Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- They scale before they’ve earned the right to scale

- Why this mistake happens (even to smart teams)

- The real root cause: confusing early demand with repeatable value

- How to tell if you’re scaling too early

- The fix: stop pouring gaspatch the bucket

- Three concrete examples (anonymized, but painfully real)

- A practical checklist to avoid the “biggest SaaS mistake”

- Conclusion: the biggest SaaS mistake is skipping the hard part

- 500+ words of “I’ve seen this movie before” experiences (and how it usually ends)

It’s not “bad code.” It’s not “a weak logo.” And it’s definitely not “we didn’t use enough synergy.”

The biggest mistake I’ve seen SaaS companies makeover and over, across different markets, price points, and founder personalitiesis this:

They scale before they’ve earned the right to scale

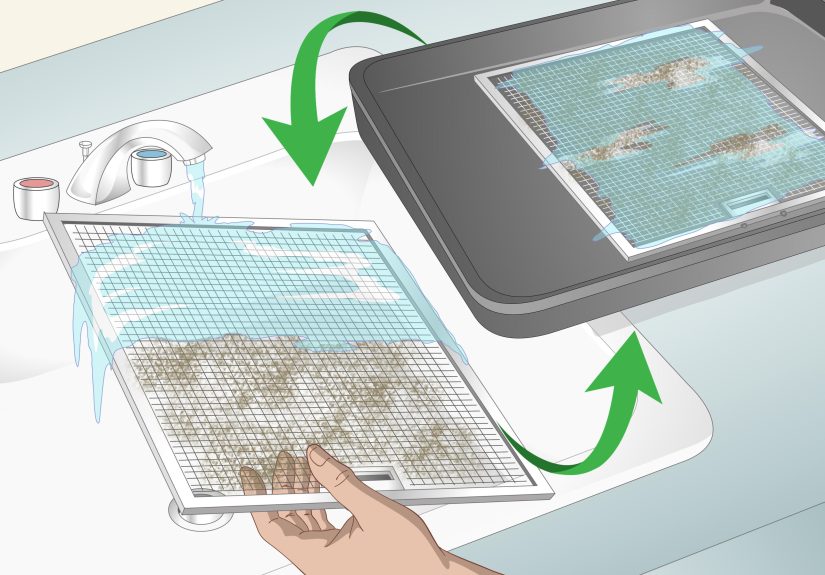

In plain English: they pour gasoline on a business that still has a leaky bucket.

They hire a bigger sales team before the product reliably sticks. They crank ad spend before onboarding reliably activates users. They expand into “enterprise” because it sounds like a fancy neighborhoodwithout realizing enterprise buyers bring a moving truck of requirements, security questionnaires, and procurement delays.

And when growth stalls, they assume the fix is… more scaling. (Because surely the third SDR team will be the charm.)

The leaky-bucket version of “growth”

Here’s what premature scaling tends to look like in the real world:

- Sales hired too early: you’re staffing for volume before you’ve proven repeatability.

- Marketing spend ramped too fast: you’re buying traffic to a product that hasn’t nailed time-to-value.

- Too many customer types: you say yes to everyone, then wonder why your roadmap looks like a junk drawer.

- Discounting as a strategy: you “win” deals by slicing price, then lose the ability to fund retention fixes.

- Feature sprawl: you build a buffet when customers actually needed one great entrée.

Why this mistake happens (even to smart teams)

Premature scaling isn’t usually laziness. It’s a cocktail of understandable forces:

1) Traction is loud. Retention is quiet.

New signups feel like progress. A spike in MQLs is thrilling. A big logo on the website makes everyone stand taller in Slack.

Retention, meanwhile, is a slow truth. It shows up in cohorts, renewals, usage patterns, and whether customers still love you after the honeymoon ends.

2) Vanity metrics are addictive

“We doubled signups!” sounds amazing. But if activation and retention aren’t improving, you might just be doubling the number of people who try your product… and then disappear forever.

3) Pressure (investors, competitors, your own ego)

Sometimes the pressure is external: “You should move faster.” Sometimes it’s internal: “If we aren’t growing fast, are we even a real SaaS company?” (Yes. You are. Breathe.)

Scaling can become performativelike buying a treadmill and assuming you’re now an athlete.

The real root cause: confusing early demand with repeatable value

Most “big SaaS mistakes” are really one mistake in different outfits:

They mistake early demand for product-market fitand product-market fit for go-to-market fit.

Product-market fit vs. go-to-market fit (the difference that saves companies)

- Product-market fit means a specific customer segment gets ongoing value and keeps using (and paying for) the product.

- Go-to-market fit means you can acquire those customers repeatedly and profitably with a sales/marketing motion that matches how they buy.

A SaaS company can have customers who love the product and still failbecause it can’t find them efficiently, onboard them consistently, and retain them predictably.

How to tell if you’re scaling too early

If you want a quick diagnostic, don’t start with “How’s pipeline?” Start with “Do customers stick?”

Watch these red flags

- Churn that won’t behave: customers leave before they reach the “aha” moment, or they churn right after onboarding.

- NRR that struggles to reach 100%: expansion isn’t offsetting churn and downgrades, so growth depends on constant new acquisition.

- Activation is fragile: success requires heroic support or founder involvement every single time.

- Sales is “custom-building” every deal: if every demo promises a different product, your roadmap becomes a hostage negotiation.

- CAC payback feels like a slow leak: you’re spending today to maybe recover the money next yearif customers don’t churn first.

- Support volume scales faster than revenue: your product complexity is growing faster than customer value.

A simple test: “Would you buy more of your own growth?”

If your growth depends on founder rescue missions, big discounts, and custom promises, you’re not scaling. You’re sprinting while carrying a couch.

The fix: stop pouring gaspatch the bucket

The best teams don’t “choose” between growth and retention. They sequence them. They earn growth by making retention inevitable.

Step 1: Pick an ICP like it’s a marriage, not a dating app

Most early SaaS pain comes from serving too many “kinds” of customers. You can’t be the perfect tool for everyone. But you can be the obvious choice for someone.

Actions that help fast:

- Identify the segment with the strongest retention and shortest time-to-value.

- Double down on the use cases that create habitual usage.

- Stop building for “edge-case whales” that pull you off strategy (even if they have a big logo).

Step 2: Make onboarding boringly effective

Great onboarding is not “a tour.” It’s a guided path to value.

Reduce friction, shorten setup, and help customers reach an outcome quickly. If users need a PhD in Your Product to succeed, you’re not building SaaSyou’re building a puzzle box.

Practical upgrades:

- Define an “activation event” (the moment users experience real value) and optimize the path to it.

- Reduce the number of required steps to get there.

- Use templates, defaults, and examplesespecially for B2B workflows.

Step 3: Measure retention in cohorts, not vibes

Retention is the “truth serum” metric. Track it by cohort (signup month, plan type, acquisition channel, customer segment) so you can see what’s improvingand what’s quietly on fire.

Ask churned customers one question: “What job were you hiring us to do, and what made us fail at it?” Then treat the answers like your next roadmap sprint depends on it… because it does.

Step 4: Fix pricing without turning into a discount factory

Pricing problems often masquerade as “sales problems.” The classic move is discounting to close deals. It feels like progress until the unit economics show up with a baseball bat.

Better moves:

- Align packaging to the value customers actually get (not just seats because “that’s what SaaS does”).

- Make expansion natural: usage-based, capacity-based, or outcome-linked models can work when they reflect real value.

- Use incentives that support retention (annual plans, onboarding support, success milestones), not desperation discounts.

Step 5: Then scaleonce the engine is repeatable

When you see retention stabilize and newer cohorts perform better than older ones, scaling becomes less risky and more math-driven.

At that point, hiring and spending don’t feel like a gamble. They feel like turning up the volume on a song people already love.

Three concrete examples (anonymized, but painfully real)

Example 1: “We hired 8 SDRs… and taught them to sell a moving target”

A B2B tool saw early inbound interest from several industries. Instead of choosing, they pursued all of them. Each salesperson learned a different pitch. Product built “just one more feature” for each deal. Support became a trauma unit.

Fix: they narrowed to one ICP where retention and expansion were strongest, standardized the demo, rebuilt onboarding around that segment’s workflow, and reduced custom work. Pipeline got smallerbut close rates, retention, and referrals rose.

Example 2: “Marketing worked. The product didn’t.”

A PLG SaaS company drove signups through content and paid search. Activation was low, churn was high, and the team kept increasing ad spend to compensate.

Fix: they paused spend increases and focused on time-to-value: fewer setup steps, better defaults, and clearer “next best action” prompts. Signups stayed flat, but paid conversions and retention improvedso revenue climbed without needing more traffic.

Example 3: “Discounts closed deals… and quietly killed LTV”

A sales-led SaaS company used heavy discounting to hit quarterly targets. Customers who demanded discounts tended to churn faster and expand less. The company “won” revenue that didn’t stick.

Fix: they tightened discount rules, improved onboarding and success milestones, and reworked packaging to match value. Deals closed a bit slower, but churn improved, support costs dropped, and expansion became real.

A practical checklist to avoid the “biggest SaaS mistake”

- Before hiring aggressively: confirm retention and activation are improving for new cohorts.

- Before increasing spend: make sure onboarding reliably produces “aha” moments.

- Before expanding markets: win a narrow beachhead and document what “repeatable” looks like.

- Before building new features: ask whether it improves retention for your best-fit segment.

- Before discounting: ask what problem you’re trying to paper over (positioning, pricing, trust, onboarding, missing capability).

Conclusion: the biggest SaaS mistake is skipping the hard part

Scaling is the fun partheadcount, press releases, dashboards that go up and to the right. But SaaS winners earn growth by doing the unsexy work first: retention, onboarding, clarity on who the product is for, and a go-to-market motion that’s repeatable.

If you remember one thing, make it this: Growth doesn’t fix product-market fit. Product-market fit makes growth safer.

500+ words of “I’ve seen this movie before” experiences (and how it usually ends)

I’ve watched SaaS teams do the premature-scaling dance in more variations than a streaming service has crime documentaries. The pattern is weirdly consistent.

First comes the early “signal”: a handful of customers love the product. Maybe they’re power users. Maybe they’re unusually motivated. Maybe they’re friends-of-friends who desperately needed exactly what you built. The team feels momentum, so they assume they’ve unlocked the market.

Then comes the translation error: the company treats “some people love us” as proof that “many people will love us.” That’s when the hiring plan gets bold. A sales leader arrives with a big playbook. Marketing ramps. New tools get bought. A fancy attribution dashboard gets installed (which, to be fair, is a rite of passage).

And suddenly, the company is spending real money to scale something that still requires founder-level intuition to make customers successful. The sales team starts selling promises instead of outcomes because deals must close. The product team gets pulled into high-pressure, one-off requests because the pipeline depends on it. Customer success becomes a patch crew racing from one onboarding fire to the next.

One of the most common “tell” is what happens in internal meetings. If every revenue conversation includes phrases like “we can build that quickly” or “we’ll handle it manually for now” or “we just need more top-of-funnel,” you can practically hear the bucket leaking.

I’ve also seen the emotional side: teams confuse motion with progress. They’re busy. They’re shipping. They’re running campaigns. They’re hiring. But retention doesn’t improve, which means the company is running faster on the same treadmill. Eventually, the burn rate becomes the villain in the story.

The “happy ending” version is when leadership has the courage to slow down. They stop chasing every customer type. They pick an ICP and commit. They redesign onboarding so success isn’t a heroic eventit’s a predictable path. They measure cohorts and learn which behaviors actually correlate with renewals and expansion. They fix pricing so it reflects value instead of panic. And thenonly thengrowth becomes something you can invest in with confidence.

The “sad ending” version is when the company doubles down on scaling as the solution to scaling problems. That’s when you see layoff cycles, pivot whiplash, and teams rebuilding trust with customers who felt like beta testers. The tragedy isn’t that the product was bad. The tragedy is that the company never gave itself the space to make the product truly stick before flooring the gas pedal.

If you want a simple takeaway from all those experiences, it’s this: the best growth hack is a product that customers don’t want to leave.