Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The headline is dramaticso what does “1.6 years” actually mean?

- What the study found (and what it didn’t)

- Why might sweeteners affect brain health? The leading theories

- The biggest asterisk: observational studies are messy (and reality is messier)

- How this fits into the bigger picture: safety vs. “optimal”

- Practical takeaways: how to be smart (not scared) about sweeteners

- What researchers still need to figure out

- Real-world experiences (extra ): what people notice when they cut back

Diet soda has always felt like the life hack of the beverage aisle: all the sweetness, none of the sugar, and a can that hisses like it’s opening a portal to “better choices.” But a new study is asking an awkward question: what if “sugar-free” comes with a hidden price tagpaid in memory and mental sharpness?

Researchers reported that people who consumed the highest amounts of certain low- and no-calorie sweeteners experienced faster declines in thinking and memoryan effect the authors translated as being equivalent to about 1.6 years of cognitive aging. Before anyone panic-throws their sweetener packets into the sea: this was an observational study, meaning it found an association, not proof of cause-and-effect.

Still, the headline is sticky (ironically), and the topic matters. Artificial sweeteners and sugar alcohols are everywherediet drinks, “zero sugar” snacks, sugar-free yogurt, protein bars, gum, flavored waters, and that mysterious “keto” ice cream that tastes like dessert and a chemistry quiz at the same time.

Note: This article is for general education, not medical advice. If you have diabetes or health conditions and want personalized guidance, a clinician or registered dietitian can help you decide what’s right for you.

The headline is dramaticso what does “1.6 years” actually mean?

Let’s translate the translation. The study didn’t take a brain scan and print out a receipt that said, “Congratulations, your brain is 1.6 years older.” Instead, researchers followed people over time and measured changes in performance on cognitive tests (memory, language, processing speed, and more). Then they compared the rate of cognitive decline between groups with different sweetener intakes.

When scientists say the difference is “equivalent to 1.6 years of aging,” they’re taking the statistical gap in cognitive scores and mapping it onto the typical decline you might expect with aging over that time span. It’s a way of making numbers feel human-sized. Helpful for understanding, but easy to misread as a literal “brain age” label.

What the study found (and what it didn’t)

Who was studied?

The researchers analyzed data from 12,772 adults in Brazil, with an average age around the early 50s, followed for about eight years. Participants completed dietary questionnaires, and they took a battery of cognitive tests multiple times over the study period.

Which sweeteners were included?

The study tracked a mix of commonly used low- and no-calorie sweeteners, including:

- Aspartame

- Saccharin

- Acesulfame potassium (Ace-K)

- Erythritol (a sugar alcohol)

- Xylitol (a sugar alcohol)

- Sorbitol (a sugar alcohol)

- Tagatose (a sweetener that, interestingly, did not show the same association in this analysis)

How much sweetener counted as “high” intake?

Participants were grouped by estimated daily intake. The highest-consumption group averaged about 191 mg per day of total sweetenersan amount the researchers compared to roughly one can of diet soda worth of aspartame (as a practical reference point). The lowest group averaged around 20 mg per day.

What changed over time?

After adjusting for various factors (such as age, sex, and some health conditions), the highest intake group showed a faster decline in overall thinking and memory. Reported another way: their global cognitive decline was about 62% faster than the lowest intake grouptranslated as about 1.6 years of additional cognitive aging. The middle intake group also showed faster decline (often described as roughly 1.3 years in the same style of translation).

Two results stood out:

- Age mattered: The association was seen more clearly in adults under 60, and it wasn’t observed the same way in people 60+ in this dataset.

- Diabetes status mattered: The link between sweetener intake and cognitive decline appeared stronger in participants with diabetes (who may also be more likely to use sweeteners as sugar substitutes).

Important: the study design cannot prove that sweeteners caused the decline. It can only say higher intake traveled alongside faster decline in this population.

Why might sweeteners affect brain health? The leading theories

Scientists are still connecting dots, but several plausible pathways are being explored. Think of these as “mechanism candidates,” not courtroom verdicts.

1) The gut-brain connection

Your gut isn’t just a food tubeit’s a chemical messaging center. Some research suggests certain non-nutritive sweeteners may influence the gut microbiome, which can affect inflammation, metabolism, and signaling to the brain. If the microbiome shifts in an unfavorable way, it could theoretically nudge cognitive health over the long term.

2) Metabolic signaling and “sweetness without sugar” confusion

Sweet taste is a signal. When sweetness repeatedly arrives without calories (or arrives with different metabolic effects), researchers wonder whether it may alter appetite regulation, cravings, or glucose and insulin responses in some people. The brain is an energy-hungry organ, and long-term metabolic changes can matter for cognitive aging.

3) Vascular function and oxidative stress

Brain health depends heavily on healthy blood vessels. Separate lines of evidence (not the same as this cognitive study) have raised questions about certain sugar alcoholslike erythritoland potential effects on vascular biology in lab or clinical contexts. These findings don’t automatically apply to everyday consumption for everyone, but they add to a larger “we should keep studying this” file.

The biggest asterisk: observational studies are messy (and reality is messier)

Observational research is valuableespecially when randomized trials would be expensive, long, and ethically complicated. But it comes with built-in limitations:

- Self-reported diet isn’t perfect. People forget, misestimate portions, and don’t always know what’s in processed foods.

- Confounding is real. High sweetener intake may cluster with other factors that affect cognition (overall ultra-processed food intake, stress, sleep, activity levels, cardiometabolic health, and more).

- Reverse causation is possible. People already on a health journeyor with early metabolic issuesmay switch to “sugar-free” products, which can make sweeteners look guilty even if they’re more like the bystander at the scene.

This is why the most responsible interpretation is: heavy use of certain low- and no-calorie sweeteners may be a marker of riskor a contributor to riskand we need more research to separate the two.

How this fits into the bigger picture: safety vs. “optimal”

In the U.S., several high-intensity sweeteners are FDA-approved for use in foods, which means they’ve been evaluated for safety within established limits. That’s a crucial point: “approved as safe” generally refers to toxicology and acceptable daily intakenot a promise that frequent use improves long-term health outcomes for every person in every context.

Major health organizations have taken a measured approach. For example:

- Some guidance recognizes that swapping sugar-sweetened beverages for low-calorie sweetened options may help reduce added sugar intake for certain people.

- At the same time, many experts emphasize that water and unsweetened beverages are the gold standard, and that relying on sweetnesswhether from sugar or substitutescan keep preferences locked on “dessert mode.”

Also, this isn’t the first time artificially sweetened drinks have been linked (in some studies) to brain-related outcomes. A well-known cohort analysis from the Framingham Heart Study previously reported associations between artificially sweetened beverages and risks like stroke and dementia. Those findingslike this new workwere observational and sparked debate about confounding and causality. The pattern across studies is less “case closed” and more “pattern detectedinvestigate further.”

Practical takeaways: how to be smart (not scared) about sweeteners

If you use artificial sweeteners, you don’t need to treat your pantry like a crime scene. But you can make choices that reduce potential downsidewithout turning your life into a joyless spreadsheet.

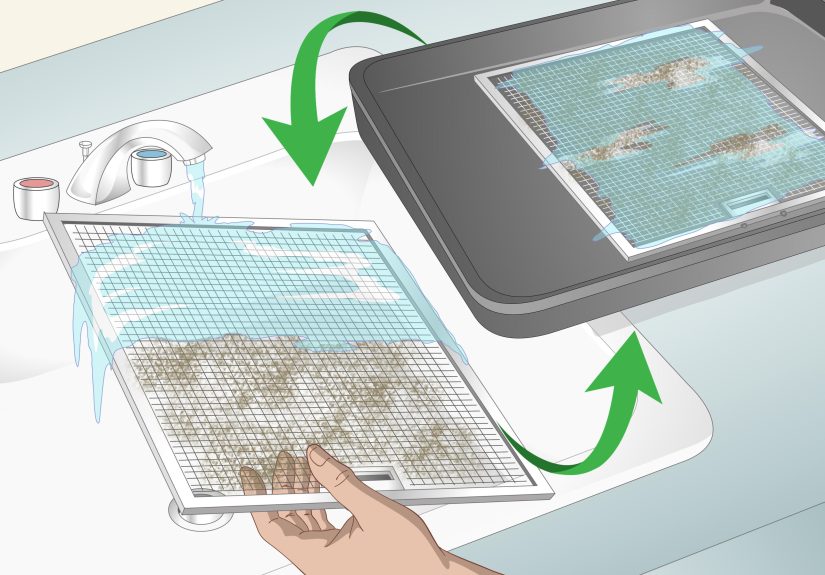

1) Check where sweeteners are sneaking in

Many people think “I only use one packet in coffee,” while forgetting the diet soda at lunch, the sugar-free gum, the “zero sugar” yogurt, and the protein bar that tastes suspiciously like birthday cake. Scan labels for ingredients like aspartame, saccharin, sucralose, Ace-K, erythritol, xylitol, and sorbitol.

2) Aim to reduce your overall “sweetness dependence”

The brain adapts. Many people find that when they gradually reduce sweeteners, their taste buds recalibrate and foods like fruit start tasting sweeter again. Try stepping down slowly: half the sweetener, fewer sweetened drinks per week, or mixing flavored sparkling water with plain.

3) Prioritize beverage upgrades first

Beverages are the easiest place to rack up sweeteners without noticing. Consider rotating in:

- Water (sparkling or still)

- Unsweetened tea (hot or iced)

- Coffee with cinnamon or vanilla extract instead of extra sweetener

- Infused water (citrus slices, mint, cucumber)

4) If you have diabetes, don’t go roguego strategic

Many people with diabetes use sweeteners to reduce added sugars, and that can be a helpful tool. But this study suggests a reason to avoid assuming “more is automatically better.” The goal isn’t to swap unlimited sugar for unlimited substitutesit’s to improve overall diet quality, cardiometabolic health, and consistency. If you’re making changes, consider doing it with professional guidance tailored to your blood glucose goals.

5) Remember: “sugar-free” doesn’t always mean “health-forward”

Ultra-processed foods can be ultra-processed even when they’re sugar-free. A “zero sugar” cookie is still a cookie. The best long-term brain-health pattern is usually built on minimally processed foods: vegetables, fruit, legumes, whole grains, nuts, quality proteins, and healthy fatsplus sleep, movement, and social connection.

What researchers still need to figure out

This study is a strong signal, but it’s not the final word. Future research will be most useful if it can:

- Separate the effects of specific sweeteners (since they’re not all chemically similar).

- Measure intake more precisely over time (not only by questionnaire).

- Use additional brain-health markers (imaging, inflammation markers, vascular measures).

- Test “sweetener reduction” interventions to see whether cognition changes.

Until then, a practical middle path makes sense: enjoy sweetness sometimes, but don’t outsource your entire flavor life to sugar substitutes.

Real-world experiences (extra ): what people notice when they cut back

Let’s talk about the part that never makes it into the abstract: how this plays out in regular life, where your brain is juggling school pickups, deadlines, and the eternal mystery of where all the phone chargers go. When people hear “artificial sweeteners may age the brain,” the first reaction is often either panic or dismissal. But in everyday routines, the sweetener story tends to be less dramaticand more revealing.

Experience #1: The “one diet soda” that was actually three. A lot of folks discover that sweeteners aren’t a single choicethey’re a pattern. Someone may start with one diet soda at lunch, then add a “zero sugar” energy drink on busy mornings, then finish with sugar-free dessert because it feels like a free pass. When they total it up, the surprise isn’t “I use sweeteners,” it’s “I use sweeteners constantly.” The first shift that feels meaningful is simply noticing where the sweeteners are coming from.

Experience #2: Taste buds renegotiate the contract. People who reduce sweeteners often report a weird week or two where everything tastes less exciting. (Your palate is basically filing a complaint.) Then something funny happens: fruit tastes sweeter, plain yogurt tastes less bland, and coffee starts to feel drinkable without being dessert-in-a-mug. It’s not magicit’s adaptation. Your “sweet threshold” can change when sweetness is less frequent.

Experience #3: Cravings can changesometimes in either direction. Some people notice fewer cravings when they cut back, especially if diet drinks were tied to snacking triggers. Others notice the opposite at first: “If I can’t have my sweet drink, I want candy.” This is where strategy helps. Replacing a sweetened beverage with something you actually enjoysparkling water with lime, iced tea, or coffee with spicescan keep the habit loop (sip + satisfaction) without the same sweet intensity.

Experience #4: The label game is exhausting, so people simplify. After a while, many people stop trying to micromanage individual sweeteners and focus on a simpler rule: fewer ultra-processed “diet” products overall, more whole foods, and sweetness as an occasional guestnot a roommate. This approach also reduces decision fatigue, which is very underrated as a brain-health strategy.

Experience #5: “Moderation” becomes more concrete. Moderation isn’t a personality trait; it’s a setup. People have more success when they build a default routine (water/unsweetened beverages most of the time) and then choose sweetened items intentionallylike a diet soda with a specific meal instead of an all-day companion. The result is often less about “perfectly avoiding sweeteners” and more about feeling in control of the pattern.

If this study motivates one practical experiment, make it this: for two weeks, keep sweetenersbut make them less automatic. Track where they show up, reduce the easiest source first (usually beverages), and see what changes in energy, cravings, and focus. Not because you’re chasing perfectionbecause your brain deserves data that’s personal, not just headlines.