Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Out of Fuel” Means in Space (Spoiler: It’s Not About Speed)

- How Kepler Worked: The Art of Watching Stars Blink

- Kepler’s Fuel Crisis: A Slow, Predictable, and Still Emotional Finale

- What Kepler Discovered: A Galaxy That’s Packed With Planets

- Why the End of Fuel Didn’t End the Mission’s Impact

- Lessons From Kepler’s Fuel Gauge: What Spacecraft Aging Teaches Us

- of Experiences: What It Felt Like to Watch Kepler Run Low

If you’ve ever watched your car’s fuel gauge slide toward “E” and thought, “I can make itprobably”,

you already understand the mood aboard NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope in its final stretch. The difference is that

Kepler wasn’t trying to limp to a gas stationit was trying to keep finding worlds hundreds (or thousands) of light-years

away while running on the cosmic equivalent of fumes.

The headline “Kepler is almost out of fuel” wasn’t clickbait. It was a real, mission-defining limit: without propellant,

the spacecraft can’t reliably point at stars, communicate with Earth, or keep itself stable for high-precision science.

And for a telescope built to measure tiny, precise dips in starlight, “stable” isn’t a nice-to-haveit’s the whole job.

What “Out of Fuel” Means in Space (Spoiler: It’s Not About Speed)

Spacecraft fuel isn’t always about going faster. For Kepler, fuel (specifically hydrazine propellant) mattered because it helped

control the spacecraft’s orientationthink of it as steering, not driving. A space telescope must aim with absurd consistency.

If it wobbles, rotates, or drifts, the light curve data gets noisy, and a planet’s faint “blink” can disappear into the static.

Kepler used a combination of control systems over its life, including reaction wheels (spinning devices that rotate the spacecraft without

expelling fuel) and thrusters (small jets that use propellant). When fuel runs low, mission teams can sometimes “stretch” operations by limiting

maneuvers, reducing adjustments, and parking in safe configurations that sip propellant. But eventually, physics wins.

Why Pointing Is Everything for a Planet-Hunting Telescope

Kepler’s superpower was patience. It stared at stars and tracked tiny changes in brightness. When a planet passes in front of its star from our viewpoint,

the star’s light dipsoften by far less than 1%. That’s the transit method, and it’s like spotting a gnat crossing a stadium spotlight… from miles away.

So when the spacecraft’s ability to hold a steady gaze depends on fuel, “almost out” becomes a countdown clock for discovery.

Not because Kepler couldn’t keep lookingbut because it couldn’t keep looking well enough.

How Kepler Worked: The Art of Watching Stars Blink

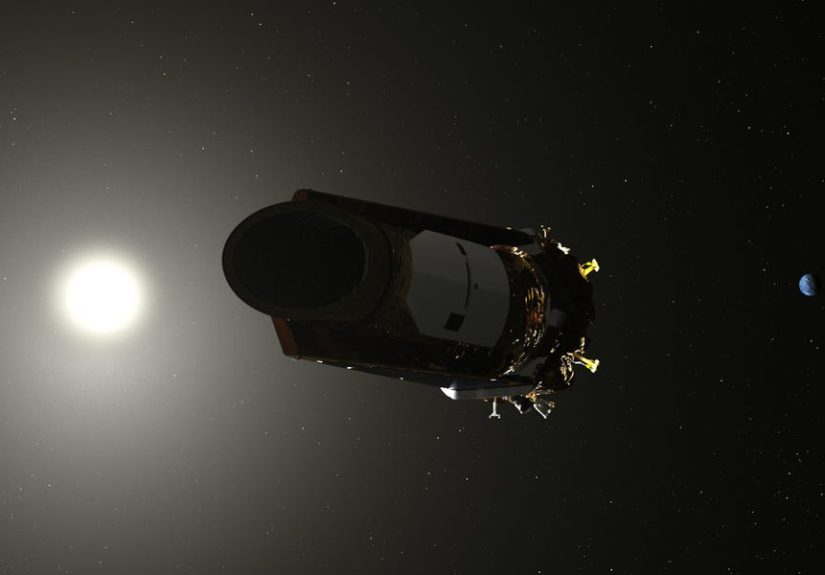

Launched in 2009, Kepler was designed to measure star brightness with extreme precision and uncover Earth-size planetsespecially those in or near

the “habitable zone,” where liquid water could exist under the right conditions. It monitored a large patch of sky and collected a flood of photometric

data that scientists could mine for years.

In its primary mission, Kepler repeatedly observed about 150,000 stars in a fixed field of view, looking for periodic dips that repeat like a metronome.

One dip might be noise. Two might be luck. But repeated dips spaced evenly in time? That’s the kind of pattern that makes astronomers sit up straight

and whisper, “Possible planet.”

From Raw Starlight to “Confirmed Exoplanet”

Kepler didn’t “photograph” planets directly most of the time. It measured starlight and produced light curves. Researchers then used statistical tests,

follow-up observations, and complementary methods (like radial velocity measurements from ground-based telescopes) to confirm which signals were truly planets.

It was detective work at galactic scale.

That’s why Kepler’s legacy isn’t just the planets it confirmedit’s also the catalog of candidates and the data archive that keeps producing new discoveries

long after the spacecraft stopped collecting fresh photons.

Kepler’s Fuel Crisis: A Slow, Predictable, and Still Emotional Finale

Kepler’s end wasn’t a sudden disaster. It was more like a candle burning down to the last waxvisible, measurable, and strangely dramatic because everyone

could see the finish line approaching.

By 2018, NASA teams were managing Kepler’s remaining propellant carefully. In mid-2018, the spacecraft paused science observations after onboard sensors indicated

low fuel, and controllers used low-fuel strategies (including placing it in a stable, minimal-fuel state) while planning data downlinks and limited operations.

The goal wasn’t to keep Kepler going forever; it was to get every last clean batch of data home.

The Reaction Wheel Twist That Made Fuel Even More Precious

Kepler’s story includes one of the most creative “mission save” moves in modern astronomy. The original Kepler mission depended on reaction wheels for precise pointing.

When multiple reaction wheels failed, the spacecraft could no longer maintain the same ultra-stable orientation in its original configuration.

Engineers and scientists responded by reinventing how Kepler could operate, using clever balancing techniques that incorporated solar pressure and the remaining hardware.

That extended Kepler’s life in a new observing mode known as the K2 missiondifferent targets, different cadence, same hunger for planets.

The catch: operating in this new reality made attitude control and operational margins tighter. In other words, the fuel became even more valuable.

The Official Goodbye: Retirement After a Historic Run

On October 30, 2018, NASA announced that Kepler had run out of fuel required for further science operations and would be retired in a safe orbit.

The spacecraft wasn’t “dead” in the dramatic sci-fi sense; it simply couldn’t do its job anymore. NASA’s messaging was clear: the mission ended,

but the science would keep coming.

What Kepler Discovered: A Galaxy That’s Packed With Planets

Kepler didn’t just find planetsit changed the baseline assumptions of astronomy. Before Kepler, exoplanets were exciting but still felt like special cases:

“Look, we found one!” After Kepler, the question became: “How many planets are in every planetary system?”

By the time it retired, Kepler had helped confirm more than 2,600 exoplanets and revealed thousands more candidates. NASA also published mission “by the numbers”

snapshots highlighting the telescope’s sweeping observational recordhundreds of thousands of stars observed over nearly a decade, and a discovery tally that transformed

the field.

Signature Finds That Made People Believe (and Then Google “Exoplanet” at 2 a.m.)

-

Earth-size planets in potentially temperate zones: Kepler delivered landmark discoveries that proved small planets exist around other stars

and that some orbit in regions where conditions could allow liquid waterone of the key ingredients for life as we know it. -

Systems that don’t look like ours: Kepler found compact multi-planet systems, planets orbiting close to their stars,

and worlds in configurations that made our solar system look like just one option among many. -

Statistics that changed the conversation: Kepler’s biggest “planet” might actually be a number:

the realization that planets are commonpossibly the default outcome of star formation.

In 2016, NASA announced one of the largest single collections of verified planets in one releasean example of how Kepler’s pipeline and validation methods matured over time,

turning massive candidate lists into confirmed worlds at scale. That shift mattered because it moved exoplanets from rare curiosities to a population you can analyze.

Why the End of Fuel Didn’t End the Mission’s Impact

Even after Kepler stopped observing, its data remained (and remains) scientifically alive. Researchers continue to:

- reprocess archival light curves with improved algorithms,

- validate overlooked candidates,

- refine estimates of how common Earth-size planets might be,

- and select targets for follow-up by newer observatories.

Kepler also handed off the “planet-hunting torch” to newer missions. The most direct successor in spirit is TESS (the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite),

which focuses on closer, brighter starsideal for follow-up studies with powerful telescopes. Meanwhile, missions and observatories like JWST can study atmospheres

of some exoplanets discovered by transit surveys, pushing from “planet found” toward “planet characterized.”

The Quiet Genius of “Retire in a Safe Orbit”

There’s something poetic and practical about retiring a spacecraft responsibly. NASA’s retirement plan placed Kepler in a safe orbit away from Earth.

That choice reduces the risk of future interference and reflects a growing norm in space operations: plan the end from the beginning, even if the middle becomes legendary.

Lessons From Kepler’s Fuel Gauge: What Spacecraft Aging Teaches Us

Kepler’s final chapter is a masterclass in how space missions actually end. Not with explosions, not with dramatic musicjust with fewer options.

A spacecraft is a balance of systems: power, thermal control, communications, pointing, onboard computing, and (yes) propellant. When one margin shrinks,

everything else has to become more conservative.

The takeaway isn’t “space is hard” (though it is). The takeaway is: space missions are negotiated miracles.

Kepler delivered nearly a decade of discovery, including a reinvention after hardware failures, and then extracted as much science as possible as fuel ran low.

That’s not luck. That’s engineering plus operations discipline plus scientific flexibility.

of Experiences: What It Felt Like to Watch Kepler Run Low

Kepler’s “almost out of fuel” moment wasn’t just a technical updateit landed like a cultural event for anyone who followed space science. There was a distinct,

shared feeling in classrooms, astronomy clubs, research groups, and even casual science corners of the internet: a mix of “we knew this was coming” and

“wait… it’s really happening.”

For students and educators, Kepler’s fuel countdown became an unexpectedly powerful teaching tool. It’s one thing to explain that spacecraft require propellant for attitude

control; it’s another thing entirely to tell a class, “This mission that helped change how we understand the galaxy is now making decisions based on its last drops of fuel.”

Suddenly, physics feels less like a chapter and more like a plot twist. Lessons about reaction wheels, solar pressure, safe mode, and communications windows stop being abstract.

They become the reason a world-discovering telescope might need to take a “nap.”

For researchers, the experience was both stressful and oddly energizing. When a mission nears its operational end, there’s a sprint mentality:

get the data down, prioritize observations, and lock in the final campaigns. You can almost imagine the mission planning meetings with a giant invisible

stopwatch on the wall. Decisions that might have taken months suddenly feel urgent. Every maneuver becomes a question:

“Is this worth the fuel?” There’s a special intensity in knowing the instrument is still capable of discovery, but the spacecraft is approaching a hard limit.

For citizen scientists and space fans, the fuel news created a “Kepler appreciation season.” People revisited favorite discoveriesplanets that orbit two suns,

rocky candidates in temperate zones, tightly packed systems that look nothing like ours. Social feeds and science sites filled with retrospectives, diagrams,

and heartfelt posts that sounded surprisingly personal for a telescope: “Thank you, Kepler.” That sounds silly until you realize how many people felt

genuinely connected to a mission that expanded the idea of what a “normal” solar system could be.

And then there was the quiet after the announcement. Not disappointment exactlymore like the feeling after a great concert ends and the lights come up.

You’re not sad because it was bad; you’re sad because it was good, and it’s over. But Kepler left a gift that doesn’t expire: the data.

The experience of Kepler running low wasn’t only about an endingit was also about the reassuring truth that science doesn’t stop when the spacecraft does.

The telescope may have run out of fuel, but the universe it revealed is still waiting in the archive, blinking patiently, ready for the next set of eyes

(and algorithms) to notice.