Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Who Was Margaret Horton, and What Did a WWII Flight Mechanic Actually Do?

- Why Would Anyone Sit on the Tail of a Spitfire?

- The Day the Routine Job Turned Into an Extremely Unroutine Flight

- How Do You Survive Hanging Onto a Fighter Plane?

- How the Pilot Realized Something Was Off

- Aftermath: Cigarettes, Berets, and the Weirdness of “Back to Work”

- What Actually Caused the Accident?

- Why This Story Still Matters: Human Factors Don’t Expire

- The Spitfire, the Airfield, and the Wider Wartime Context

- Quick FAQ: The Questions Everyone Asks First

- Experiences Related to “Rode Atop a Plane by Accident” (Modern Lessons From Tailwheel Reality)

- Conclusion

Some World War II stories sound like they were written by a screenwriter who’d been told, “Make it believable,” and replied,

“Define believable.” The tale of Leading Aircraftwoman Margaret Hortona Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) flight mechanic

accidentally taking flight while clinging to the tail of a Supermarine Spitfire is one of those stories.

It’s funny in hindsight, terrifying in the moment, and surprisingly useful as a real-world case study in human factors,

communication breakdowns, and why “standard procedure” can become “standard chaos” if one detail goes missing.

This article breaks down what happened, why anyone was sitting on a Spitfire in the first place, what the incident reveals about WWII-era

flight-line life, and what modern aviation still learns from moments when a routine task turns into an unplanned adventure.

Who Was Margaret Horton, and What Did a WWII Flight Mechanic Actually Do?

Margaret Horton served as a WAAF flight mechanic during WWII, working around RAF operations where aircraft were constantly being serviced,

checked, moved, and launchedoften under time pressure and imperfect conditions. The WAAF existed to fill critical roles so more men could be

assigned to combat duties, and women worked across a wide range of trades, including aircraft maintenance and repair.

Even so, WAAF personnel were not intended to be aircrew. Horton wasn’t supposed to be “going flying”certainly not as an unbelted

passenger on the outside of a fighter.

If you picture a WWII flight mechanic’s day as glamorouswind in the hair, hero music, slow-motion high fivesswap that image for cold hands,

heavy boots, oily tools, rushed checklists, and weather that never seems to cooperate. The work mattered. A mechanic’s inspection, adjustment,

or fix could determine whether an aircraft returned safely.

Why Would Anyone Sit on the Tail of a Spitfire?

The short answer: physics and wind are rude. The longer answer: the Spitfire was a high-performance aircraft designed with priorities like speed,

climb rate, and combat effectivenessnot “easy and relaxed ground handling on bumpy grass fields.”

In rough weather, especially with strong winds and uneven surfaces, light aircraft can be pushed around while taxiing. A Spitfire’s ground behavior

could become especially twitchy because of design traits like a relatively narrow landing-gear track and classic tailwheel dynamics.

One practical solution used on some stations was a “rough weather” procedure: a ground crew member would add ballast by sitting on the tailplane or

rear fuselage while the aircraft taxied, helping keep it stable until it reached the runway position where the person would hop off.

It wasn’t elegant. It wasn’t comfortable. And it definitely wasn’t meant to continue past the point where the pilot applied takeoff power.

But it was a workaround that made sense on a windy day when you needed that fighter to taxi without pitching, tipping, or misbehaving like a shopping cart

with one bad wheel.

The Key Detail: The Tail-Sitter Must Be Seen (or at Least Understood)

A procedure like this only works if everyone shares the same mental model: the pilot knows a tail-sitter is present, the tail-sitter knows the

pilot knows, and there’s a clear signal for “I’m getting off now.” In some versions of the story, the planned signal involved grabbing and moving

the elevator to get the pilot’s attentionessentially a mechanical “hey!” from the back end of the aircraft.

And that brings us to the entire problem: on the day in question, the pilot did not have the message that “rough weather procedure” was in effect,

and he did not realize Margaret Horton was still on the aircraft when he transitioned from taxi to takeoff.

The Day the Routine Job Turned Into an Extremely Unroutine Flight

The incident is usually placed in February 1945 at RAF Hibaldstow in Lincolnshire (a satellite field associated with nearby operations).

Accounts commonly name the pilot as Flight Lieutenant Neill (or Neil) Cox and the aircraft as a Spitfire thatdepending on the sourceis identified by

different codes/serial references connected to aircraft on that station.

Why the disagreement? Wartime documentation, retellings, and later summaries don’t always line up neatly. Some timelines give a specific date,

others round it to “mid-February,” and a few listings attach it to different aircraft identifiers. The consistent spine of the story remains the same:

Horton climbs onto the tail to act as ballast, the pilot is unaware (or loses track), the aircraft accelerates for takeoff, and Horton ends up airborne.

The Moment She Knew Something Was Wrong

Horton’s own recollection (shared after the war) describes the first warning as the aircraft suddenly taxiing much fasterbecause the pilot had moved

from “rolling out” to “committed to launch.” Horton tried to get the pilot’s attention by grabbing at the tail controls, but quickly realized she couldn’t

safely jump off and couldn’t make herself known in time.

If you’ve ever missed the last step off a treadmill, you already understand the vibeexcept this treadmill has a Merlin engine and the consequences are

“become a cautionary tale for the next 80 years.”

How Do You Survive Hanging Onto a Fighter Plane?

The most remarkable part of the incident isn’t that it happened (humans are impressively consistent at creating preventable surprises). It’s that Horton survived.

She reacted fast: instead of staying perched in a way that would let wind peel her off, she repositioned herself across the rear fuselage/tail cone area,

using the vertical fin as a bracelegs on one side, torso on the otherclinging with a limited grip.

Reports describe her gripping a cutaway or handhold area with just a few fingers. That small detail matters, because it explains why she couldn’t simply “wave.”

She was busy doing the world’s least enjoyable pull-up while a high-powered aircraft gained speed and climbed.

What the Flight Looked Like From the Tower (and Why the Pilot Didn’t Know)

From the cockpit of a WWII fighter, visibility is not “full panoramic awareness of everything happening behind the tail.” If the pilot hadn’t been briefed that a

tail-sitter was present, he might interpret odd handling as a mechanical issue rather than “surprise mechanic attached.”

In retellings, someone on the ground realized what was happening and alerted control. The pilot was instructed to landquicklywithout necessarily being told why

(which is both understandable in an emergency and also deeply on-brand for the military: “Do this now; explanation available after you’ve stopped doing the dangerous thing.”).

How the Pilot Realized Something Was Off

Horton’s presence wasn’t just a passenger problem; it affected the aircraft. Any extra weight at the tail changes balance and handling. On top of that,

a person gripping or interfering near the tail surfaces could make the elevator feel “wrong,” or at least different enough that the pilot would report control anomalies.

Some accounts describe the pilot calling in that the tail assembly wasn’t responding properly.

The pilot brought the aircraft around and landed safely. Horton remained onboard through touchdownso gently, in some recollections, that she didn’t immediately

register the moment the wheels met the ground again.

Aftermath: Cigarettes, Berets, and the Weirdness of “Back to Work”

One of the most human details in this story is the reaction afterward. In a famous retelling, Horton joked that after a change of underwear and a cigarette,

she’d be fine to return to duty. Humor is a common coping tool in high-stress environments, and wartime flight lines were nothing if not high-stress.

There’s also the detail that she was reportedly fined for losing her beret during the ordeal.

If that’s true, it’s a perfect micro-summary of military life: “Yes, you survived an impossible event. However… about that uniform item.”

What Actually Caused the Accident?

This wasn’t a “mystery physics event.” It was a chain of small, understandable failures that lined up like dominoes:

- Procedure without universal awareness: The “rough weather” method depended on a briefing that didn’t reach the pilot.

- Limited cockpit visibility: Even if Horton was on the aircraft, the pilot couldn’t easily confirm it visually.

- Ambiguous signaling: A hand gesture or assumed cue was misread, or the normal “I’m hopping off” signal didn’t happen in time.

- Time pressure and routine thinking: When tasks become habitual, people skip verification stepsespecially in wartime tempo.

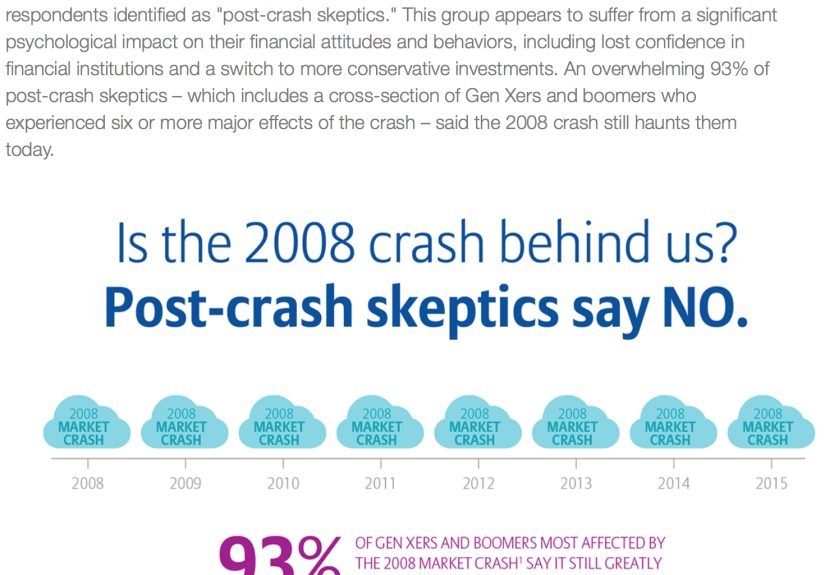

In modern safety language, you’d call this a breakdown in shared situational awareness. In plain English: everybody thought everybody else knewuntil the Spitfire

started acting like it was carrying a secret.

Why This Story Still Matters: Human Factors Don’t Expire

You don’t need to maintain a WWII fighter to learn from Horton’s experience. The incident highlights timeless lessons:

1) “Standard Procedure” Needs a Standard Confirmation

Procedures that rely on memory and assumption are fragile. The more dangerous the step, the more it should require a clear, unmistakable confirmation.

Modern aviation leans heavily on checklists and callouts for this reasonbecause humans are excellent at forgetting the one detail that matters most.

2) Communication Must Be Redundant When the Stakes Are High

One method of communication (a signal, a note, a shouted instruction) can fail. Redundancymultiple independent ways to confirm the same critical pointprevents

“single-point failure” moments like “pilot didn’t get the rough weather order.”

3) Workarounds Are Real Solutions… Until They Aren’t

The tail-sitter method was a practical workaround. But workarounds always carry hidden risk, especially when they place a person in a position where the margin

for error is thin. Horton’s story is a reminder to treat workarounds as temporary, managed hazardsnot casual routine.

The Spitfire, the Airfield, and the Wider Wartime Context

RAF Hibaldstow served as a station associated with training and operations in the later war years, and accounts of Horton’s incident often appear alongside

broader summaries of the airfield’s history. The aircraft involved is commonly associated with a Spitfire that had a notable service record and later became part

of the long afterlife many warbirds enjoyrestored, flown commemoratively, and remembered through stories like this one.

That afterlife is part of what keeps Horton’s story circulating. The public often encounters it through aviation history features, museum contexts, and modern

write-ups that use it as an example of “truth stranger than fiction.” And it endures because it captures something real:

the war was fought not only by pilots in the sky, but by mechanics, fitters, and ground crews whose jobs were dangerous in ways history books don’t always highlight.

Quick FAQ: The Questions Everyone Asks First

Did this really happen?

Yes. The incident is documented in multiple historical and institutional retellings, including versions based on Horton’s own postwar account and later aviation

history compilations.

Was it “legal” or authorized?

The tail-sitting portion was treated as a rough-weather ground procedure on some stations. The takeoff with a person still attached was not intended and

was immediately treated as an emergency situation.

How long was she in the air?

Most accounts describe a short circuit/pattern and immediate landing rather than an extended flight. Enough time to be terrifying. Not enough time to start a

frequent-flyer program.

Experiences Related to “Rode Atop a Plane by Accident” (Modern Lessons From Tailwheel Reality)

Margaret Horton’s story lives in a specific WWII setting, but the sensations and risks it hints at are still familiar to people who work around

tailwheel aircraft and warbirds todayespecially on windy days, uneven surfaces, and during high-tempo operations. When modern pilots talk about transitioning

to tailwheel aircraft, one theme comes up again and again: the airplane will happily punish a lapse in directional control. That’s not drama; it’s geometry.

In a tailwheel design, the center of gravity sits behind the main wheels, which can amplify a swerve into a rapid pivot if it isn’t corrected immediately.

Aviation handbooks describe how ground loops start with a swerve that continues too long, and how small errors can build fast into a loss of control.

Those “seat-of-the-pants” experiencesfeet working the rudder, eyes locked down the runway line, corrections made early and lightlyare part of what makes

tailwheel flying a skill and a discipline. Organizations that teach tailwheel technique often emphasize training that builds reflexes and peripheral awareness,

because by the time you feel the problem, you may already be behind it. That’s why instructors drill students to keep the aircraft tracking straight through

the rollout and to avoid overcorrections that start oscillations. If that sounds familiar, it should: Horton’s story begins with a ground-handling problem

(wind and stability while taxiing) and becomes a crisis because one small linkcommunicationfailed.

Ground crews around warbirds learn their own set of “real experiences” that don’t show up in glossy posters. First: prop wash is not a gentle breeze.

Second: hand signals must be standardized, unambiguous, and confirmedespecially when hearing protection and engine noise remove the option of normal conversation.

Third: procedures that put a person near control surfaces or in unusual positions must include a fail-safe. In Horton’s case, the normal “I’m hopping off” cue

didn’t happen in time. Today, many operations mitigate that kind of risk by using chocks, tow bars, wing walkers, radios, or specific hold-short checkpoints where

the aircraft must stop until ground crew are clear and a final “all clear” is given.

Pilots also describe a very specific experience that echoes the pilot side of Horton’s incident: the feeling when an airplane is “not responding right,” even if

you can’t immediately identify why. Modern training encourages pilots to treat abnormal control feel as a reason to stop, slow down, or abort, because hidden

problems on the ground can be surprisingly variedbrake dragging, tailwheel misalignment, gusty crosswinds, a control lock left in place, or a mechanical issue.

In Horton’s story, the pilot reportedly sensed something off in the tail response. That instinctrecognize abnormality early, choose the conservative option, and

return to the groundremains one of aviation’s most practical survival skills.

Finally, there’s the human experience: how people process a near-miss. Warbird communities, flight lines, and training hangars still run on the same emotional fuel:

adrenaline, focus, and (afterward) humor. The “change of underwear and a cigarette” line endures because it captures what many aviators and maintainers recognize:

you can be terrified and competent at the same time, and laughter afterward is often the brain’s way of filing the event under “we survived; let’s learn from it.”

Horton’s accidental ride isn’t just a quirky anecdote. It’s a vivid reminder that aviation safety is built from thousands of small disciplinesclear signals,

verified procedures, and the humility to assume that if something can be misunderstood, one day it will be.

Conclusion

“WWII Flight Mechanic Margaret Horton Rode Atop a Plane by Accident” sounds like a headline designed to grab clicksand it doesbut it also describes a real

event with real lessons. Horton’s survival came down to quick thinking, physical grit, and a pilot who chose the safe option when the aircraft didn’t feel right.

The accident itself came from something more ordinary: a missing briefing, a misunderstood signal, and a routine workaround treated as normal.

The reason the story lasts isn’t just because it’s wild (though it absolutely is). It lasts because it’s human. And because aviationthen and nowstill depends on

humans getting the small things right before the big things start moving.