Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why 1996 Matters: The “Warning That Didn’t Work” (Until It Did)

- Why 1999 Matters: When the Narrative Starts Driving the Car

- So What’s Different Today? Profits, Giants, and the “Real Business” Problem

- The AI Capex Arms Race: Today’s “Picks and Shovels,” Yesterday’s Fiber

- Valuations, Concentration, and the “Is Everyone on the Same Trade?” Issue

- The Speculation Meter: How to Tell When Froth Is Spreading

- Is It 1996 or 1999? A Practical Checklist (No Crystal Ball Required)

- 1) Are profits realand improving?

- 2) Are expectations realisticor magical?

- 3) Is capex being funded sustainably?

- 4) Is the market broadening or narrowing?

- 5) Is speculation containedor contagious?

- 6) Are investors allergic to risk management?

- 7) If the market dropped 30% tomorrow, would your plan survive?

- What the 1996-to-1999-to-Afterward Story Teaches (Without Demanding Perfect Timing)

- Conclusion: The Market’s Real Trick Is That It Can Be Both

- Experiences Related to “Is This 1996 or 1999?” (Real-World Investor Moments)

Imagine you walk into the stock market and it hands you a name tag that says: “Hi, I’m the Future.”

Then you glance down and realize the tag is written in Comic Sans, sprinkled with rocket emojis, and smells faintly of

“just one more valuation multiple.” That’s when the big question shows up:

are we living in 1996early in a powerful runor 1999late enough that the party has

started serving dessert for dinner?

Ben Carlson’s “Is this 1996 or 1999?” frames the dilemma perfectly: markets can look “toppy,” get even more “toppy,”

and still keep climbing for longer than your patience (and your group chat) can survive. The point isn’t to predict

the exact day the music stops. The point is to understand what’s happening on the dance floor, so you don’t do the

financial equivalent of attempting a backflip in flip-flops.

This article takes that time-travel question seriouslywithout taking ourselves too seriously. We’ll revisit what made

the late 1990s feel like the late 1990s, compare it to today’s AI-and-mega-cap-driven market, and lay out a practical

way to think about bubbles, valuations, and staying sane when everyone else is acting like a chart is a personality.

Why 1996 Matters: The “Warning That Didn’t Work” (Until It Did)

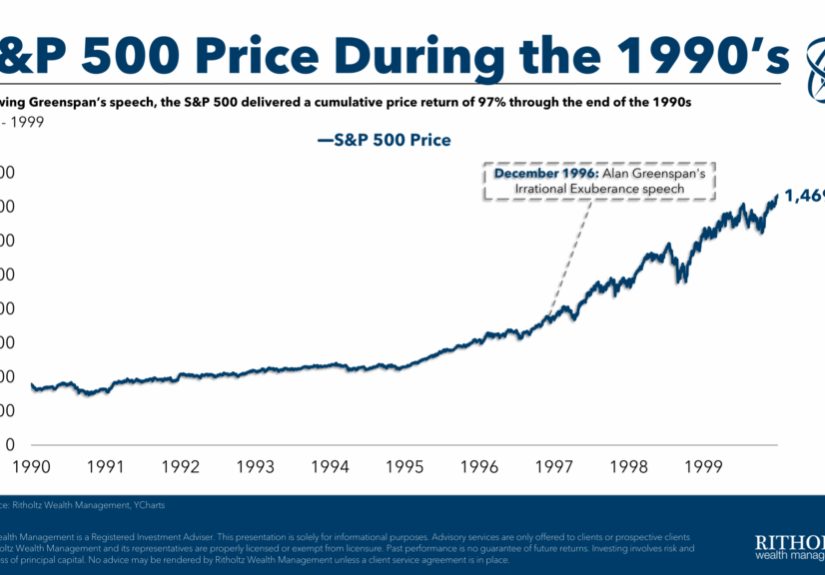

In December 1996, Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan delivered remarks that would become legendary for one loaded

phrase: “irrational exuberance.” His broader message wasn’t “sell everything and move into a cabin.”

It was more like: “Asset prices can get disconnected from reality, and central bankers should pay attention.”

The problem (for market timers) is that attention does not come with a stopwatch.

What happened next is the part that makes history such a mischievous teacher:

the market kept rising. A lot. Enough that anyone who tried to “front-run the crash” in 1996 probably

spent the next few years watching friends brag at barbecues like they personally invented the internet.

1996 as a market mood

Think of 1996 as a stage where optimism is growing but still has plausible “grown-up” explanations:

inflation is relatively contained, productivity narratives sound credible, and the new technology story is realeven if

the market is getting ahead of itself. People feel excited, but many still pretend they’re “long-term investors” while

checking prices every 11 minutes.

Why 1999 Matters: When the Narrative Starts Driving the Car

By 1999, the dot-com era wasn’t just optimism. It was confidence cosplay.

The vibe shifted from “this technology will change the world” to “this technology will change the world by Tuesday,

and also profits are optional now.”

This is typically what late-stage mania looks like:

valuations stretch beyond historical comfort zones, “story stocks” multiply, and funding flows toward anything that can

be explained with a futuristic sentence and a slick logo. Markets also get more crowded at the topbecause the

biggest winners become the default destination for investor dollars.

The telecom buildout: the underappreciated cousin of the dot-com bubble

One of the most useful parallels for today isn’t just “dot-com stocks.” It’s the massive

telecommunications infrastructure buildout that expanded fiber networks and capacity ahead of demand.

The logic sounded flawless: internet usage is exploding, so we need to build the pipes now.

The outcome was messier: capacity surged, pricing pressure hit, and several businesses learned the hard way that

“demand will grow eventually” can be a brutal investment thesis if you run out of cash first.

This matters because bubbles don’t always die from one dramatic pop.

Sometimes they die from oversupply, thinner margins, and disappointed expectations.

The future arrives… just not fast enough to justify the bill.

So What’s Different Today? Profits, Giants, and the “Real Business” Problem

If you compare 1999 to today, you’ll quickly notice a key difference:

many of today’s market leaders are highly profitable, entrenched businesses with global scale.

Late-1990s hype often floated companies with little revenue, thin moats, and business models that depended on

“first-mover advantage” staying loyal forever.

Today’s largest tech and tech-adjacent firms tend to have:

- Real cash flow (not just “potential” cash flow)

- Durable distribution (platforms, ecosystems, default behaviors)

- High margins (which make big investments easier to fund)

- Pricing power (at least more than Pets.com ever dreamed of)

That doesn’t mean prices can’t get overheated. It means the “bubble debate” shifts from

“these businesses are fake” to “these businesses are real, but are investors paying too much for the future?”

The AI Capex Arms Race: Today’s “Picks and Shovels,” Yesterday’s Fiber

One of Carlson’s sharpest comparisons is the resemblance between the 1990s telecom buildout and today’s

AI capital expenditure (capex) surge.

Companies are spending staggering sums on data centers, specialized chips, networking, and energy infrastructure.

If the AI economy scales as fast as the most optimistic forecasts suggest, this capex looks visionary.

If adoption is slower, monetization is thinner, or competition commoditizes returns, the math gets uncomfortable.

Why capex booms feel irresistible

Capex booms are seductive because they sit at the intersection of three powerful forces:

the fear of missing out, the fear of being disrupted, and the fear of telling investors,

“Actually, we’re going to wait and see.” In a hot market, “wait and see” sounds like “we have no ideas.”

Where the risk hides

The risk isn’t simply “AI is fake.” The risk is that:

- Too many firms build too much capacity at once

- Costs (power, chips, construction, talent) rise faster than expected

- Customers demand AI features, but refuse AI pricing

- The competitive advantage of AI becomes table stakes rather than a moat

In other words: even if AI changes everything, the investors funding “everything” can still overpay for the privilege.

Valuations, Concentration, and the “Is Everyone on the Same Trade?” Issue

Asking “1996 or 1999?” isn’t just about headlines. It’s about market structure.

Two signals that often show up late in bull markets are:

elevated valuations and high concentration.

Valuation: not a timer, but a temperature

Measures like the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (CAPE) are often used as “expensive vs cheap” thermometers.

A high reading doesn’t tell you the market will crash next Tuesday. It tells you:

the market is pricing in a lot of good news, and future returns may depend on continued excellence.

Concentration: when leadership becomes dependency

In cap-weighted indexes, the biggest winners get bigger weightsmeaning more of your index return comes from fewer names.

That can be fine when leadership is broadening. It can be risky when leadership narrows, because the whole market starts

leaning on a handful of companies to deliver perfection.

Concentration also affects psychology. When a few stocks dominate the story, people stop asking,

“Is this a good portfolio?” and start asking, “Do I own enough of the stock?”

That’s not analysis. That’s an emotional support allocation.

The Speculation Meter: How to Tell When Froth Is Spreading

Another way to gauge “1996 vs 1999” is to look at speculative behavior across markets.

Speculation isn’t always badrisk capital can fund real innovation. The problem is when speculation becomes

a substitute for a business plan.

Common signs that the froth is rising:

- Hot issuance: waves of IPOs, trendy new listings, and “public market speedruns”

- Leverage creep: more borrowing, more derivatives, more “it can’t go down” trades

- Shortcut narratives: “profits don’t matter,” “this time is different,” “valuation is outdated”

- Copycat strategies: everyone chasing the same theme, factor, or trade

- Social proof: investing decisions outsourced to popularity

If this sounds familiar, it’s because markets have a long history of recycling the same human behavior under new branding.

The tech changes. The emotions don’t.

Is It 1996 or 1999? A Practical Checklist (No Crystal Ball Required)

Instead of trying to predict the peak, ask questions that help you understand where risk is building.

Here’s a framework you can actually use:

1) Are profits realand improving?

In 1999, many businesses were “future profitable.” Today, many leaders are profitable now.

That’s a meaningful difference. But it doesn’t eliminate valuation risk.

2) Are expectations realisticor magical?

The most dangerous sentence in markets is: “Growth will be huge forever, and competition won’t matter.”

3) Is capex being funded sustainably?

Big investments can be smart. They can also be forced by fear. Watch whether spending is supported by

long-term demand signals or justified mainly by “we can’t be left behind.”

4) Is the market broadening or narrowing?

A healthy bull market usually spreads leadership over time. A fragile one depends on a short list of heroes.

5) Is speculation containedor contagious?

When speculation spreads from niche corners into “normal” portfolios, you’re closer to 1999 energy.

6) Are investors allergic to risk management?

Late-cycle behavior often includes mocking diversification, dismissing bonds or cash as “dead,”

and treating volatility as a personal insult.

7) If the market dropped 30% tomorrow, would your plan survive?

This question is the grown-up version of “Are we in a bubble?” Because your outcomes depend less on labels

and more on whether you can stay invested when the headlines get dramatic.

What the 1996-to-1999-to-Afterward Story Teaches (Without Demanding Perfect Timing)

One of the most humbling lessons from the late 1990s is that you could have invested in 1996 (after the warning),

lived through the boom, survived the bust, and still ended up with a respectable long-run resultif you stayed

invested and didn’t treat a bear market like an eviction notice.

This is why long-term disciplines matter more than “being right” about the era.

Tools like diversification and steady investing over time can reduce the damage of bad timing.

Dollar-cost averaginginvesting a fixed amount at regular intervalscan help investors avoid the emotional trap of

trying to pick the perfect day.

Important note (especially for younger readers): this is educational, not personal financial advice.

Real-life investing decisions depend on your situation, your time horizon, and your risk tolerance.

If you’re not sure, talk with a trusted adult or a qualified professional before acting.

Conclusion: The Market’s Real Trick Is That It Can Be Both

The honest answer to “Is this 1996 or 1999?” is frustratingly human:

parts of the market can feel like 1996 and 1999 at the same time.

You can have real innovation, real profits, and real long-term value creation

alongside pockets of overheated pricing, crowding, and speculative behavior.

The goal isn’t to win the time-travel trivia contest. The goal is to build a plan that doesn’t depend on you guessing

which year it is. Because if history is any guide, the market won’t send a calendar invite when it changes moods.

Experiences Related to “Is This 1996 or 1999?” (Real-World Investor Moments)

When people talk about “1996 vs 1999,” they’re usually describing an experience more than a statistic: the feeling of

standing in a fast-moving crowd and trying to decide whether you’re witnessing the beginning of something historic or

the end of something overheated. Those experiences show up in patterns that repeat across generations.

One common experience is the slow shift from curiosity to certainty. Early on, investors hear about a

new technologysay, the commercial internet in the 1990s or generative AI todayand they’re curious. They read, they

learn, they buy a little, and they expect bumps along the way. But as prices keep rising, curiosity often morphs into

certainty: “It’s going up because it’s the future.” That’s the moment the story starts doing more work than the numbers.

People stop asking, “What would need to be true for this valuation to make sense?” and start asking, “How much can I

buy before it goes even higher?”

Another repeating experience is the social pressure of a winning market. In a strong bull run,

investing becomes dinner conversationeven among people who previously swore they “don’t do stocks.” You’ll hear stories

about a friend of a friend who doubled their money “in a month,” or someone who discovered a “guaranteed” strategy that

somehow involves both leverage and confidence. This is where the market starts to feel like a scoreboard for identity:

being invested becomes a proxy for being smart, modern, and ahead of the curve. That’s also when it becomes hardest to

admit uncertaintybecause uncertainty feels like losing.

Many investors also describe a third experience: the confusion of good news that doesn’t help.

In late-stage markets, you can get genuinely positive developmentsreal products, real customers, real breakthroughs

and still see prices fall. Why? Because the market wasn’t pricing “good.” It was pricing “perfect.”

When expectations get too high, reality can arrive and still disappoint. People who lived through the dot-com era often

remember that the internet absolutely changed the worldyet many internet-era stocks still collapsed because the prices

assumed a future that was too big, too fast, and too profitable all at once.

There’s also the experience of realizing that timing feels easy only in hindsight.

In the moment, the market doesn’t announce, “Welcome to 1999!” It just keeps rewarding risk-takinguntil it doesn’t.

That’s why many long-term investors talk less about predicting tops and more about building a routine they can stick

with. The people who come out okay often aren’t the ones who called the peak. They’re the ones who sized risk sensibly,

diversified, kept adding over time, and avoided decisions that required them to be perfect under stress.

Finally, a surprisingly common experience is emotional whiplash: regret in both directions.

If you stay cautious and the market keeps rising, you regret not buying more. If you chase and the market drops, you

regret buying at all. This is the psychological trap that makes the “1996 or 1999” question so sticky.

It isn’t just about returns; it’s about wanting to feel like your choices make sense.

The healthiest investors tend to accept that regret is part of the processand they design their approach so they don’t

have to “win” every year to succeed over decades.

In that sense, the best takeaway from the 1996 vs 1999 comparison is not a prediction. It’s permission:

permission to admit uncertainty, to avoid hero bets, and to prioritize a plan that works even when the market acts like

it’s wearing a time machine and refusing to tell you the destination.