Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why “health care at home” is booming

- The promise: why home can be the best “facility”

- The cracks: who gets left behindand why

- 1) Coverage rules that don’t match real life

- 2) The HCBS waitlist problem (the quiet crisis)

- 3) The workforce bottleneck: you can’t deliver care without humans

- 4) Family caregivers: the shadow workforce holding everything up

- 5) Housing instability: what if “home” isn’t safeor doesn’t exist?

- 6) The digital divide: telehealth helps… unless you can’t connect

- What falling through the cracks looks like (composite examples)

- How we close the cracks (without pretending it’s easy)

- 1) Treat HCBS as essential infrastructure, not optional extras

- 2) Pay the workforce like the workforce is the plan

- 3) Build caregiving support into health care, not as an afterthought

- 4) Integrate health care with housing and social supports

- 5) Make tech a bridge, not a gate

- 6) Measure equity, not just efficiency

- What families can do right now (practical steps)

- Conclusion: home can be the best site of careif we stop pretending everyone starts from the same place

- Experiences from the home front

The American health care system has a new favorite address: yours. Not your insurance company’s mailing address, not your primary care office’s fax machine

(yes, it’s still wheezing along), but your actual homewhere the dog judges your life choices and the “waiting room” has snacks you didn’t overpay for.

For a lot of people, care at home is safer, calmer, and surprisingly high-tech. Think: nurses visiting with tablets, remote monitoring that pings your care team

if your blood pressure goes rogue, and even “hospital-at-home” models that bring acute-level care to the living room.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: “home” is a great place for health care… if you have one, if it’s safe, if you can get the right services, and if the rules

of coverage don’t treat your needs like a technicality. Millions of Americans can’t access home-based careor can’t keep it goingbecause they land in the cracks:

waitlists, workforce shortages, confusing eligibility criteria, lack of broadband, unstable housing, or a family caregiver who is already running on fumes and cold coffee.

This article walks through why health care is moving home, what’s working, where it’s breaking, and what it would take to stop people from falling through the

floorboards. We’ll keep it real, we’ll keep it practical, and yes, we’ll occasionally laughbecause if we can’t laugh at the idea of coordinating home health paperwork,

we might cry into the prior authorization forms.

Why “health care at home” is booming

Home-based care isn’t a trendy lifestyle choice like sourdough starters or standing desks. It’s a response to big forces colliding: an aging population, more people living

longer with chronic conditions, hospital capacity constraints, and the simple fact that many patients recover better when they’re not sleeping under fluorescent lights while

a hallway IV pole squeaks at 2 a.m.

Done well, health care at home can reduce infections, prevent unnecessary hospital stays, and improve patient experience. It can also be a smarter use of resources:

you can reserve hospitals for patients who truly need them and support recovery in a place people actually want to be. And for many families, it’s the only realistic option

because taking off work, arranging transportation, and juggling multiple specialists is a logistical Olympic sport.

What counts as home-based care?

“Home-based care” isn’t one thing. It’s a whole menu:

- Medicare home health services (typically intermittent skilled nursing, therapy, and aide services, under specific criteria).

- Home- and community-based services (HCBS) under Medicaid (often personal care, supports for disability, and long-term services).

- Home-based primary care for medically complex or home-limited patients.

- Remote patient monitoring (blood pressure cuffs, glucose sensors, weight scalesbasically, your bathroom becomes a mini-clinic).

- Telehealth (video visits, phone visits, and asynchronous check-ins).

- Hospital-at-home / Acute care at home (select patients receive hospital-level services at home with close monitoring).

- Post-acute care support after hospitalization (medication management, wound care, rehab exercises, fall prevention).

The headline is simple: more care can happen outside hospital walls. The fine print is where the cracks start.

The promise: why home can be the best “facility”

Home is where routines live. It’s also where health problems show their true colors. A clinic visit might tell you a patient’s blood pressure is high. A home visit might

tell you the patient can’t reach their medications because the stairs are unsafe, the fridge is empty, and the only working light bulb is in the microwave.

Home-based care can:

- Catch problems early (weight gain that signals heart failure flare-ups, missed medications, infection signs).

- Reduce avoidable ER visits (especially for people with chronic disease who need frequent tuning, not emergency sirens).

- Support caregivers with training and a care plan (instead of tossing them into the deep end with a hospital discharge packet).

- Improve functional independence (therapy in the actual environment where someone needs to walk, bathe, and cook).

- Align care with patient goals (including serious-illness care and comfort-focused approaches when appropriate).

And let’s be honest: a lot of people are more candid at home. In a clinic, someone might say, “Sure, I’m taking my meds.” At home, you might find the bottles unopened,

because the copay was too high and the patient had to choose between pills and groceries.

The cracks: who gets left behindand why

Here’s the part we don’t say loudly enough: home-based care is often built for people who already have stability. If your life is steadyhousing, phone, transportation,

insurance, supportive familyhome care can be amazing. If your life is already a Jenga tower, one missing service can topple everything.

1) Coverage rules that don’t match real life

Medicare home health, for example, can be a lifelinebut it is not designed to provide unlimited long-term daily help. Many people assume “home health” means “someone will

come every day and do whatever I need.” In reality, Medicare home health generally requires meeting eligibility criteria and usually covers intermittent skilled services and

related supports, not round-the-clock personal care.

Medicaid HCBS can provide longer-term supports, but access varies dramatically by state and program type. Many states use waiver or program structures that limit enrollment.

The result? Waitlists and “interest lists” that can stretch for months or years, depending on where you live and what category you qualify under.

Quick reality check: If your ZIP code determines whether you can get help bathing safely, that’s not “personal responsibility.” That’s a policy decision wearing a trench coat.

2) The HCBS waitlist problem (the quiet crisis)

“Home is best” is a popular slogan. But if you need Medicaid-funded home care and your name sits on a list that barely moves, home becomes a place where unmet needs

accumulatefalls, caregiver burnout, missed appointments, and preventable hospitalizations.

Waitlists don’t just affect older adults. They affect people with disabilities, people with complex behavioral health needs, and families trying to keep loved ones at home

instead of in institutions. When supports don’t show up, the “default caregiver” is often a family memberfrequently a womanwho reduces work hours, drains savings, and

quietly absorbs the health system’s gaps.

3) The workforce bottleneck: you can’t deliver care without humans

Home health aides, personal care aides, and direct support professionals are the backbone of home-based care. Demand is soaring. But recruitment and retention are brutal:

the work is physically hard, emotionally demanding, and often paid like it’s “extra credit” instead of essential infrastructure.

In many communities, you can “qualify” for services on paper but still can’t get them in practice because agencies can’t staff the case. That gap is even sharper in rural

areas, where travel time is longer and agencies have fewer workers to spread around.

4) Family caregivers: the shadow workforce holding everything up

If home-based care were a building, family caregivers would be the load-bearing walls. They manage medications, monitor symptoms, provide transportation, help with bathing,

and coordinate appointmentsoften while working a paid job and raising kids. It’s not rare; it’s common.

The problem is that we treat caregivers like an unlimited resource. We assume they can take time off, learn complex clinical tasks overnight, and never get sick themselves.

Then we act surprised when they burn out.

Caregiving strain is not just emotional. It’s financial: lost wages, reduced retirement savings, out-of-pocket costs for supplies, and the constant drip of “small” expenses

that add up fast. When caregiving collapses, people end up in crisis careER visits, hospital admissions, or nursing facilitiesbecause there’s no other option.

5) Housing instability: what if “home” isn’t safeor doesn’t exist?

Home-based care assumes a stable, safe place to live. But hundreds of thousands of people experience homelessness on a given night in the U.S., and many more cycle through

unstable housing. For them, “recover at home” can be an impossible instructionlike being told to “just print the form” when you don’t have a printer, a computer, or a

place to plug in a charger.

This is where people fall through the cracks in the most literal way. Someone is discharged from a hospital with wound care needs, mobility limitations, or a new diagnosis

that requires follow-up. Without housing, medications get lost, infections worsen, and the person boomerangs back to the hospital. It’s expensive, it’s exhausting, and it’s

avoidable.

One promising bridge is medical respiteshort-term recuperative care for people experiencing homelessness who are too sick to be on the street but not sick

enough to require hospitalization. Medical respite programs can stabilize health, connect people to primary care, and improve the odds of housing placementbasically, they

give patients a fighting chance to heal somewhere that isn’t a sidewalk.

6) The digital divide: telehealth helps… unless you can’t connect

Telehealth and remote monitoring can be powerful, especially for mobility-limited patients. But they depend on broadband, devices, data plans, and digital literacy. If

you’re an older adult without reliable internet, or you rely on a phone plan that runs out of data mid-visit, “just hop on video” becomes a barrier dressed up as convenience.

Hybrid modelsphone options, in-person backup, community-based digital helpmatter if we don’t want innovation to widen disparities.

What falling through the cracks looks like (composite examples)

The “discharge-to-nowhere” loop

A man in his late 50s is treated for a serious infection. He’s medically stable for discharge but needs daily wound care for several weeks. He’s staying in a friend’s

garage, and the friend is moving. Home health can’t take him because there’s no stable address and no refrigeration for supplies. He’s sent out with instructions and a

follow-up appointment two weeks away. Three days later, he’s backfever, worsening wound, no clean dressings.

The waitlist squeeze

A mother caring for her adult son with significant disabilities applies for Medicaid HCBS supports. She’s told he’s eligible, but there’s an “interest list.”

Meanwhile, she’s lifting him, bathing him, and doing complex care tasks with no paid help. She develops a back injury. If she can’t provide care, he may be institutionalized

not because it’s best, but because it’s available.

The rural staffing gap

An older couple in a rural county qualifies for home health after a hospitalization. The agency accepts the referral but can’t staff it consistently because the nearest

nurse is an hour away and already covering multiple counties. Visits are delayed, medications aren’t reconciled, and a preventable complication becomes an emergency.

These aren’t edge cases. They’re system patterns: eligibility without access, discharge without support, innovation without infrastructure.

How we close the cracks (without pretending it’s easy)

The solution isn’t “more slogans about home.” It’s building a home-based care system that works for people with the least stabilitynot just those who already have a

strong support network.

1) Treat HCBS as essential infrastructure, not optional extras

- Reduce waitlists through expanded capacity and clearer pathways into services.

- Improve transparency so people can see what services exist, how long the wait is, and what alternatives are available.

- Align payments with reality so agencies can hire and keep workers.

2) Pay the workforce like the workforce is the plan

You can’t “innovate” your way around a staffing shortage. Better wages, benefits, training, and career ladders are not feel-good add-onsthey’re how care shows up on

Tuesday morning when someone needs help getting out of bed safely.

3) Build caregiving support into health care, not as an afterthought

- Offer caregiver training that is practical and ongoing, not a one-time pamphlet.

- Screen caregivers for burnout and connect them to respite and counseling supports.

- Make workplaces more caregiver-friendly (predictable scheduling, paid leave options).

4) Integrate health care with housing and social supports

If housing is health, then health care systems need real partnerships with housing providers, social service agencies, and community organizations. Medical respite,

supportive housing pathways, and “whole-person” approaches can reduce the revolving door of hospital readmissions and help people stabilize long enough to actually recover.

5) Make tech a bridge, not a gate

- Offer low-tech access (phone visits) when video isn’t feasible.

- Provide devices, training, and community digital support for older adults and low-income patients.

- Design remote monitoring programs that don’t assume perfect connectivity.

6) Measure equity, not just efficiency

If a hospital-at-home program works beautifully for patients with spare bedrooms and nearby familybut not for people in crowded housing or without broadbandthat should

show up in the quality metrics. Success should include who was reached, not just how many admissions were avoided.

What families can do right now (practical steps)

- Ask for a clear care plan at discharge: services needed, who orders them, and who follows up if they don’t start.

- Confirm eligibility and limits: What does Medicare home health cover? What doesn’t it cover? What’s the backup plan?

- For Medicaid HCBS: ask about state programs, waiver lists, and whether there are interim supports while you wait.

- Don’t go it alone: request a social worker or care manager referral if housing, food, or transportation is unstable.

- Support the caregiver: get training on medications and mobility; ask about respite resources early, not at the breaking point.

- Tech check: if telehealth is part of the plan, confirm broadband, device access, and a phone-based alternative.

Conclusion: home can be the best site of careif we stop pretending everyone starts from the same place

There really is no place like home when it comes to health carewhen home is safe, stable, connected, and supported by a workforce that can actually show up.

But a home-first strategy that ignores waitlists, workforce shortages, caregiver strain, housing instability, and the digital divide isn’t home-based care.

It’s hope-based care.

The goal isn’t to pull care back into institutions. The goal is to build a home-based system that’s strong enough to hold the people who are most likely to be dropped.

If we want “care at home” to be more than a nice idea, we have to design it for the cracksand then seal them.

Experiences from the home front

The stories below are composite experiencesblended from common scenarios described by patients, caregivers, clinicians, and community programs.

Names and details are generalized, but the challenges are very real.

1) The living room ICU (minus the ICU’s staffing)

A nurse describes arriving at a small apartment for a post-hospital visit and realizing the patient’s “recovery setup” is a recliner, a wobbly side table, and a pill

organizer that looks like it lost a fight with a toddler. The patient jokes, “Welcome to my deluxe suite.” The joke landsuntil the nurse learns the patient has been

rationing medications to make them last. The patient isn’t reckless; he’s doing math. Rent, food, electricity, meds. Something has to give.

The nurse spends half the visit on clinical care and the other half on detective work: calling the pharmacy, checking coverage, and trying to find a community program that

can help with transportation to follow-up appointments. The patient’s health problem is treatable. The system problem is that recovery requires resources the patient doesn’t

have. Home-based care becomes less “medical” and more “logistics plus compassion.”

2) The caregiver who becomes the patient

A daughter caring for her father after a stroke learns to do transfers, monitor blood pressure, and track medications. She’s prouduntil she’s exhausted. She sleeps in

fragments, listens for falls, and still logs into work every morning. Her friends text, “Let me know if you need anything!” which is kind, but also vague enough to be

useless at 2 a.m. when your dad is confused and trying to stand up.

After weeks of this, she develops migraines and panic symptoms. She tells herself she’s “fine” because her dad is the one who’s sick. But home-based care quietly

turned her into a second patientone without a care plan. When a social worker finally asks, “Who’s taking care of you?” she cries in the kitchen, holding a stack of

insurance letters that might as well be written in ancient Latin.

Her experience is common: caregiving can be meaningful, but it can also be isolating and destabilizing. The difference between “manageable” and “meltdown” is often

supportrespite services, training, a reliable home aide, and someone who can navigate benefits. Without those, family love becomes a substitute for policy.

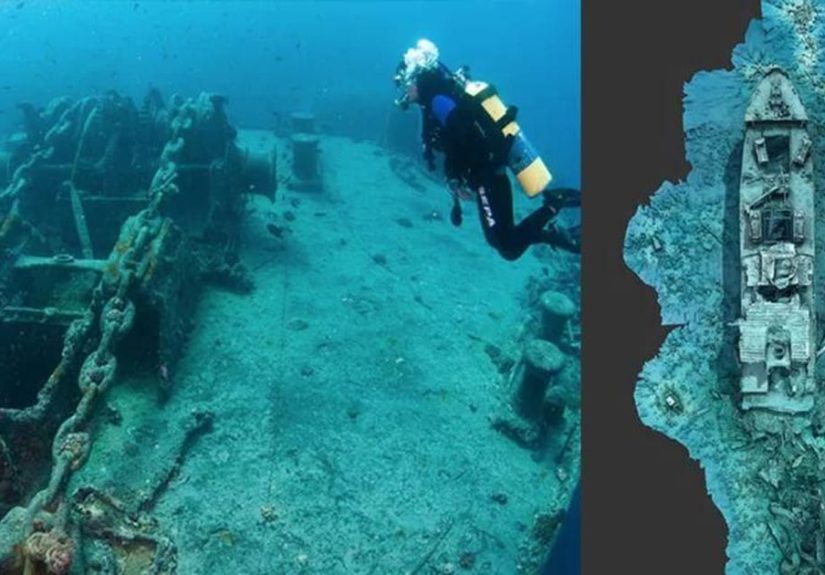

3) “Recover at home” when home is a car

Outreach workers describe meeting someone recently discharged from a hospital who’s trying to keep a surgical site clean while living in a vehicle. The person has a bag

of supplies and instructions to keep the area dry and watch for infection. They nod politely, because what else are you supposed to doargue with a discharge summary?

In reality, they’re improvising: using bottled water for basic hygiene, searching for a place to charge a phone, and trying to keep bandages from getting soaked in rain.

A follow-up appointment is scheduled across town, but transportation is unreliable. This is where the phrase “fall through the cracks” stops being a metaphor. The cracks are

structural: no housing, limited storage for medications, and a health care plan built on assumptions that simply don’t apply.

When medical respite or supportive housing is available, the difference can be immediate. A stable place to rest, consistent access to wound care, and a case manager who can

coordinate benefits can break the readmission cycle. The most striking part, workers say, is how quickly people improve when the basics are met. It’s a reminder that

“health care at home” isn’t only about where care happensit’s about whether someone has the foundation to heal at all.