Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Castleford” Means (and Why It’s Complicated)

- The Material: Feldspathic Stoneware and the “Smear Glaze” Glow

- Design DNA: Silver-Shape Forms, Relief Panels, and Very Serious Lids

- Why Americans Fell for Castleford(-Type) Teapots

- How to Identify a Georgian Castleford Teapot (Without Becoming a Full-Time Detective)

- Castleford vs. “Castleford-Type”: A Practical Way to Talk About It

- Condition and Repairs: What People Check (Because 200-Year-Old Lids Have Lived a Life)

- Care and Use: Display Piece or Working Teapot?

- Decorating With a Georgian Castleford Teapot

- Common Misconceptions (Let’s Save You a Comment-Section Argument)

- Real-World Experiences With a Georgian Castleford Teapot ()

- Conclusion

If teapots could talk, a Georgian Castleford teapot would probably clear its throat politely, adjust its

neoclassical “waistcoat” of molded relief, and then bragjust a littleabout crossing the Atlantic when America was still

the new kid on the world stage. These pieces look refined, feel substantial, and come with one of the best party tricks in

antique ceramics: the famous sliding or hinged lid that makes collectors grin like they just found a secret door in a

library.

In this guide, we’ll unpack what “Castleford” really means, why the word can be both specific and frustratingly broad,

what makes these teapots “Georgian” in spirit (and often in date), and how to spot a great examplewithout needing a

monocle, a magnifying glass, and a dramatic violin soundtrack.

What “Castleford” Means (and Why It’s Complicated)

“Castleford” can refer to a real place and a real pottery: Castleford, Yorkshire, where a factory associated with

David Dunderdale & Co. operated in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, producing wares that included creamware,

black basalt, and white feldspathic stoneware. Museum records also note an important twist: many other English factories

made extremely similar wares, and today the label “Castleford” (or “Castleford-type”) is often used as a

generic term for a whole family of slip-cast, relief-molded, cream-to-white stoneware tea and table forms. In other words:

sometimes “Castleford” is a hometown, and sometimes it’s a vibe.

So is it “Georgian” or “Regency” or “Federal”… or all of the above?

The Georgian era broadly spans the reigns of the four King Georges (1714–1830). Many Castleford(-type) teapots

are commonly dated around 1790–1820, overlapping late Georgian and early Regency tastes: clean classical lines,

architectural panels, and ornament that looks borrowed from columns, cornices, and ancient friezesonly scaled down to

teapot size. When pieces include American patriotic motifs (eagles, seals, Liberty busts), you’ll also hear “Federal”

discussed in the U.S. contextbecause that’s the style moment these wares were feeding when they arrived stateside.

The Material: Feldspathic Stoneware and the “Smear Glaze” Glow

A signature of many Castleford-type teapots is white (or cream-toned) feldspathic stoneware. “Feldspathic” points

to a body rich in feldsparhelpful for achieving a pale, dense ceramic that can read almost porcelain-like at a glance,

but has its own personality: more grounded, often slightly warmer in tone, and typically heavier for its size.

Many examples are finished with a thin, glossy surface sometimes described as a smear glazea soft sheen that

can look like light is sliding across the surface (which is honestly perfect for a teapot that likes sliding parts).

Add in small touches of overglaze colorcommonly blues or greens used as trim lines and highlightsand you get a look

that’s crisp enough for formal tea, but not so fussy that it feels untouchable.

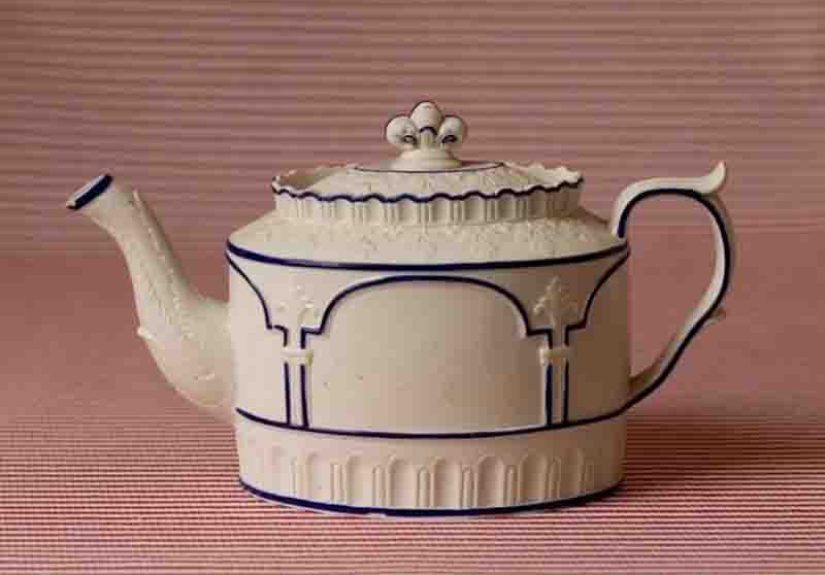

Design DNA: Silver-Shape Forms, Relief Panels, and Very Serious Lids

Castleford(-type) teapots often mimic “silver-shape” metalwork silhouettes: squared shoulders, baluster bodies,

octagonal or paneled sides, and handles that curve like they trained with a fencing coach. These were frequently made with

molds, which is why the decorative language tends to repeat in pleasing ways: reeding, acanthus leaves, lotus bands,

classical columns dividing panels, and little sprigged details that look like someone pressed a tiny botanical stamp into time.

The lid situation: hinged, sliding, and strangely satisfying

If you’ve ever lost a teapot lid (or watched one shatter in slow motion while you whisper “noooo”), you’ll appreciate this:

many Castleford-type designs used hinged covers held with a metal pin, or a sliding lid that tucks into a

guided opening. These mechanisms weren’t just cleverthey were practical for pouring during tea service, and they also

helped keep parts together in a world where “replacement lid” could mean “good luck, pal.”

Some lids are topped with finials shaped like flowers or pineapple-like forms. (Yes, pineapple. In the decorative arts,

pineapple is basically shorthand for “welcome, we have snacks.”)

Why Americans Fell for Castleford(-Type) Teapots

Here’s the plot twist that makes these objects feel like tiny time machines: many Castleford-type wares were exported, and

some were made for the American market with patriotic imagery. Museum and auction records describe pieces featuring

American eagles, the Seal of the United States, and even Liberty bust decoration. You can almost hear the

1800s marketing pitch: “It’s refined! It’s fashionable! It says ‘I’m worldly’ and also ‘USA’!”

A notable nuance from decorative-arts scholarship: the Castleford Pottery itself may not be firmly documented as producing

wares with American symbols, but the style was widely copied, and attributions can sometimes be made based on border

patterns and molded relief details. In other words, the design language became a kind of ceramic accentinstantly recognizable,

even if the speaker isn’t from the original hometown.

Spot-the-symbol: what patriotic motifs might look like

- Eagle with wings spread, often paired with shield elements

- Great Seal-style imagery, sometimes framed within a molded panel

- Liberty bust motifs on companion pieces in a teaset

- Stars and banners as supporting detail (sometimes referencing early U.S. symbolism)

How to Identify a Georgian Castleford Teapot (Without Becoming a Full-Time Detective)

The goal isn’t to “win” attribution in one afternoonit’s to understand what you’re looking at. Because “Castleford-type”

can cover several related makers and factories, identification is often about stacking clues rather than finding a single

magic stamp.

1) Start with the silhouette

Look for silver-inspired architecture: paneled sides, strong shoulders, and a shape that feels designed rather than

“freehand.” Many examples are oval, rectangular, baluster-shaped, or multi-sided.

2) Study the surface: body + glaze

Feldspathic stoneware tends to feel dense. The glaze can appear smooth and glossy, sometimes with that “smear” look.

The overall color often reads cream-white rather than bright paper-white.

3) Read the decoration like a map

Relief-molded panels separated by column-like dividers are common. Decorative bandsreeding, acanthus, lotus, small sprigs

often repeat around shoulder and base. Overglaze trim (blue, green) may highlight edges, finials, borders, and accent shapes.

4) Inspect the lid mechanics

Hinges and pins, or a sliding-lid design, are strong “family resemblance” indicators. Be cautious, though: lids can be replaced,

repaired, or married to the wrong body over centuries of household life.

5) Flip it over (carefully) and look for marks or numbers

Some examples show impressed numbers on the base. Museums record instances of small impressed numerals (like “20” or other

numbers) that may relate to factory systems or patterns. Marks can be absent even on authentic period pieces, so treat a blank

base as “inconclusive,” not “guilty.”

6) Compare with documented museum forms

When you can match a handle profile, spout shape, panel count, and the specific border pattern to a museum example, you’re

doing the kind of evidence-based comparison that professionals use (just with better snacks).

Castleford vs. “Castleford-Type”: A Practical Way to Talk About It

If you’re writing, collecting, or cataloging, one helpful approach is to separate style from attribution:

- “Castleford-type feldspathic stoneware teapot, ca. 1800–1820” works well when the form and decoration match the

tradition, but the maker can’t be securely pinned down. - “Castleford Pottery (David Dunderdale & Co.), attributed” should be used cautiously and ideally supported by

comparable documented examples or known marks. - When patriotic motifs appear, note that scholarship frequently discusses copying and cross-factory production, so it’s fair to say

“made for the American market” while keeping the maker identification appropriately careful.

Condition and Repairs: What People Check (Because 200-Year-Old Lids Have Lived a Life)

The highest drama areas on a Castleford teapot are exactly where you’d expect: spout, rim, lid seat, hinge/sliding channel, and handle.

Chips at the lid edge or hairline cracks near the spout are common on functional ceramics of this age.

Watch for these common issues

- Restoration around spouts or handles (look for texture changes or overly perfect gloss)

- Repaired cracks along panel edges (old repairs can be stable, but should be disclosed)

- Replaced lids (a lid that “sort of fits” is often the giveaway)

- Metal elements such as pins or staples on some related wareshistorical, but important for condition notes

If you’re buying, prioritize structural integrity over cosmetic perfection. A tiny edge nick on a lid can be “honest age.”

A repaired spout that changes the pour angle can be “honest chaos.”

Care and Use: Display Piece or Working Teapot?

Many collectors treat Georgian-era stoneware as display-firstand honestly, that’s the safest choice. If someone does use

an antique teapot for serving, the main concern is thermal shock: rapid temperature changes can stress old ceramics and

old repairs.

Gentle care guidelines

- Skip the dishwasher. (Your teapot did not survive the 1800s to be power-washed like a casserole dish.)

- Use lukewarm water for rinsing and cleaning; avoid sudden hot-to-cold swings.

- Dry thoroughly, especially around lid mechanisms and metal pins.

- Store the lid safelyseparately if neededto reduce pressure and accidental impacts.

Decorating With a Georgian Castleford Teapot

A Castleford-type teapot is a rare home accessory that can look right in almost any setting:

- On a bookshelf beside history or design books, where the relief panels echo book spines and architecture.

- On a tray with a small stack of cups or a sugar bowlinstant “tea vignette,” no castle required.

- In a modern kitchen as a single sculptural statement piece; the pale stoneware reads clean and intentional.

Pro tip: keep surrounding items simple. The teapot already brought columns, acanthus, and maybe an eagle. Let it have the spotlight.

Common Misconceptions (Let’s Save You a Comment-Section Argument)

- Myth: “Castleford” always means the exact Castleford Pottery.

Reality: “Castleford-type” is widely used for similar wares made elsewhere. - Myth: It’s porcelain because it’s white.

Reality: Many are feldspathic stoneware with a pale body and glossy glaze. - Myth: If it’s unmarked, it’s fake.

Reality: Many authentic period ceramics are unmarked; context and comparison matter. - Myth: A patriotic motif proves it was made by Castleford Pottery.

Reality: Scholarship discusses copying and attributions across makers for American-themed wares.

Real-World Experiences With a Georgian Castleford Teapot ()

Ask ten collectors what it’s like to encounter a Georgian Castleford teapot in the wild, and you’ll get ten variations on the same emotion:

delight followed by immediate overthinking. The first experience is often visualspotting that pale stoneware glow and the

crisp, molded decoration from across a table at an antique fair. People describe a moment of “Wait… is that one of the sliding-lid ones?”

followed by the careful, respectful reach of someone handling history with the concentration of a bomb-defuser… but with better manners.

A common second experience is the lid test. Not a rough tugmore like a gentle conversation: “Hello, are you original?” When the lid

glides smoothly (or the hinge sits properly), it’s oddly satisfying, like a drawer closing with a perfect soft click. When it doesn’t, the teapot

still teaches something: lids and bodies get separated, repaired, and remarried over centuries, and “close enough” was sometimes the household standard.

That’s when collectors start comparing finial shapes, rim profiles, and how the glaze looks in the lid channelbecause apparently the brain loves

a mystery when it comes with pottery.

Museum encounters are a different kind of experience: less treasure-hunt, more “wow, this object has documentation.” Standing near a labeled example

can feel like meeting a celebrity with a résumé. The label might note “Castleford-type,” list a date range, and mention patriotic motifs made for the

American market. For many people, that’s when the teapot stops being just a pretty thing and becomes a story about trade, taste, and identityhow

English factories responded to American demand, and how American households used imported goods to express style and sentiment.

There’s also the practical experience of living with one. Owners often discover that the teapot changes how they style a room: it

naturally pulls in other quiet, classical shapesan old book, a small framed print, a plain linen clothbecause too much visual noise competes with

the relief decoration. Some people place it in a kitchen for everyday enjoyment and find themselves weirdly motivated to keep the counter tidy,

as if the teapot is silently judging modern clutter (fair).

And finally, there’s the experience of conversation. A Castleford teapot is a social objecttea wares always were. Visitors ask about the unusual lid,

the crisp molded panels, or the surprising American eagle. Even people who don’t “do antiques” tend to lean in for a closer look. That’s the charm:

it’s decorative art that invites curiosity, starts stories, and makes the past feel close enough to touchwithout requiring anyone to wear a powdered wig.

Conclusion

A Georgian Castleford teapot sits at the intersection of design, technology, and transatlantic culture: classical ornament rendered through

industrial molds, smart lids built for real tea service, and (in many cases) imagery that connected English production to American identity and demand.

Whether you’re collecting, writing, or just admiring, the best approach is evidence-based and joyful: learn the materials, study the shapes, compare

documented examples, and appreciate that “Castleford” can mean both a specific pottery story and a broader style family.

The reward is a piece that feels surprisingly modern in its claritywhile still carrying that unmistakable Georgian sense of “Yes, I am practical…

but I would also like to be admired.”