Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Is Corviale (and Why Does It Look Like a Concrete Snake)?

- The ’80s Dream: A Giant Building With Small, Human Goals

- From Dream to “Uh-Oh”: Why Corviale Struggled

- What’s Changing: Regeneration Instead of Demolition

- How to Photograph Corviale Without Turning People Into “Aesthetic Proof”

- 18 Pics: Photo Prompts That Tell the Truth Without Exploiting Anyone

- What Corviale Teaches (Rome-Specific Story, Global Lessons)

- Visiting Corviale: How to Be a Good Guest

- Extended Experience Notes (About ): A Long Walk Along the Serpentone

- Conclusion: Corviale Is Not a MemeIt’s a Neighborhood

Some buildings don’t just sit in a citythey argue with it. Corviale, a massive social-housing complex on Rome’s southwest edge,

is one of those places: part utopian blueprint, part cautionary tale, part living neighborhood that refuses to be reduced to a headline.

From a distance, it looks like a concrete cruise ship that forgot to leave port. Up close, it’s more complicatedbecause people live here,

raise kids here, invent small joys here, and do the daily work of making a “project” into a home.

This story is a deep dive into what Corviale is, why it struggled, what’s changing, and how to photograph it respectfullyespecially when your lens

meets the energy of youth. And because the internet loves a numbered list almost as much as it loves judging architecture, I’ve included

“18 Pics” worth of photo prompts you can use without turning real lives into props.

What Is Corviale (and Why Does It Look Like a Concrete Snake)?

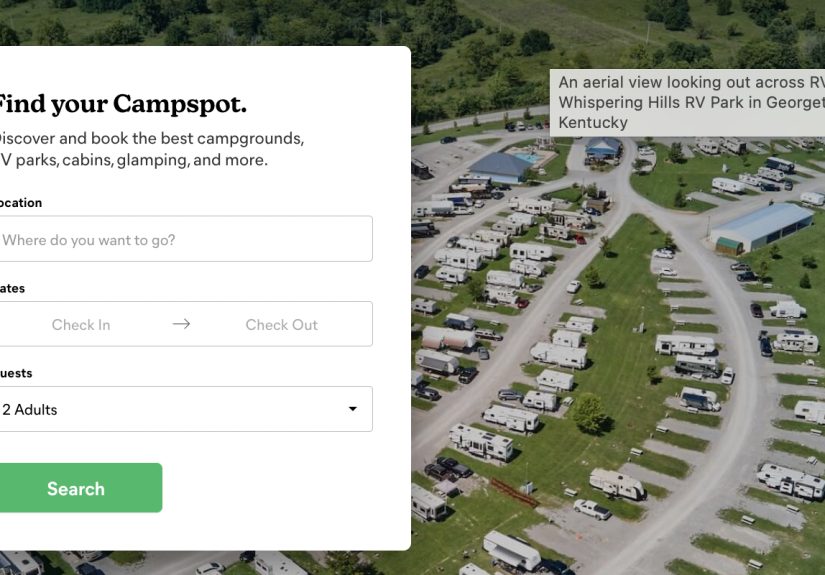

Corvialeoften nicknamed il Serpentone (“the big snake”)is a megastructure built as public housing on Rome’s periphery.

It’s famous for one simple reason: scale. The main slab stretches for nearly a kilometer, making it feel less like an apartment building and more like

an urban border you can’t ignore.

The plan came out of a period when many cities were trying to solve housing shortages with big, centralized solutions:

build fast, build dense, and add services so residents don’t have to travel far for daily needs.

In theory, Corviale was designed as a “city within a city,” with housing plus shops, community spaces, and public services integrated into the complex.

The ’80s Dream: A Giant Building With Small, Human Goals

Megastructure logic: one roof, many needs

Corviale was conceived in the 1970s and built across the following years, led by architect Mario Fiorentino and a large team.

The big idea wasn’t only “stack apartments.” It was to create an environment where corridors could behave like streets,

shared areas could behave like squares, and built-in services could reduce isolation.

If you’ve ever heard someone say, “Architecture can change lives,” Corviale is the type of project they mean.

The design aimed to combine density with light and ventilation, and to structure movement through entrances, stair cores, and internal circulation.

On paper, it’s not just boldit’s almost tender in its ambition.

The missing ingredient: finishing the neighborhood, not just the building

Here’s the twist: Corviale’s story isn’t simply “Brutalism bad” or “big building scary.”

A lot of the trouble came from what didn’t get completed or didn’t get maintained.

When the “services layer” of a housing plan is delayed or canceled, residents still have needsso informal solutions take over.

That’s not a moral failure; it’s physics. Nature abhors a vacuum. Communities do, too.

From Dream to “Uh-Oh”: Why Corviale Struggled

1) Unfinished services and the famous “problem floor”

One of Corviale’s most discussed setbacks is how a portion meant for commercial and communal functions never worked as intended.

Over time, informal occupations and improvised living arrangements filled spaces that were supposed to serve the broader neighborhood.

The result wasn’t just a planning hiccupit shaped how the building was managed, how it was perceived, and how residents experienced daily life.

2) Maintenance, management, and the slow leak of “broken windows” reality

Big buildings demand big upkeep. When maintenance budgets don’t match the building’s complexity, problems multiply:

elevators break, common spaces degrade, lighting becomes inconsistent, and the “public realm” inside the structure feels less public and more neglected.

That’s not unique to Rome. Housing researchers repeatedly find that distressed large-scale public housing becomes hardest to stabilize

when disinvestment and weak management pile onto concentrated disadvantage.

3) Isolation and stigma: the invisible architecture

Physical distance from opportunity can matter as much as physical distance from downtown.

When jobs, quality schools, healthcare, and reliable transit aren’t easy to reach, a neighborhood can feel like it’s living on a different timetable than the city.

Add stigmamedia narratives, political neglect, outsiders treating the area like a “no-go zone”and you get a social wall built right on top of the concrete one.

4) A familiar pattern: concentrated poverty isn’t just about income

American urban policy debates have been wrestling with similar dynamics for decades:

high-poverty neighborhoods tend to face layered challengesfewer services, higher stress, lower perceived safety, and fewer “bridges” to opportunity.

This is why many U.S. redevelopment strategies put such emphasis not only on buildings, but also on supportive services, safety, schools, and connection to jobs.

What’s Changing: Regeneration Instead of Demolition

Corviale’s reputation often swings between “demolish it” and “preserve it,” but the more interesting reality is in the middle:

renovation, reprogramming of spaces, and neighborhood-led efforts to make the complex healthier and more functional.

Regeneration projects have focused on upgrading common areas, improving public spaces, and addressing long-standing space-use conflicts.

The most hopeful versions of “fixing Corviale” aren’t about pretending the past didn’t happen.

They’re about doing the unglamorous work that makes housing succeed: governance, maintenance, services, and resident participation.

In other words: less sci-fi utopia, more competent city management (the real futuristic technology).

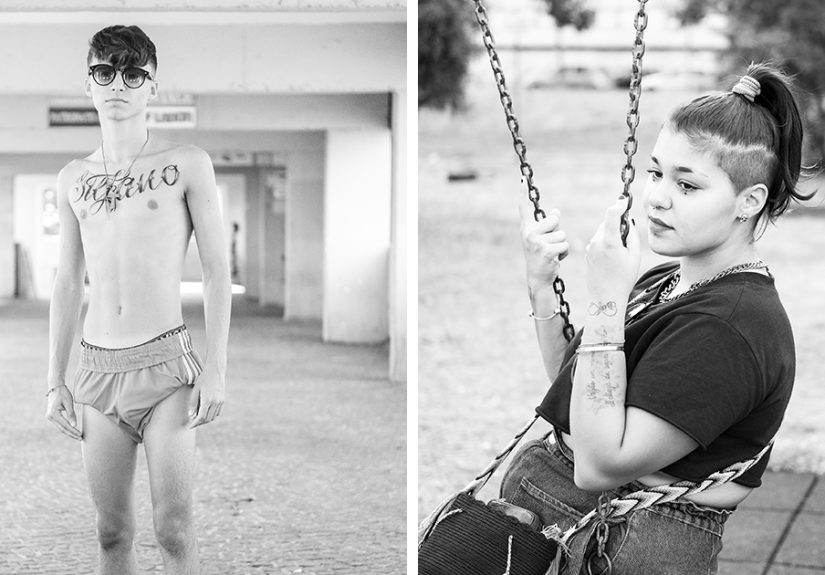

How to Photograph Corviale Without Turning People Into “Aesthetic Proof”

Corviale is visually dramatic, so it attracts photographers. That’s finephotography can document, challenge stereotypes, and reveal everyday dignity.

But there’s a bright ethical line between “telling a story” and “collecting misery for likes.”

Practical respect rules (especially around youth)

- Get consent for identifiable portraits and be extra cautious with minors. If you can’t confirm age and permission, don’t shoot faces.

- Photograph context, not vulnerability: architecture, hands, silhouettes, movement, and community spaces can say a lot without exposing anyone.

- Don’t narrate strangers’ lives from a single frame. Avoid captions that claim crime, addiction, or despair unless you’re reporting with evidence.

- Share the frame: include residents’ art, events, and community initiativesnot only decay.

18 Pics: Photo Prompts That Tell the Truth Without Exploiting Anyone

- The One-Kilometer Line: a wide shot that shows the building’s length against the sky.

- Serpentone Texture Study: close-ups of concrete, railings, repeating windowspatterns that feel almost musical.

- Human Scale vs. Giant Scale: a tiny figure (unidentifiable) crossing an open area in front of the slab.

- Entrances as “City Gates”: photograph one main entry as if it were a subway station or stadium portal.

- Corridor as Street: a vanishing-point hallway shot that makes the building feel like an interior city.

- Vertical Lifelines: elevators/stair coreswhere movement and chance encounters happen.

- Light & Ventilation: frames that highlight how air and light were meant to circulate.

- Layers of Use: a composition showing housing above and community functions below (without identifying people).

- Signs of Care: plants on balconies, DIY repairs, painted doorssmall acts that say “we live here.”

- Community Noticeboard: flyers, announcements, local eventsevidence of neighborhood life.

- Street Art as Memory: murals and tags as informal storytelling.

- Play Without Faces: a basketball hoop, a worn soccer ball, chalk marksyouth presence without portraits.

- Ritual Spaces: a local cultural center, a small chapel, or gathering spot (ask permission where needed).

- Transit Reality: a bus stop or walkway that communicates distance and connection.

- The Long Walk: a series of frames moving along the facadelike a visual “timeline.”

- Inside/Outside Contrast: one frame from within looking out, showing Rome’s periphery beyond the windows.

- Regeneration in Progress: scaffolding, new signage, repairsproof the story isn’t frozen in 1984.

- The Quiet Moment: an early-morning shot when the building feels like a sleeping ship.

What Corviale Teaches (Rome-Specific Story, Global Lessons)

Lesson 1: Housing is a system, not a structure

Corviale shows what happens when a housing plan is treated like a construction project instead of an ongoing civic commitment.

Apartments alone don’t create stability. The “software” matters: maintenance, resident services, governance, safety, schools, and economic access.

Lesson 2: Big scale magnifies both success and failure

When a small building is mismanaged, the damage is contained. When a megastructure is mismanaged, the consequences become a neighborhood-wide reality.

That’s why many U.S. programs aimed at distressed public housing paired physical redevelopment with supportive services and broader neighborhood revitalization:

the goal was not only nicer buildings, but better life chances.

Lesson 3: Stigma is an urban policy problem

Places with reputations for failure struggle to attract resources and opportunities, which can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Corviale’s image as an “urban nightmare” may be dramatic copy, but it can also flatten real lives into a single story.

A more accurate lens is: a neighborhood with serious challenges and serious resilience.

Visiting Corviale: How to Be a Good Guest

- Go with purpose: architecture interest, urban history, community artsnot “I want to see the scary building.”

- Be discreet with gear: don’t treat the place like a film set; ask before lingering in semi-private areas.

- Support local initiatives: if there’s a cultural event or community space open to visitors, show up respectfully.

- Remember it’s home: your photo walk is someone else’s Tuesday.

Extended Experience Notes (About ): A Long Walk Along the Serpentone

If you visit Corviale, the first thing you notice isn’t “danger” or “decay.” It’s distancenot only from central Rome, but from the city’s postcard rhythm.

The bus ride feels like a slow unspooling of scenery: ancient stones give way to newer blocks, then wider roads, then the kind of edges every big city has,

where the map looks emptier than the lives actually living there. And then, suddenly, the Serpentone appearsso long it messes with your sense of proportion.

Your brain wants to file it under “factory” or “warehouse,” because that’s how we’re trained to read scale. But it’s housing. It’s balconies. It’s curtains.

It’s a building that keeps reminding you: people fit inside visions, even when visions don’t fit reality.

Walking along the facade can feel like reading a sentence that refuses to end. Repetition becomes its own language: window, slab, balcony, railingagain and again,

with small variations that start to feel like personality. A bright curtain here. A plant there. A repaired patch that signals someone got tired of waiting for the system

and handled it themselves. The most honest moments are often the quiet oneswhen you’re not searching for “the shot” and you start seeing the ordinary:

a doorway that’s been repainted, a cluster of mailboxes, a hand-scrawled notice that says something is happening tonight.

If you’re photographing, you’ll probably feel the tug-of-war every documentary shooter knows: the architecture is spectacular, but the ethics are real.

The building’s drama invites you to oversimplify, and Corviale punishes that impulse immediately. You’ll see signs of hardship, surebecause hardship exists.

But you’ll also see signs of community in plain view: a cultural space hosting an event, a public area that’s clearly been claimed for gathering, the kind of

informal “we take care of this” maintenance you don’t get from a top-down plan. It’s not romantic; it’s practical.

The presence of young people is often felt more than captured. You might hear a quick burst of laughter down a corridor, the echo of a ball bouncing,

or music leaking from somewhere you can’t quite locate because the building folds sound in strange ways. If you’re doing portraits, consent changes everything:

the moment someone agrees to be photographed, the frame becomes a collaboration, not a theft. Without that, the better choice is to photograph traces

a court, a mural, a path worn into the daily routeimages that acknowledge youth without putting any one young person on display.

By the time you leave, Corviale may feel less like a “failed project” and more like a hard question the city keeps asking itself:

What do we owe people after the ribbon cutting? The building is enormous, yes. But the real weight is the reminder that housing success is built slowly,

in maintenance schedules, social services, transit links, and the everyday dignity of being seen as more than a symbol.

Conclusion: Corviale Is Not a MemeIt’s a Neighborhood

Corviale deserves better than a single adjective. It’s been criticized, mythologized, and used as a shorthand for everything that can go wrong in large-scale housing.

But it’s also a place where people have adapted, organized, and lived real lives inside an unfinished promise.

If you visitor if you simply study ittake the building seriously, but take the residents even more seriously.

The Serpentone may be made of concrete, but the story is made of humans.