Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- First things first: what counts as an ovarian cyst?

- What is ovarian cancer (and why does it get lumped into “cyst talk”)?

- So… do ovarian cysts cause ovarian cancer?

- Simple vs. complex cysts: the ultrasound clues that matter

- Symptoms: why cysts and ovarian cancer can feel confusingly similar

- How doctors evaluate the “cyst vs. cancer” question

- When an ovarian cyst is an emergency (yes, sometimes it is)

- Higher-risk situations: what “more cautious” looks like

- Risk factors and protective factors: where cysts fit in (and where they don’t)

- Practical FAQs (because your brain is already asking)

- Conclusion: the link in one sentence (okay, two)

- Experiences people share (and what they often learn along the way)

- 1) “I had a cyst and it disappearedso why was I so scared?”

- 2) “My cyst was painful, but it still wasn’t cancer.”

- 3) “Endometriosis made everything feel murky.”

- 4) “After menopause, the conversation sounded differentand that was okay.”

- 5) “Persistent symptoms were the real signal, not a single test.”

If you’ve ever had a pelvic ultrasound, you might have heard the phrase “ovarian cyst” and immediately thought,

“Is this… the big scary thing?” Totally normal reaction. “Cyst” sounds like something that should come with

a warning label and dramatic background music.

Here’s the good news: most ovarian cysts are common, harmless, and go away on their own. The more nuanced news:

sometimes an ovarian mass that looks “cyst-like” can be something that needs closer attentionespecially

after menopause or when certain high-risk features show up. The goal of this article is to connect the dots without

turning your brain into a worst-case-scenario vending machine.

Let’s break down what cysts are, what ovarian cancer is, where they overlap, and what doctors actually look for when

deciding whether a cyst is “watch and wait” or “let’s investigate.”

First things first: what counts as an ovarian cyst?

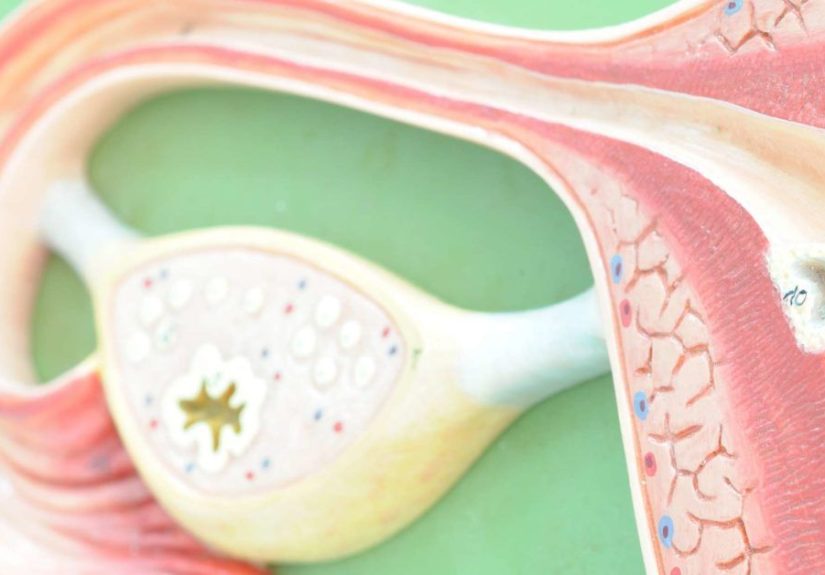

An ovarian cyst is a fluid-filled sac in or on an ovary. Many cysts form as part of the normal menstrual cycle

(ovulation). Think of them as “temporary construction zones” that usually pack up and leave without saying goodbye.

Common types of ovarian cysts

-

Functional (simple) cysts: The most common type. These include follicular cysts and corpus luteum

cysts that can happen around ovulation. They often resolve on their own. - Hemorrhagic cysts: A functional cyst that bleeds internally. Often painful, often still benign.

-

Endometriomas: Cysts associated with endometriosis (sometimes nicknamed “chocolate cysts” because of

old blood insidemedical folks really know how to make things sound like dessert and horror at the same time). -

Dermoid cysts (mature teratomas): Benign growths that can contain different tissue types. Weird? Yes.

Usually cancer? No. - Cystadenomas: Typically benign tumors that can be filled with watery or mucous-like fluid; can get large.

The key takeaway: “cyst” is a broad umbrella term. Some cysts are normal cycle-related; others are growths that deserve

a closer look based on appearance, symptoms, and your life stage.

What is ovarian cancer (and why does it get lumped into “cyst talk”)?

Ovarian cancer is cancer that involves the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or the lining of the abdomen (primary peritoneal cancer).

Clinically, these are often grouped together because they behave similarly and can be diagnosed and treated in similar ways.

Ovarian cancer is less common than many other cancers, but it can be serious because early symptoms can be subtle and easy to

blame on “life,” “stress,” or “that burrito from yesterday.”

So… do ovarian cysts cause ovarian cancer?

In most cases, no. The most common ovarian cystsespecially simple, functional cysts in people who

are still having periodsare not considered a direct cause of ovarian cancer.

The link people sense (and fear) usually comes from three realities:

1) Some cancers can look like “a cyst” at first

Ovarian cancer (and borderline tumors) can present as a cystic mass on imaging. In other words, a scan might show something

that’s partly fluid-filled, and the next step is figuring out whether it has features that suggest a benign cyst or something

more concerning.

2) Age changes the math

Ovarian cysts can happen at any age, but the chance that an ovarian mass is malignant generally increases after menopause.

That’s why a small, simple cyst in a 22-year-old is usually handled very differently than a complex-looking cyst in a

62-year-old.

3) Certain conditions raise ovarian cancer risk and also involve cysts

The biggest example is endometriosis. Endometriosis can cause ovarian cysts (endometriomas), and research suggests

endometriosis is associated with a higher risk of certain ovarian cancer subtypeswhile still keeping the overall lifetime risk

relatively low for most people.

Bottom line: most cysts are benign. The “link” is less about cysts turning into cancer overnight and more about

overlap in appearance, symptoms, and risk context.

Simple vs. complex cysts: the ultrasound clues that matter

Ultrasound is usually the first-line imaging test for ovarian cysts. When radiologists describe a cyst, they’re not trying to

write poetrythey’re giving a risk snapshot.

Features that often suggest a benign (lower-risk) cyst

- Simple appearance (fluid-filled, thin wall)

- No solid components

- No thick septations (internal “walls”)

- No papillary projections (little growths into the cyst space)

- Smaller size and stable appearance over time (context-dependent)

Features that can raise concern (especially after menopause)

- Solid areas within the mass

- Thick septations

- Papillary projections or nodules

- Increased blood flow in solid components (on Doppler imaging)

- Fluid in the abdomen (ascites) or signs the mass is affecting nearby structures

Many imaging teams also use structured risk systems (you may see terms like standardized categories in reports) to reduce

guesswork and guide follow-up. Translation: fewer “maybe-ish” reports, more “here’s what we recommend next.”

Symptoms: why cysts and ovarian cancer can feel confusingly similar

One reason this topic is stressful is that ovarian cyst symptoms and ovarian cancer symptoms can overlap. Both can cause pelvic

discomfort, bloating, or a feeling of pressure.

Symptoms more commonly linked with ovarian cysts

- Pelvic pain that comes and goes (often one-sided)

- Pain around your period

- Pain with movement or certain activities

- Sudden sharp pain (possible rupture or torsionmore on that below)

Symptoms that deserve attention if they are persistent or new

- Ongoing bloating or increased abdominal size

- Feeling full quickly or difficulty eating (early satiety)

- Pelvic or abdominal pain that doesn’t quit

- Urinary urgency or going more often without another clear reason

- Changes in bowel habits (constipation or diarrhea) that stick around

- Unexplained fatigue or weight changes

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding, especially after menopause

The big concept doctors emphasize is persistence. Everyone gets bloated sometimes. The concern rises when symptoms are

new for you, occur frequently, and don’t improve the way typical GI or cycle-related symptoms often do.

How doctors evaluate the “cyst vs. cancer” question

Clinicians don’t rely on a single clue. They combine your age, symptoms, physical exam, imaging details, and sometimes blood tests.

That’s not indecisionit’s pattern recognition with a safety net.

Step 1: History and risk context

Expect questions about:

- Age and whether you’re premenopausal or postmenopausal

- Personal history of breast, colorectal, or uterine cancer

- Family history of breast/ovarian cancer (especially first-degree relatives)

- Known genetic risks (BRCA mutations or Lynch syndrome)

- Endometriosis history

- New, persistent symptoms

Step 2: Pelvic ultrasound (often transvaginal)

Ultrasound helps sort likely benign cysts from masses that need closer evaluation. If the cyst looks simple and you’re low-risk,

the next step may simply be follow-up imaging.

Step 3: Blood tests (sometimes), including CA-125

CA-125 is a protein that can be elevated in many people with ovarian cancerbut it’s also elevated in a bunch of non-cancer

conditions (including endometriosis, fibroids, pelvic inflammation, and even normal variation). That’s why CA-125 is

not a reliable screening test for average-risk people and is interpreted differently depending on age and menopausal status.

In general, CA-125 is more informative after menopause when fewer benign conditions are likely to inflate it, but it still

can’t “diagnose” ovarian cancer by itself.

Step 4: Decide on monitoring vs. surgery vs. specialist referral

Many cystsespecially small, simple onesare managed with watchful waiting and repeat ultrasound. If a cyst is large,

painful, persistent, growing, or has suspicious features, surgical evaluation may be recommended.

If cancer is a significant concern, referral to a gynecologic oncologist matters because outcomes are often better when

suspected ovarian cancer surgery and staging are done by specialists trained in these procedures.

When an ovarian cyst is an emergency (yes, sometimes it is)

Most cysts are not urgent. A few situations are “don’t wait and see.”

Go get urgent care (or emergency care) if you have:

- Sudden, severe pelvic or abdominal pain (especially one-sided)

- Pain with nausea or vomiting (possible ovarian torsion)

- Fever with severe pain

- Fainting, dizziness, or signs of significant internal bleeding

Ovarian torsion (twisting of the ovary) can cut off blood supply and needs prompt treatment. Cyst rupture can also be intensely

painful and occasionally serious.

Higher-risk situations: what “more cautious” looks like

Doctors tend to be more cautious when:

- You are postmenopausal

- The cyst/mass is complex on ultrasound

- You have ascites or concerning findings beyond the ovary

- You have a strong family history or known genetic risk

- Symptoms are persistent and new

Cautious doesn’t always mean “it’s cancer.” It usually means “we’re not guessing; we’re verifying.”

Risk factors and protective factors: where cysts fit in (and where they don’t)

Ovarian cancer risk is influenced by genetics, age, reproductive history, and certain conditions. Most ovarian cysts are not

on the “cause list,” but some conditions associated with cysts can matter.

Risk factors commonly discussed

- Older age (risk rises as you get older, especially after menopause)

- BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations and Lynch syndrome

- Strong family history of breast/ovarian cancer

- Endometriosis (associated with increased risk for certain ovarian cancer subtypes)

- Obesity and certain hormonal/reproductive patterns (discussed case-by-case)

Protective factors often noted in research

- Oral contraceptive use (birth control pills) is associated with a lower risk of ovarian cancer

- Pregnancy and breastfeeding (often discussed as protective in population studies)

- Risk-reducing surgery for very high-risk individuals (a specialist decision)

Important: “protective” does not mean “guarantee,” and “risk factor” does not mean “destiny.” It’s probability, not prophecy.

Practical FAQs (because your brain is already asking)

Can a benign cyst turn into ovarian cancer?

Most functional cysts do not “turn into” cancer. The bigger clinical issue is that some ovarian tumors can be cystic or mixed

(part cyst, part solid), so the appearance guides whether follow-up is needed.

If I’ve had ovarian cysts, does that mean I’m high risk?

Not automatically. Many people have cysts at some point. Risk depends more on age, ultrasound features, persistence, symptoms,

and personal/family history.

Should everyone get CA-125 tests “just to be safe”?

For average-risk people without symptoms, routine CA-125 screening is not recommended because it can lead to false alarms and

unnecessary procedures. CA-125 is best used as part of an evaluation when there’s a specific reason, not as a fishing expedition.

What if my report says “complex cyst”?

“Complex” doesn’t automatically mean cancer. It means the cyst has features beyond a simple fluid-filled sac. The next steps may

include repeat ultrasound, additional imaging, blood tests, or surgical evaluation depending on your age and specific findings.

What about endometriomas?

Endometriomas are usually benign, but endometriosis has been linked to a higher risk of certain ovarian cancer subtypes.

That doesn’t mean most people with endometriosis will get ovarian cancermost won’t. It means follow-up and individualized care

matter, especially if symptoms change or imaging findings evolve.

What should I do if I’m worried right now?

If you have persistent symptoms (especially bloating, pelvic/abdominal pain, early satiety, urinary urgency/frequency), or you’ve

been told you have a complex cyst, book a visit with a clinician who can review your imaging and risk factors. If symptoms are severe

and sudden, seek urgent care.

Conclusion: the link in one sentence (okay, two)

Most ovarian cystsespecially simple, cycle-related cystsare benign and not a direct cause of ovarian cancer. The real “link” is that

ovarian cancer can sometimes appear as a cystic mass, and certain higher-risk contexts (like postmenopause, suspicious ultrasound features,

or endometriosis/genetic risk) deserve closer evaluation.

If you remember nothing else, remember this: your next step should be guided by patternspersistence of symptoms, imaging features,

and risk historynot panic. And yes, it’s okay to ask your clinician to explain the ultrasound report like you’re a smart human who just doesn’t speak

fluent Radiology.

Experiences people share (and what they often learn along the way)

The stories below are composite experiencesrealistic scenarios based on common clinical patterns and patient concerns. They’re included because facts are

helpful, but lived experience is often what makes the facts finally “stick.”

1) “I had a cyst and it disappearedso why was I so scared?”

A common experience is getting an ultrasound for cramps, irregular cycles, or pelvic pain and hearing, “You have a small cyst.”

Even when the clinician calmly explains that functional cysts are common, many people go home and Google themselves into a nervous spiral.

Then, a follow-up scan a few weeks or months later shows the cyst is gone. The lesson most people report: the word “cyst” feels huge,

but the reality is often routine. Many wish they’d been told up front what “watchful waiting” actually meansmonitoring for changes,

not ignoring the problem.

2) “My cyst was painful, but it still wasn’t cancer.”

Another frequent scenario: a hemorrhagic cyst causes sharp pain on one side, sometimes bad enough to send someone to urgent care.

The pain is real, the fear is real, and the ultrasound report may include scary-sounding phrases like “complex” or “internal echoes.”

Many people later learn that “complex” can describe blood or clots inside a benign cyst, not just tumors. Follow-up imaging often shows

the cyst shrinking as the body reabsorbs the blood. The take-home message they share: pain intensity doesn’t automatically predict cancer,

but it does deserve evaluationespecially if it’s sudden or severe.

3) “Endometriosis made everything feel murky.”

People with endometriosis often describe a long history of pelvic pain and fatigue. When an endometrioma is found, it can feel like,

“Greatanother thing.” Some report frustration because symptoms overlap with GI problems, bladder issues, and normal cycle changes, making

it hard to tell what’s “expected” versus “new.” The empowering shift tends to happen when they track symptoms (frequency and pattern) and

bring specific notes to appointments. Many also say it helped to hear the nuance: endometriosis is linked to a higher risk of certain ovarian

cancers, but the overall risk remains lowand individualized monitoring is the goal, not constant fear.

4) “After menopause, the conversation sounded differentand that was okay.”

Postmenopausal individuals often report that clinicians take ovarian cyst findings more seriously, even if the cyst is small.

This can be unsettling at first (“Why is everyone suddenly so concerned?”). But many later appreciate the clarity: after menopause,

the ovaries are less hormonally active, so new cysts are less likely to be functional. That doesn’t mean “it’s cancer,” but it does mean

the evaluation may include additional imaging, blood tests like CA-125, and sometimes surgical removalespecially if ultrasound shows

solid components or other concerning features. The lesson: a more cautious approach is about probabilities and prevention of missed diagnoses,

not a verdict.

5) “Persistent symptoms were the real signal, not a single test.”

Some people describe weeks to months of bloating, early fullness, pelvic discomfort, or urinary urgencysymptoms that were easy to dismiss

as stress, diet, aging, or “just life.” The turning point was often persistence: symptoms kept happening, didn’t respond to typical fixes,

or felt new and unusual. Many say they wish they’d sought care sooner not because they “should have known,” but because they didn’t realize

ovarian cancer symptoms can be vague. In evaluations, they also learn that no single blood test or ultrasound “proves” everything; clinicians

piece together the story from multiple clues. The most repeated advice from these experiences: trust persistence. If your body keeps raising

the same flag, it’s worth having someone investigate why.