably or lie down. If you’re checking a resting heart rate, give yourself a minute to relax.

If possible, avoid measuring right after caffeine, exercise, or a jump-scare from your email inbox. -

Make your environment quieter than your group chat at 2 a.m.

Turn down background noise. Even small sounds (air conditioning, clothing rustle, tapping fingers) can make heart sounds harder to hear.

-

Put the earpieces in correctly.

Stethoscope eartips should point slightly forward (toward your nose), following the direction of your ear canals.

If it feels weird or muffled, flip them and try again. -

Warm the chest piece (yes, really).

Hold the diaphragm (the flat side) in your hand for 5–10 seconds so it’s not ice-cold on your skin.

Your body tenses when startled, and your heartbeat will not appreciate the drama. -

Find the apical pulse location on your chest.

For most adults, the apical pulse is heard around the left side of the chest near the

5th intercostal space along the midclavicular line.

Translation: start at your collarbone, move down a few rib spaces, and aim slightly left of center.

Anatomy varies, so think “general neighborhood,” not “GPS coordinates.”Tip: if you’re struggling, try lying slightly turned to your left. This can bring the heart closer to the chest wall and make sounds easier to hear.

-

Place the diaphragm on bare skin and apply gentle pressure.

Put the flat diaphragm directly on your skin (not over thick clothing). Press just enough to create a good seal.

Too light = scratchy noise. Too hard = you may add extra rubbing sounds. -

Listen for the “lub-dub” and count beats correctly.

You’ll typically hear two main heart sounds: lub and dub.

Together, “lub-dub” counts as one heartbeat.

Your goal is to count how many complete beats occur in a set time. -

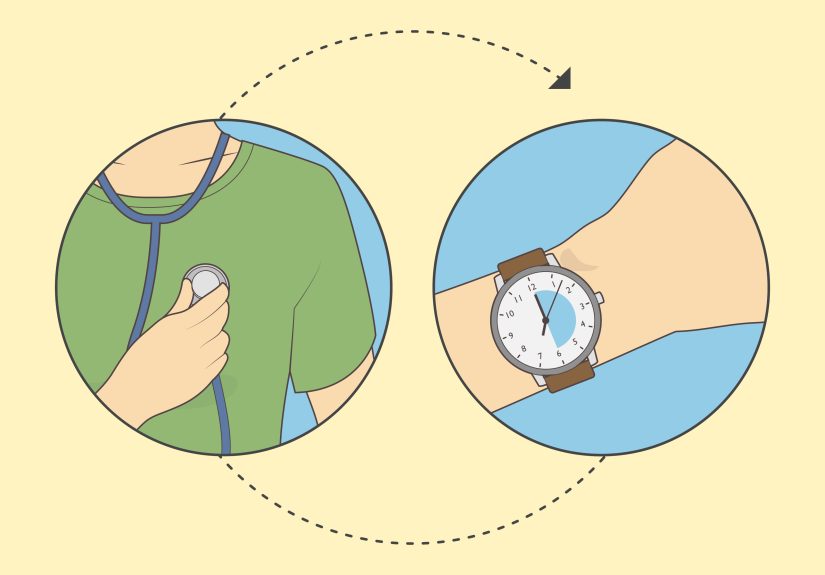

Count for 30 seconds (or 60 seconds if irregular).

If your rhythm sounds steady, count beats for 30 seconds and multiply by 2 to get beats per minute (BPM).

If the rhythm sounds irregular, or you’re checking because of symptoms or heart-related medications,

count for a full 60 seconds for best accuracy. -

Do the math (quick examples).

Here are simple ways to calculate BPM:

- 30 seconds × 2: You count 36 beats in 30 seconds → 36 × 2 = 72 BPM.

- 15 seconds × 4: You count 18 beats in 15 seconds → 18 × 4 = 72 BPM.

- 60 seconds: You count 72 beats in 60 seconds → 72 BPM (no multiplication needed).

If you lose count, don’t panic. Restart. Even clinicians redo counts. Your heart will forgive you.

-

Write it down and clean your stethoscope.

Record the number, the time of day, and what you were doing right before (resting, stressed, post-workout, etc.).

Then wipe the diaphragm and earpieces with an alcohol-based disinfecting wipe and let it dry.

Troubleshooting: When You Can’t Hear Anything (or It Sounds Like a Tiny Thunderstorm)

Problem: “All I hear is whooshing.”

- Check that the diaphragm is on bare skin, not clothing.

- Reduce rubbing: hold the tubing still and avoid touching the chest piece while counting.

- Try a quieter room (fans and open windows are surprisingly loud through a stethoscope).

Problem: “It’s faint, like my heart is whispering.”

- Shift the chest piece slightlysometimes moving half an inch makes a huge difference.

- Lie slightly on your left side to bring the apex closer to the chest wall.

- Make sure the stethoscope is “on” the diaphragm side if yours has a switchable chest piece.

Problem: “I hear extra beats… or weird pauses.”

- Count for a full 60 seconds and note whether it feels irregular or just occasionally “off.”

- Re-check when you’re calm. Stress and stimulants can make rhythm feel jumpy.

- If irregular rhythm is frequent or you have symptoms, contact a healthcare professional.

What’s a “Normal” Resting Heart Rate?

For many adults, a resting heart rate often falls in the 60–100 BPM range when you’re calm, sitting or lying down,

and not sick. Some very fit people may run lower than that without any problem. What matters most is your

baseline (your usual range) and whether you have symptoms.

Your heart rate can change based on sleep, stress, hydration, fever, medications, fitness level, temperature, and even body position.

So if you measure twice and get slightly different numbers, that’s not your heart “lying.” That’s your body being a body.

When to Call a Healthcare Professional

Get medical advice (urgent or emergency, depending on severity) if you notice:

- Chest pain, severe shortness of breath, fainting, or feeling like you might pass out.

- A resting heart rate that is consistently very high or very low for you, especially with symptoms.

- New or frequent irregular rhythm that doesn’t resolve with rest.

- Any situation where you feel “this is not normal for me,” and your gut alarm won’t shut off.

If you’re ever unsure and symptoms are intense, seek emergency care. Measuring your pulse is useful information,

but it’s not a substitute for evaluation when something feels seriously wrong.

Bonus Tips for Better Accuracy

- Measure at the same time daily (like mornings before coffee) if you’re tracking trends.

- Repeat 2–3 times and average the results if you want a steadier number.

- Use a full minute when rhythm is irregular or you’re monitoring a medical issue.

- Stay consistent with posture (sitting vs. lying) when comparing readings over time.

Common Questions People Ask (Usually After They Try It Once)

“Should I use the bell or the diaphragm?”

For basic heart rate counting, the diaphragm is usually the easiest starting point.

If your stethoscope has a tunable diaphragm, pressure changes can emphasize different frequencies. When in doubt, start with the diaphragm and focus on clear “lub-dub.”

“Can I take my pulse through clothing?”

You can try, but accuracy usually improves on bare skin. Fabric adds friction noise and dulls the sound.

If modesty or comfort is a concern, thin clothing is better than thick hoodies (your heart is not a podcast; it needs less “soundproofing,” not more).

“What if I can’t find the apical pulse spot?”

That’s common. Bodies vary. Slide the chest piece slowly around the left chest area near the typical apex location.

Move in small steps, pause, listen, then adjust. If you still can’t hear it well, you can use the finger method at the wrist as a backup.

Experience Notes: What It’s Like the First Few Times You Do This (And Why That’s Normal)

Let’s talk about the part nobody mentions: the first time you try to take your own pulse with a stethoscope,

it can feel weirdly hardlike your heart is playing hide-and-seek in a crowded room. That’s not because you’re “bad at it.”

It’s because listening is a skill, and your brain needs a few reps to learn what to focus on.

Most beginners start off hearing everything except the heartbeat: fabric scratch, hair brushing tubing, the faint rumble of the air conditioner,

even your own breathing. Your stethoscope is basically a microphone with commitment issuesit will faithfully amplify whatever sound is easiest to pick up.

The trick is to eliminate the noisy stuff: bare skin, steady hands, quiet environment, and tubing that isn’t swinging around like a jump rope.

Once you reduce the “extras,” the heartbeat usually pops into clarity like a song you suddenly recognize on the radio.

Another common experience: your heart rate may seem higher the moment you start listening. That’s because concentrating can make you tense,

and tension can nudge your heart rate up. People also hold their breath without realizing it (ironically while trying to listen to heart sounds).

If you notice your count is higher than expected, pause, take a few slow breaths, and measure again after a minute.

You’re not “changing your heart rate with your mind” like a superherojust normal physiology responding to stress and attention.

You may also notice that the best spot to hear your heart can shift slightly depending on posture.

Sitting upright might make the sound a bit fainter, while lying downespecially turned slightly to your leftcan make it louder and clearer.

That posture difference can feel dramatic, like your heart suddenly moved houses. It didn’t; the acoustics changed.

The heart’s position relative to the chest wall varies with body position, and sound travels differently through tissue.

That’s why repeating measurements in the same posture helps you compare apples to apples (and not apples to “why is my heart louder today?”).

Some people get spooked by tiny irregularities: an occasional pause, a beat that feels stronger, or a moment where the rhythm seems off.

It’s easy to jump to worst-case scenarios after one funky-sounding minute. But occasional variations can happen for many reasonsbreathing patterns,

stress, stimulants, fatigue, and normal rhythm changes that come and go. What matters is the pattern over time and whether you have symptoms.

If you hear frequent irregularity, can’t get a consistent rhythm across multiple checks, or you feel unwell, that’s the moment to contact a professional.

The stethoscope is your measurement tool, not your diagnosis machine.

A surprisingly satisfying “level up” moment happens when you stop thinking of the heartbeat as a blur and start hearing a pattern:

lub-dub… lub-dub… lub-dub. Once that clicks, counting gets easier, and you’ll probably get faster at finding the apical spot.

Many people also like to keep a small log for a weekespecially if they’re starting a new fitness routine, changing sleep habits,

or just curious about their baseline. Seeing your own numbers trend over time turns this from a one-off trick into a useful health habit.

Finally, there’s the oddly comforting part: hearing your own heart can make your body feel more realin a good way.

It’s a reminder that your system is running 24/7, even when you’re just sitting there with a stethoscope and a timer, trying not to drop the math.

And if you do drop the math? Congratulations. You are officially human.

Conclusion

Taking your own pulse with a stethoscope is a simple, practical skill that can make you more aware of your healthwithout turning you into a self-diagnosing tornado.

Find the apical spot, listen for “lub-dub,” count carefully, calculate BPM, and repeat when needed. Over time, you’ll get faster, more accurate,

and a lot less intimidated by the sound of your own heartbeat.

If you want the biggest takeaway: consistency beats perfection. Measure the same way, in a calm moment, and track trends.

And if you notice major changes or symptoms, let a professional interpret what your heart is trying to say.