18 minutes ago

0

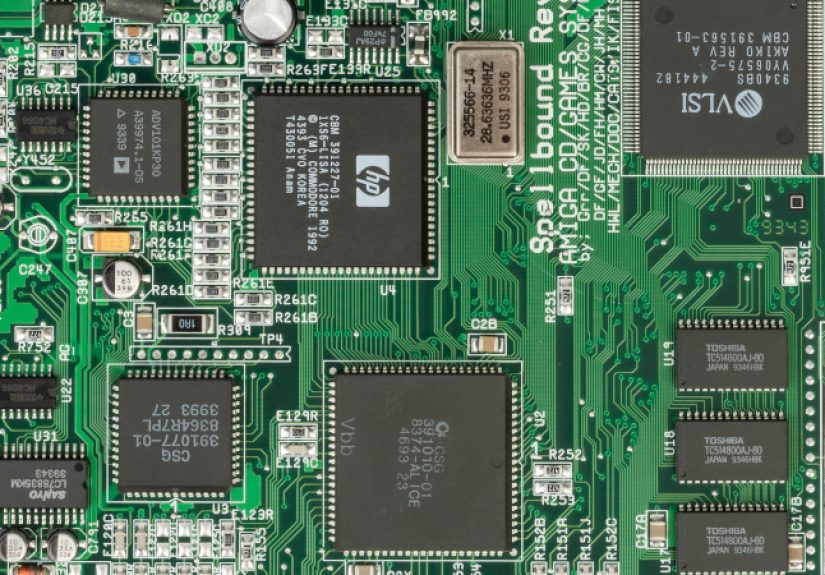

Lenovo’s Legion Go 2 has the kind of hardware that makes handheld PC gamers drool: a massive...