Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Are Planetary Boundaries, Exactly?

- Which 6 Planetary Boundaries Have We Already Crossed?

- 1. Climate Change: Turning Up the Global Thermostat

- 2. Biosphere Integrity: The Great Unraveling of Nature

- 3. Land-System Change: Turning Forests into Fields and Cities

- 4. Freshwater Change: Stressing the Planet’s Water Cycle

- 5. Biogeochemical Flows: Overloading the Nitrogen and Phosphorus Cycles

- 6. Novel Entities: Swimming in a Chemical Soup

- And the Others? Ocean Acidification, Aerosols, and Ozone

- Why Breaching Planetary Boundaries Matters for People

- How Did We Push the Planet Beyond Its Safe Operating Space?

- Signs of Hope: We Know What Works

- What It Feels Like to Live on a Planet in Overshoot (Experience-Based Reflections)

- Conclusion: Overshoot Is a Warning, Not a Sentence

Imagine the planet came with an owner’s manual and a big red line that said:

“Do not cross.” Now imagine humanity saw that line, shrugged, and did a running

jump right over it. That, in a nutshell, is what scientists mean when they say

we’ve breached six of the Earth’s nine planetary boundaries – the limits that

keep our world stable, predictable, and friendly to human life.

This isn’t just about polar bears, distant ice sheets, or sad graphs in UN

reports. Crossing planetary boundaries affects everything from the price of

your groceries to the air you breathe and the water that comes out of your

tap. The good news? We still have options. The bad news? We’re very much

in the “don’t hit snooze again” phase of planetary alarms.

What Are Planetary Boundaries, Exactly?

The planetary boundaries framework was introduced in 2009 by a team of

Earth system scientists led by Johan Rockström and colleagues. It identifies

nine critical Earth processes that regulate the planet’s stability – things

like climate, biodiversity, freshwater, and the chemical balance of the

atmosphere and oceans. Each boundary has a “safe operating space” for

humanity. Go beyond it, and the risk of abrupt, large-scale, or irreversible

change shoots up.

Think of it as a dashboard on a spaceship. Green means “we’re good,” yellow

means “maybe slow down,” and red means “you are now experimenting with the

only planet you’ve got.”

The Nine Planetary Boundaries at a Glance

- Climate change

- Biosphere integrity (biodiversity and ecosystem health)

- Land-system change (how we transform forests, grasslands, and soils)

- Freshwater change (blue water in rivers and lakes, and green water in soils)

- Biogeochemical flows (nitrogen and phosphorus cycles)

- Novel entities (chemicals, plastics, and other synthetic substances)

- Stratospheric ozone depletion

- Ocean acidification

- Atmospheric aerosol loading (tiny particles from pollution, dust, smoke)

Crossing one boundary doesn’t mean instant catastrophe, but multiple red

lights at once can interact in nasty ways – for example, climate change

plus biodiversity loss plus pollution can push ecosystems past tipping

points.

Which 6 Planetary Boundaries Have We Already Crossed?

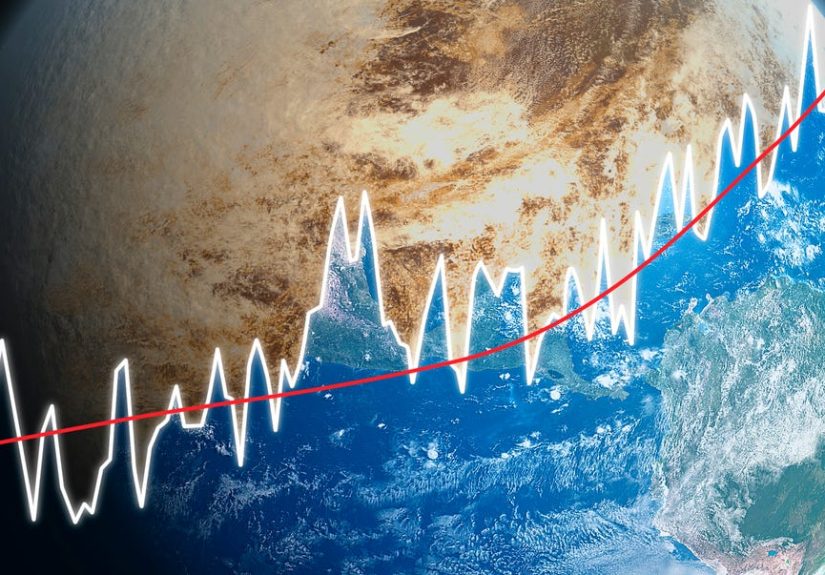

According to a 2023 update of the planetary boundaries framework published in

Science Advances, humanity has already transgressed six of the nine

boundaries: climate change, biosphere integrity, land-system change,

freshwater change, biogeochemical flows, and novel entities.

1. Climate Change: Turning Up the Global Thermostat

The climate boundary is based on greenhouse gas concentrations and global

temperature. We’ve warmed the planet by about 1.2–1.3°C above pre-industrial

levels, mainly by burning fossil fuels and clearing forests. That may sound

small, but it’s already driving more intense heatwaves, extreme rainfall,

wildfires, and rising seas.

The safe zone for climate change is roughly aligned with the Paris Agreement’s

goal of limiting warming to well below 2°C, preferably 1.5°C. Right now,

our emissions pathway is more “roller coaster with no brakes” than “gentle

Sunday drive.”

2. Biosphere Integrity: The Great Unraveling of Nature

Biosphere integrity is a fancy way of asking: how alive and functional is

the living web that supports us? This boundary tracks species extinctions and

the health of ecosystems. We’re losing species much faster than the natural

background rate, and many ecosystems – from coral reefs to tropical forests –

are under severe stress.

When biodiversity collapses, ecosystem services we rely on – like pollination,

fertile soil, clean water, and natural climate regulation – start to crumble.

You can’t run a high-tech global economy on a dying biosphere any more than

you can run a marathon without a working heart.

3. Land-System Change: Turning Forests into Fields and Cities

Land-system change refers to how much natural land we convert to farms,

pastures, and built environments. Clearing forests for agriculture, mining,

and infrastructure fragments habitats, releases stored carbon, and disrupts

local climate and water cycles.

A clear example is the Amazon basin. Deforestation, fires, and land

degradation are threatening to flip parts of the forest from a carbon sink

into a carbon source – a shift that would echo through the global climate

system and regional rainfall patterns.

4. Freshwater Change: Stressing the Planet’s Water Cycle

The freshwater boundary covers both “blue water” (rivers, lakes, groundwater)

and “green water” (soil moisture for plants). We’ve altered the water cycle

through damming rivers, draining wetlands, over-pumping aquifers, and changing

rainfall patterns via climate change.

Result: more frequent droughts in some regions, more devastating floods in

others, and growing competition over water for drinking, farming, hydropower,

and ecosystems. When rivers run dry or flood unpredictably, food security and

livelihoods quickly follow.

5. Biogeochemical Flows: Overloading the Nitrogen and Phosphorus Cycles

Nitrogen and phosphorus are essential nutrients for plant growth – but too

much of a good thing can turn toxic. Industrial fertilizer use, intensive

livestock production, and sewage discharge have overloaded rivers, lakes, and

coastal seas with nutrients.

The result is algal blooms, dead zones with little or no oxygen, fish kills,

and drinking water contamination. If you’ve seen photos of neon-green lakes

or heard about major coastal dead zones, you’ve seen this boundary in action.

6. Novel Entities: Swimming in a Chemical Soup

“Novel entities” includes synthetic chemicals, plastics, pesticides,

industrial compounds, and other substances that didn’t exist in significant

quantities before the industrial era. Scientists now estimate we’ve exceeded

the safe boundary for chemical pollution, as the volume and variety of

these substances outpace our ability to assess and manage their risks.

Microplastics have been found everywhere from the deepest ocean trenches

to human blood and placentas. Persistent pollutants like PFAS (“forever

chemicals”) are turning up in drinking water and wildlife around the world.

This isn’t just untidy – it’s a direct threat to human health and ecosystem

stability.

And the Others? Ocean Acidification, Aerosols, and Ozone

At the time of the 2023 planetary boundaries assessment, ocean acidification

was very close to the threshold, atmospheric aerosol loading was regionally

over the boundary but not yet globally quantified, and the stratospheric

ozone layer was showing signs of recovery thanks to the Montreal Protocol.

More recent analyses, however, suggest that ocean acidification has now

crossed into unsafe territory, effectively turning it into the seventh

breached boundary. The oceans have absorbed a large share of our CO₂

emissions, becoming 30–40% more acidic since pre-industrial times, with

serious consequences for coral reefs, shell-forming organisms, and marine

food chains.

The ozone story offers a rare bright spot: global action to phase out

ozone-depleting chemicals is working, and the ozone layer is slowly healing.

It’s a powerful reminder that coordinated policy can pull a planetary

boundary back from the brink.

Why Breaching Planetary Boundaries Matters for People

Planetary boundaries might sound abstract, but they show up in very concrete

ways in your daily life – sometimes literally in your lungs and on your

dinner plate.

Health Impacts: From Air You Breathe to Food You Eat

Research is increasingly linking breached boundaries with health risks.

Air pollution and aerosols are tied to respiratory and cardiovascular

diseases. Chemical pollution and novel entities contribute to cancers,

endocrine disruption, developmental problems, and mental health stress.

Changes in freshwater availability and quality increase the risks of

waterborne diseases and food insecurity.

Climate change multiplies these dangers: heat waves strain hearts and

kidneys, extreme events displace communities, and disrupted agriculture

can push food prices higher. This is not a distant “environmental” problem

– it’s a public health and economic stability problem.

Economic and Social Risks

Crossing planetary boundaries increases the risk of shocks to food systems,

supply chains, infrastructure, and financial markets. Droughts can ruin

harvests, floods can wipe out homes and factories, and storms can cripple

power grids and ports. As multiple boundaries are breached, such shocks

can overlap, making it harder for communities and economies to recover.

These risks are not evenly shared. Low-income communities and countries

that contributed least to the problem are often the most exposed and the

least able to adapt – a core climate justice and environmental justice issue.

How Did We Push the Planet Beyond Its Safe Operating Space?

The short answer: we built a global economy that assumes infinite extraction

on a finite planet. The long answer involves fossil fuels, land use, and a

lot of linear “take–make–waste” thinking.

The Fossil Fuel Factor

Fossil fuels sit at the center of the planetary boundaries story. Burning

coal, oil, and gas drives climate change, acidifies the ocean, and releases

aerosols and pollutants that harm human health. Fossil fuel-based plastics

and chemicals help push the novel entities boundary beyond safe limits.

In other words: our energy system hasn’t just warmed the planet; it has

quietly rewritten multiple Earth systems at once.

The Land and Food System Piece

Agriculture and land use are another major driver. We clear forests to grow

crops and raise livestock, use large amounts of fertilizer to boost yields,

and often waste a significant share of the food produced. That combination

pushes us over boundaries for land-system change, biogeochemical flows,

biodiversity, and freshwater.

Meanwhile, plastic and chemical pollution is embedded in the modern food

system – from packaging microplastics to pesticide residues. Recent studies

show, for example, how plastic contamination is now widespread even in

remote river systems like the Amazon, highlighting how deeply these novel

entities have infiltrated the global environment.

Signs of Hope: We Know What Works

If all of this sounds grim, it is. But it’s not hopeless. The planetary

boundaries framework isn’t a doomsday clock; it’s a risk dashboard designed

to guide better choices.

We’ve Fixed Global Problems Before

The recovery of the ozone layer is proof that international agreements can

work. When scientists showed that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were shredding

the ozone layer, countries came together to phase them out. The planetary

boundary for ozone is now moving back toward the safe zone.

That same logic – act early, act together, and align policy with science –

can be applied to climate change, chemical pollution, and other boundaries.

Pathways Back Toward the Safe Zone

- Rapidly phase out fossil fuels and scale up renewable energy, energy efficiency, and electrified transport.

- Protect and restore ecosystems such as forests, wetlands, coral reefs, and mangroves to rebuild biosphere integrity and store carbon.

- Transform food systems by cutting food waste, changing diets, improving soil health, and reducing fertilizer and pesticide overuse.

- Shift to a circular economy that designs out waste, reuses materials, and reduces the flow of plastics and toxic chemicals.

- Strengthen environmental health protections so communities are shielded from pollution, contaminated water, and extreme heat.

None of this is simple, but most of it is technically and economically

feasible. The limiting factor is less about technology and more about

politics, incentives, and our willingness to treat planetary health as the

foundation of every other priority.

What It Feels Like to Live on a Planet in Overshoot (Experience-Based Reflections)

Living in an era where six planetary boundaries have already been breached

doesn’t feel like a single, dramatic moment. It feels like a series of

subtle shifts that gradually become impossible to ignore.

It’s the farmer who notices that the rainy season no longer shows up “on

time.” Instead of reliable patterns, rainfall arrives in violent bursts

that flood fields one month and disappear for months afterward. At first,

it seems like bad luck. After several years in a row, it becomes a

question of survival – which crops to plant, whether to take out loans,

whether younger family members should stay or leave for the city.

It’s the coastal community that used to see extreme floods once in a

generation but now gets “once-in-a-century” storms every five or ten

years. The first flood causes shock and a scramble to rebuild. The second

leaves people exhausted and emotionally drained. By the third, residents

are arguing at town meetings about buyouts, seawalls, and whether it makes

sense to keep rebuilding in the same spot.

Overshoot shows up in city life too. Heat waves that used to be unpleasant

are now life-threatening, especially for older adults, people with chronic

illness, and workers with outdoor jobs. Air quality warnings become part

of the normal weather report. Parents pay closer attention to what’s in

their children’s food, water, and toys, because microplastics and “forever

chemicals” have turned product labels into mini chemistry lessons.

For health professionals, the planetary boundaries story is no longer just

a theoretical chart in a journal article – it’s the backdrop to rising

cases of heat stress, asthma, vector-borne diseases, and anxiety related

to climate and ecological disruption. Hospitals prepare for more frequent

extreme-weather emergencies. Public health officials start talking about

“planetary health” – the recognition that human well-being depends on the

health of Earth systems – in the same breath as vaccines and nutrition.

At the same time, overshoot is inspiring new forms of community and

creativity. Neighborhood groups organize tree-planting campaigns and

cooling centers during heat waves. Farmers experiment with regenerative

practices that rebuild soil, reduce fertilizer dependence, and make their

land more resilient to drought. Local governments test out nature-based

solutions like wetland restoration to handle floods more gracefully.

Many young people already understand the planetary boundaries story at a

gut level. They grew up with news of coral bleaching, wildfires, and

plastic-choked oceans. For them, studying climate science or environmental

policy isn’t just an academic interest; it’s a way to gain tools for

navigating the century they’ll spend on this planet. Many feel grief and

anger – but also a stubborn sense of determination to do better than the

generations that brought us here.

Perhaps the most powerful experience of living in planetary overshoot is

the shift in perspective. Once you see the boundaries, you can’t un-see

them. Everyday decisions – from food choices to how you travel, where you

bank, and which policies you support – take on a different weight. The

goal isn’t perfection; it’s alignment, asking: “Is this choice moving us

closer to or further from the safe operating space for humanity?”

That mindset shift is uncomfortable, but it’s also liberating. The same

actions that help bring us back within planetary boundaries – cleaner

air, healthier food systems, more green spaces, less toxic pollution –

tend to make day-to-day life better right now, not just for some future

generation. You don’t have to wait for a global treaty to feel the

difference when your city plants more trees, when your power grid gets

cleaner, or when your river is swimmable again.

Living in a time when six planetary boundaries have been breached means we

are the generation that doesn’t get to pretend the planet is infinite. But

it also means we are uniquely placed to help steer Earth back toward a

safer, more stable state. That’s a heavy responsibility – and a remarkable

opportunity.

Conclusion: Overshoot Is a Warning, Not a Sentence

Humanity has pushed six of Earth’s nine planetary boundaries beyond their

safe limits, and evidence suggests ocean acidification is now joining the

list. That doesn’t mean the story is over; it means the stakes are finally

clear. The same ingenuity that built an industrial civilization big enough

to nudge planetary systems can be used to redesign how we power our lives,

grow our food, and handle materials so that we live within the planet’s

limits instead of against them.

The planetary boundaries concept can feel intimidating, but it’s ultimately

a tool for hope: a map of the safe operating space where people and nature

can thrive together. The sooner we act to pull those red dials back toward

green, the more choices and resilience we preserve for ourselves and for

future generations.

SEO Summary

meta_title: Humanity Has Overstepped 6 Planetary Boundaries

meta_description:

Scientists warn we’ve crossed 6 of Earth’s 9 planetary boundaries. Here’s

what that means, why it matters, and how we can pull back from the brink.

sapo:

Scientists now say humanity has pushed six of Earth’s nine planetary

boundaries beyond their safe limits, from climate change and biodiversity

loss to freshwater stress, fertilizer overload, and chemical pollution. In

this in-depth guide, we break down what planetary boundaries are, which

ones we’ve crossed, how that overshoot shows up in everyday life, and what

it will take to move back into a safer operating space for people and the

planet. Along the way, you’ll see why this is more than an environmental

headline – it’s a roadmap for protecting health, food, and stability in

the decades ahead.

keywords:

planetary boundaries, safe operating space for humanity, climate change and

biodiversity loss, freshwater and nitrogen pollution, novel entities and

chemical pollution, Earth system limits, planetary health