Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Meet the Shipwreck: Why the SS Thistlegorm Matters

- So What Is the VR Program, Exactly?

- What You’ll See on the Virtual Dive

- Why VR Shipwreck Tours Are More Than a Cool Tech Flex

- The Bigger Trend: VR, Museums, and the Rise of Digital Heritage

- How to Try a WWII Shipwreck VR Experience Without Overcomplicating It

- What This Kind of VR Teaches That Textbooks Can’t

- Conclusion: A Dive You Can Take Without Getting Wet

- Extra: What the Experience Feels Like ( of “Virtual Dive” Vibes)

- SEO Tags

There are two kinds of people in the world: the “I could totally scuba dive” crowd, and the “I get winded opening a jar” crowd.

Both groups can now do something that used to require dive training, specialized gear, and a comfort level with deep water that not everyone has:

explore a real World War II shipwreck in virtual reality.

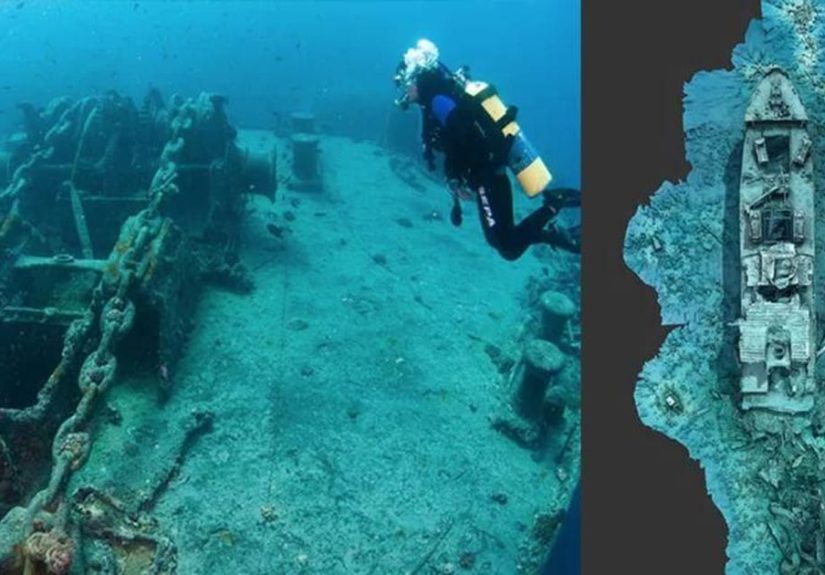

The star of this story is the SS Thistlegorm, a British merchant vessel sunk in 1941 in the Red Seanow considered one of the most famous wreck dives on Earth.

The VR experience, known as the Thistlegorm Project, stitches together an ultra-detailed 3D model of the wreck with immersive 360° underwater video.

Translation: you can “dive” the site from your living room, without needing a wetsuit, a regulator, or a friend named “Tank Guy Dave.”

Meet the Shipwreck: Why the SS Thistlegorm Matters

The SS Thistlegorm wasn’t a luxury liner or a battleship built for headlines. It was a working cargo shippart of the wartime logistics machine that kept the Allied effort moving.

When it went down, it took a jaw-dropping cargo with it: vehicles, supplies, and equipment meant for a massive campaign stretching across North Africa and the Middle East.

Today, divers know it as a time capsuleone that also deserves respect, because every wreck tied to war carries human stories, not just cool artifacts.

That human side matters a lot. Wartime merchant sailors faced terrifying risk while doing essential workdelivering supplies under threat of submarines, air raids, and mines.

It’s easy to focus on the dramatic images of sunken motorcycles and trucks, but the deeper point is that these ships represent service, sacrifice, and history that can’t be replaced once damaged.

The more people can learn about that legacy, the more likely it is to be protected.

So What Is the VR Program, Exactly?

The Thistlegorm Project is an online virtual experience built from two main ingredients:

photogrammetry (a method that turns thousands of overlapping photos into a measurable 3D model) and 360° video that puts you “in the water.”

Instead of a cartoonish recreation, you’re navigating a data-based digital twinan experience designed to look like the real wreck as it exists on the seafloor.

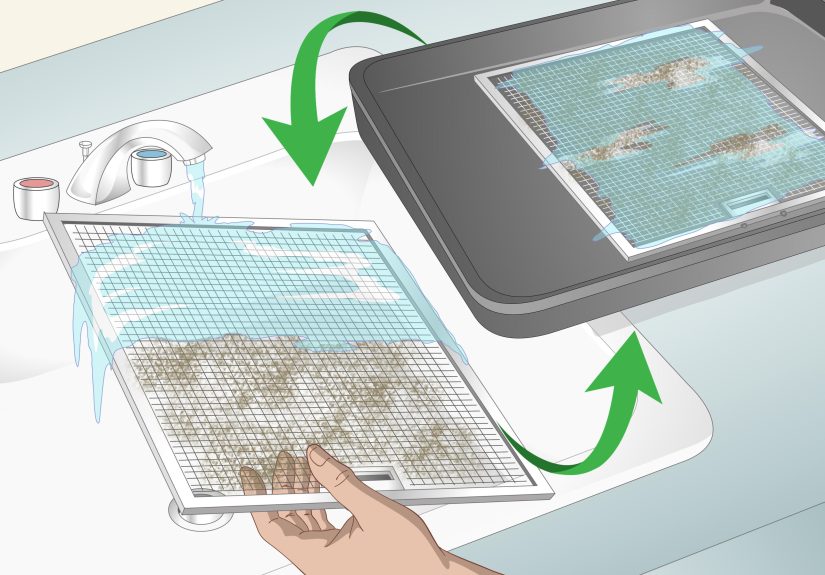

Ingredient #1: Photogrammetry (AKA “Math, But Make It Gorgeous”)

Photogrammetry works by taking many photos from multiple angles and letting specialized software calculate depth and geometry from shared points.

In underwater archaeology, it’s become a game-changer because it documents fragile sites without physically disturbing themlike creating a snapshot in time you can revisit later.

U.S. cultural and ocean agencies have embraced similar techniques to map submerged sites and generate interactive 3D models that researchers and the public can explore noninvasively.

For the Thistlegorm Project, the approach went big: tens of thousands of images were used to build the model, capturing details across a large wreck site.

That scale is the pointbecause a shipwreck isn’t one object on a pedestal; it’s an entire environment, full of structure, cargo, and context that can be lost if you only document a few “highlight” areas.

Ingredient #2: 360° Underwater Video (The Closest You’ll Get to Bubble Sounds)

A 3D model can be incredibly accurate, but it can also feel a little “museum display” if you don’t sense the space around it.

That’s where the 360° video comes in. It adds that unmistakable underwater vibe: the light, the movement, the scale, the feeling that you’re hovering over something massive and real.

In practical terms, it’s also great for first-time usersbecause it provides orientation and “presence” before you start clicking around a 3D model like a curious raccoon with a new flashlight.

What You’ll See on the Virtual Dive

The Thistlegorm is famous in large part because its cargo is visually striking and historically specific.

You’re not looking at generic “old ship stuff.” You’re seeing the remnants of a wartime supply runvehicles, equipment, and materials frozen into an underwater scene.

It’s the kind of place where history feels less like a chapter title and more like a physical reality.

The VR experience typically highlights key sections of the wreck, guiding your attention to areas divers often talk about:

the ship’s overall structure, major holds, and sections where cargo is still visible.

You get the benefit of exploration without the typical limitations of a single diveno air supply ticking down, no current pushing you off course, no mask fogging at the worst possible moment.

Why VR Shipwreck Tours Are More Than a Cool Tech Flex

Access: You Don’t Need to Be a Diver to Learn From a Dive Site

Underwater cultural heritage is famously hard to access. By definition, it’s underwaterand often remote.

VR changes the audience from “people with dive certifications and travel budgets” to basically “anyone with a screen.”

That’s not just convenient; it’s a shift in who gets to experience history.

Students, older adults, people with disabilities, and the simply-not-a-fan-of-open-water population can all explore the same site in a meaningful way.

Preservation: Digital Documentation Helps Protect Fragile Sites

Shipwrecks can deteriorate due to storms, corrosion, marine growth, human contact, and accidental damage from visitation.

High-quality 3D documentation creates a baseline recordso changes can be tracked over time.

U.S. agencies and researchers use related 3D documentation and scanning approaches to monitor underwater sites and evaluate environmental impacts, because you can’t protect what you can’t measure.

There’s also an ethical win here: documenting and sharing a wreck digitally can reduce pressure on the physical site.

If more people can “visit” virtually, fewer people may feel the need to treat the real wreck like an underwater theme park.

And yes, that includes the temptation to touch, move, or “souvenir” something that absolutely should stay where it is.

The Bigger Trend: VR, Museums, and the Rise of Digital Heritage

The Thistlegorm Project fits into a growing movement: museums, universities, and public institutions building immersive experiences that let people explore real places and artifacts in digital form.

The Smithsonian, for example, has spent years expanding public access to 3D digitized objectsletting anyone examine items online in detail that would be hard (or impossible) to see in person.

When you combine that mindset with shipwreck documentation, you get something powerful: a museum without walls… and without oxygen tanks.

Meanwhile, ocean and park-focused organizations in the U.S. have been developing and sharing photogrammetry-based models of submerged sites for research, education, and monitoring.

These models are especially useful because they are noninvasive, repeatable, and shareableideal traits when the real “exhibit” is sitting underwater where it can’t be put behind glass.

How to Try a WWII Shipwreck VR Experience Without Overcomplicating It

One of the most refreshing parts of modern virtual heritage projects is how flexible they can be.

Depending on the platform, you may be able to explore via a standard web browser, a phone, or a VR headset.

If you do have a headset, you’ll get stronger immersionbut you can still learn a ton from a screen-based version.

Quick Tips for a Better (and Less Nauseating) Virtual Dive

- Start slow: Spend a minute orienting yourself before you “move” through the scene.

- Use a swivel chair: Turning your body (instead of a joystick) can feel more natural.

- Take breaks: If you feel woozy, pause. You’re exploring history, not trying out for astronaut training.

- Zoom in on details: The magic of 3D models is the ability to inspect small features you’d miss on a fast-moving dive.

What This Kind of VR Teaches That Textbooks Can’t

Reading about World War II logistics is important, but it can feel abstract: tonnage, routes, supply chains, strategic objectives.

A shipwreck makes it concrete.

When you see a real vessel that never completed its voyageand the equipment that went down with ityou understand “supply lines” as something physical, vulnerable, and costly.

You also gain a different kind of historical empathy.

A virtual experience won’t replicate the danger of wartime sailing, but it can remind you that history happened to real people in real environmentsnot in neat timelines.

That’s why virtual heritage matters: it creates emotional clarity without turning tragedy into entertainment.

Conclusion: A Dive You Can Take Without Getting Wet

The Thistlegorm Project-style VR experience is a clever blend of storytelling and science.

It uses photogrammetry to preserve detail, 360° video to create presence, and digital access to bring a historic site to people who might never otherwise see it.

The result is more than a tech demo: it’s a modern way to protect and share underwater historywhile encouraging respect for the people and events connected to it.

If you’ve ever wanted to explore a WWII shipwreck but didn’t love the idea of deep water, expensive travel, or breathing through a tube like a very calm elephant,

this is your moment. History is waiting. And in VR, it’s surprisingly easy to visitthen leave everything exactly as you found it.

Extra: What the Experience Feels Like ( of “Virtual Dive” Vibes)

The first thing you notice in a good shipwreck VR experience is the scale. On a regular screen, a wreck can look like a messy pile of metal.

In VRor even in a well-built interactive 3D viewyou finally understand: this was a huge working ship, and you’re not just “looking at it,” you’re occupying its space.

Your brain starts doing that delightful trick where it forgets you’re standing in your room and begins acting like you’re hovering over a real place.

Then come the detailsthose tiny, story-rich clues that make history feel personal.

You might linger on the outline of a hold, trace the edge of a structural beam, or zoom in on cargo that looks eerily recognizable.

It’s not the same as being a diver, but it has a unique advantage: you can stop and stare as long as you want.

No rushing back to a boat, no checking a gauge, no “we have to go up now” hand signals.

It’s like pausing a documentary at exactly the right frameexcept you can move your head and the scene moves with you.

Emotionally, it’s a strange mix of curiosity and quiet respect.

Shipwrecks are fascinating, sure, but in a WWII context you also feel the weight of what you’re seeing.

A vessel like the Thistlegorm wasn’t a tourist attraction when it sailedit was part of a dangerous job that mattered.

Even virtually, you get a sense of the ship as a workplace, a mission, and a memory.

That’s why the best experiences don’t lean on jump scares or “spooky underwater” clichés.

They let the site speak for itself.

You’ll also notice how VR changes the way you learn.

If someone tells you “this ship carried supplies,” your brain files it under “fact.”

But if you can visually explore the settingmove from one area to another, inspect what’s present, and understand how things relate in spaceyour brain files it under “experience.”

And experiences stick.

It’s the difference between memorizing a date and remembering a place.

Practically speaking, you might find yourself developing a “virtual diver” rhythm:

rotate slowly, zoom in, back up, re-center, and follow a path that feels natural.

Some people treat it like a guided tour; others wander like they’re in an underwater open-world game.

Either way, you end up doing something surprisingly meaningful: paying attention.

In a world designed to distract you every eight seconds, spending time with a single historical siteexamining it carefullyis almost rebellious.

And when you take the headset off (or close the tab), you’re left with the odd feeling that you visited somewhere you’ve never been.

Your feet never left the floor, but your mind did.

That’s the secret superpower of virtual heritage: it makes history feel closeclose enough to care aboutand that’s usually where preservation starts.