Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Vintage Human Portraits Make Animal Characters Instantly Iconic

- Meet the Spark: The Bored Panda Project

- The Visual DNA: What Makes a Portrait Look “19th Century”

- Anthropomorphic Art: Why It Works (and Why It’s Funny)

- How to Create Your Own Vintage-Style Animal Portraits

- Historical Touchstones to Elevate Your Set

- Storytelling: Sequencing 26 Characters Like a Real Family Album

- Practical Workflow: From Sketch to “Antique” Print

- Common Mistakes (And How to Avoid Them)

- Inspiration Vault: Look to Museums & Archives

- Case Study: Designing Three Signature Animals

- SEO-Friendly FAQ (Without the Fluff)

- Conclusion: A Menagerie With Old-Soul Charm

- 500-Word Experience Add-On: What I Learned Creating a 26-Image “Animal Family Album”

What happens when you mix a stately Victorian studio, a dash of sepia-toned mystery, and a wardrobe full of waistcoatsbut the models are animals? You get a whimsical gallery where foxes smolder like 19th-century aristocrats and owls look like they just defended a dissertation in tweed. Inspired by a viral Bored Panda post titled “I Illustrated Animals In The Style Of Vintage Human Portraits (26 Pics),” this article unpacks the look, the methods, and the history behind these delightfully anthropomorphic portraitsand shows you how to create the vibe in your own illustrations or photo edits without time-traveling to 1844.

Why Vintage Human Portraits Make Animal Characters Instantly Iconic

Vintage human portraiture is shorthand for gravitas. A single oval vignette, a stiff pose, and a moody backdrop can make almost anything feel importantyes, even a raccoon with impeccable sideburns. Classic studio conventions (head-and-shoulders framing, soft front lighting, neutral backdrops) were designed to highlight status, personality, and “a truthful likeness.” When you place animals inside that visual grammar, the result reads as witty and strangely believable: our brains automatically search for human stories inside those formal cues. Early portrait methods like the daguerreotype were literally marketed on their fidelity to realityno wonder the style still carries authority today.

Meet the Spark: The Bored Panda Project

The Bored Panda feature that inspired this deep dive credited illustrator Mike Koubou (a community member) and introduced the set with a playful premise: an “old family album” discovered in the atticexcept the “relatives” are rendered as elegantly dressed animals. It’s a clever narrative wrapper that makes the series feel found rather than made, nudging viewers to suspend disbelief and lean into the nostalgia. Published in late 2023, the project resonated because it merged internet meme logic (animals! costumes!) with bona fide historical visual language.

The Visual DNA: What Makes a Portrait Look “19th Century”

Before you paint a stoat in a silk cravat, decode the building blocks of 1800s portrait aesthetics. Three ingredients matter most: format, finish, and pose.

1) Format: From Daguerreotype to Cabinet Card

Daguerreotypes (from 1839) are mirror-polished images on silver-coated copperrazor sharp, often cased, and exquisitely formal. They launched the portrait boom worldwide and anchored the serious, front-facing stance that still reads as “official.” If you want intellectual gravitas for your animal sitter, emulate this clarity, the head-and-shoulders crop, and that sober, studio-bench posture.

By the 1860s and beyond, cartes-de-visite and cabinet cards made portrait collecting mainstream: small albumen prints mounted to card stock, traded with friends or slotted into family albums. Their paper textures, deckled edges, and printed studio imprints are visual cues you can mimic in your frames or borders.

2) Finish: Tintype Mood & Sepia Memory

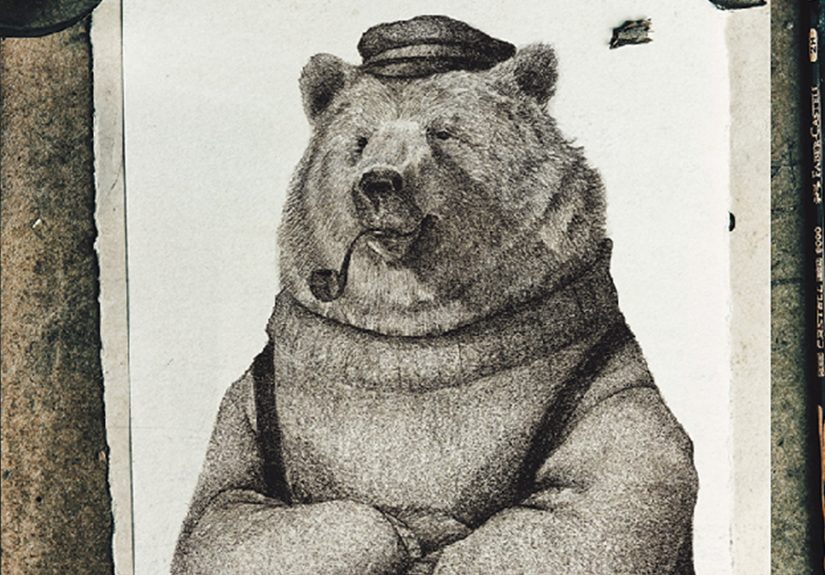

Tintypes (popular from the late 1850s) introduced durable, inexpensive portraits on lacquered iron. They often present deep contrast, a slightly metallic sheen, and fine surface wearperfect for an adventurous fox or a dapper bear with a scuffed past. Museum and archive collections show how tintype tones range from silvery neutrals to warm browns; recreating that tonality sells the “found in a trunk” illusion.

3) Pose & Props: Stillness, Symmetry, and Signifiers

Victorian studio portraits favored calm poses, straight-on or three-quarter views, and restrained gestures (chin slightly lifted, hands folded or resting on a pedestal). Minimal propsbooks, chairs, pocket watchessignaled status. Transpose those cues to animals, and each accessory becomes character design: a monocle implies learned wisdom; a glove tucked into a belt suggests travel or trade; a cameo brooch on a stoat? Pure aristocracy. Archival sets are full of occupational and social portraits that show how a single prop changes the story.

Anthropomorphic Art: Why It Works (and Why It’s Funny)

We’re wired to read faces and infer stories. Give a fox human posture and a waistcoat, and your brain bridges the gap“Oh, he’s the brooding cousin who only drinks Darjeeling.” This is classic anthropomorphism, which stretches back across art history, satire, and children’s literature. The magic lies in friction: animal features (muzzle, feathers, whiskers) clash with courtly dress and etiquette, producing a comic seriousness. The more convincingly you borrow 19th-century portrait codes, the more the joke landsand the more endearing it becomes.

How to Create Your Own Vintage-Style Animal Portraits

Whether you illustrate digitally, paint in oils, or composite photos, this workflow recreates the vibe without the mothballs.

Step 1: Cast Your “Sitters”

- Pick animals for personality resonance. Owls read as scholars, foxes as wily nobles, bulldogs as stoic generals, cats as geometers of disdain. Let the animal’s natural silhouette determine collar height and hat shape (e.g., long-necked birds wear high collars beautifully).

- Match animal textures to fabrics. Dense fur contrasts well with crisp linen; sleek feathers pop against velvet capes; scales look regal next to satin lapels.

Step 2: Research Authentic Studio Cues

- Framing & Crop: Classic head-and-torso; keep the crown of the head near the top third of the frame. Consider an oval vignette or a narrow matte to echo album pages.

- Background: Neutral, painted muslin or a softly graduated tone. For extra authenticity, emulate mottled backdrops from cabinet-card studios.

- Lighting: Simulate north-facing window light: soft, directional, and slightly above eye level. Add a gentle fill to keep shadows readable.

Step 3: Color, Tonality, and Surface

- Limit the palette. Warm browns, olive blacks, and ivory whites sell the 19th-century mood. Introduce subtle hand-coloring on cheeks, eyes, or jewelry.

- Age the surface. Add faint scratches, silvering at the shadows, corner wear, and matte paper grain. Save “big” damage (cracks, tears) for only a few images so the set feels plausibly preserved.

Step 4: Wardrobe & Props

- Costume builds character. A velvet waistcoat and watch chain says “financier.” A cape and cane whispers “midnight walker.” Keep patterns subtle; 19th-century portrait lenses and emulsions often subdued extreme contrast in fabrics.

- Frame it like an heirloom. Add period-appropriate card mounts or oval passe-partout with a studio imprint (invent a fictional studio and city for flavor).

Step 5: Expressions & Anatomy

- Find the human in the animal. Slight eyebrow angles (even on feathered brows), eyelid droop, and micro-asymmetry make faces feel “lived in.”

- Respect anatomy. Collars should sit where necks would be; whiskers shouldn’t collide with lapels; beaks need cutaways in shirt fronts. The more anatomically possible the costume, the more convincing the portrait.

Historical Touchstones to Elevate Your Set

Want your owl professor to pass muster with curators? A few historical nods go a long way.

- 1839The Year It All Began. Referencing the daguerreotype’s 1839 public debut ties your series to photography’s origin myth. A title like “Professor Strix, c. 1840” instantly telegraphs context.

- Cabinet-Card Era Details. Add printed studio marks, embossed borders, and album page shadows to fake the vernacular of family albums that flourished in the late 19th century.

- America’s Portrait Studios. Name-drop Brady-style studios or early adopters in New York and Philadelphia in metadata or captions; even a wink like “From the Menagerie & Brady Co., Broadway” rewards history nerds.

- Earliest Selfie Easter Egg. Slip a tiny cameo on a wall that reads “Cornelius, 1839” to honor Robert Cornelius’ famed early self-portraitthe proto-selfie that launched a million mirrors.

- Tintype Texture. For your more rough-and-tumble animals (looking at you, raccoon), emulate tintype micro-abrasions and contrast to suggest itinerant fairground studios.

Storytelling: Sequencing 26 Characters Like a Real Family Album

The Bored Panda piece framed the set as an attic discovery, so sequence your 26 images as if they span decades: earlier “relatives” in daguerreotype style, younger ones in cabinet-card style, and a rebellious cousin in tintype. Thread tiny motifs (a signet ring, a cane, a brooch) across generations to imply inheritance. End with a group montagea faux studio “family reunion”to tie the narrative bow.

Practical Workflow: From Sketch to “Antique” Print

- Thumbnail & silhouette pass (30–60 minutes): Focus on the animal’s head/neck and how clothing supports the shape.

- Costume research (1–2 hours): Pull references from museum archives (lapel shapes, collars, hat crowns). Keep embellishments era-consistent.

- Clean line art or underpainting (1–2 hours): Lock the gaze, then build features around that anchor.

- Lighting & material study (2–3 hours): Render fur/feather direction under a single key light; fabrics should reflect softly.

- Aging & finishing (30–90 minutes): Add matte paper grain, light vignettes, edge wear, and a studio imprint.

Common Mistakes (And How to Avoid Them)

- Modern contrast curves: Over-crunchy blacks kill the 19th-century feel. Keep midtones rich and blacks slightly lifted.

- Busy patterns: Loud stripes and neon dyes scream 21st century. Prefer muted wools, twills, and velvets.

- Floating collars: Collars must hug the animal’s believable neck volume.

- Sticker-book aging: Don’t plaster every image with deep cracks. Use subtle, varied wear so the set feels authentic.

Inspiration Vault: Look to Museums & Archives

For reference gold, browse digitized collectionsdaguerreotypes by Brady’s studio, occupational portraits, and troves of tintypes. Studying real mounts, handwriting, and studio backdrops will drastically improve your fakes because you’ll start noticing tiny cues (embossed ovals, blind-stamped borders, corner rounding) that most viewers can’t name but instantly recognize. Recent exhibitions at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery and holdings across the Library of Congress make this research accessible and richly visual.

Case Study: Designing Three Signature Animals

The Owl Professor (Ambrotype Aura)

Give your owl a narrow collar with a high stand, a small bow tie, and a robe lined with satin. Light from 45° left, softly fill the right side, and end with a gentle oval vignette. A cameo with tiny Greek letters signals scholarship without text.

The Fox Industrialist (Cabinet-Card Confidence)

A brushed velvet waistcoat, watch chain, and tidy pocket square do wonders for vulpine charisma. Keep the background a warm, mottled brown and add a studio imprint (“Sable & Sons, Fifth Avenue”). Slight three-quarter turn makes him feel on the move.

The Raccoon Adventurer (Tintype Grit)

Dress him in a dark frock coat with soft wear at the elbows. Push contrast a notch higher, add faint surface scratches, and keep the pose square to cameraso when he stares down the lens, it’s delightfully confrontational.

SEO-Friendly FAQ (Without the Fluff)

What is a daguerreotype?

An early photographic process introduced publicly in 1839, producing sharp images on a silver-coated copper plate. Think: ultra-formal, ultra-detailed portraits.

What are cabinet cards and cartes-de-visite?

They’re albumen prints mounted on card stock, popular in the late 19th century for studio portraits and family albumsbasically the Instagram prints of their day.

What defines a tintype look?

Higher contrast, iron support, and durable surfaces that pick up characteristic scuffsperfect for rugged, story-heavy characters.

Conclusion: A Menagerie With Old-Soul Charm

Vintage human portrait style gives animal characters a backstory at a glance. By borrowing tried-and-true conventionsformal pose, restrained light, historical finishesyou can make a fox feel like an heir to a shipping empire and an owl feel like he grades papers by candlelight. That’s why the “I Illustrated Animals…” series hits so hard: it pairs internet-native whimsy with museum-grade visual language in a way that feels both fresh and timeless.

sapo: What do you get when you dress animals in Victorian finery and shoot them like 19th-century studio portraits? A witty, believable “family album” that blends daguerreotype dignity with internet whimsy. We break down the history (daguerreotypes, cabinet cards, tintypes), the visual cues (lighting, props, textures), and a practical workflow to create your own museum-grade anthropomorphic portraitsjust like the viral “I Illustrated Animals in the Style of Vintage Human Portraits (26 Pics)” project. Expect character design tips, aging tricks, and three mini case studies (owl, fox, raccoon) you can apply today.

500-Word Experience Add-On: What I Learned Creating a 26-Image “Animal Family Album”

When I set out to build my own 26-image set, I treated it like curating a believable family archivejust with more feathers. The first breakthrough came when I stopped thinking “costume on animal” and started thinking “wardrobe around anatomy.” For example, collars on owls needed higher stands and curved cutaways to accommodate feathers; fox muzzles required shirtfront scoops so the snout didn’t collide with fabric. It sounds obvious, but designing clothing around the animalrather than slapping a suit on topchanged the whole believability index.

Lighting was next. I built a simple digital “north-light” rig: a broad, soft key, just above eye level, with minimal fill and a barely-there kicker to separate ear tufts. When I cheated the light modern-high-contrast, the portraits felt like cinema stills; when I kept it soft and patient, they felt like heirlooms. Adding a subtle oval vignette and lifting the blacks (instead of crushing them) delivered that “printed on fiber paper” hush.

Surface was the unsung hero. I made three finish presets“Plate” (daguerreotype-sharp, slight mirror bloom in the shadows), “Albumen” (cream whites, low micro-contrast, soft paper grain), and “Tin” (fine scratches, mild edge fall-off). I rotated these across the series and resisted the urge to over-age. That restraint mattered; too many cracks or coffee stains and the illusion becomes Halloween décor. The best “age” is the kind you only notice when you lean in.

Character arcs kept the set from feeling like a costume parade. I wrote one-line bios for each sitter: “Aunt Thalia (barn owl), professor of rhetoric,” “Cousin Rowley (raccoon), prospector turned philanthropist,” “Grandfather Silas (fox), shipping magnate with a fondness for lemon tea.” Those tags drove wardrobe choices (cameos, watch chains) and micro-expressions (a slight beak tilt, a raised whisker). I also reused props across “generations”a ring, a caneto hint at inheritance and family lore.

Color grading took the longest to get right. I built a three-stop curve to mellow highlights and warm midtones, then introduced a whisper of hand-coloringjust enough rose in cheeks or a breath of blue in a ribbon. I tried bolder colorizations, but they broke the spell; historically inspired portraits reward understatement.

Finally, sequencing. I opened with three “founding ancestors” in plate-sharp finishes, then transitioned into albumen-style cabinet cards with embossed mounts, and sprinkled in a handful of gritty tintypes for the roguish branch of the family tree. I ended on a composite “reunion” print, de-sharpened slightly to match early enlargements. The set felt cohesive because each image wasn’t just an isolated gag; it was a chapter in a family saga the viewer could infer.

The big lesson: when you respect the craft of 19th-century portraiturethe light, the paper, the poseyou don’t need to shout the joke. A quiet fox in a waistcoat, perfectly lit and plausibly printed, will do all the talking. And that’s the sweet spot where whimsy meets museum-grade credibility.