Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Is a Sitemap?

- Why Sitemaps Matter for SEO

- Types of Sitemaps (and When to Use Each)

- What Should (and Shouldn’t) Go in Your Sitemap

- Sitemap Rules You Can’t Ignore

- How to Create a Sitemap

- Option A: Let your CMS generate it (recommended for most sites)

- Option B: Generate automatically (best for custom sites and big catalogs)

- Option C: Create manually (only for very small sites)

- Example: A basic XML sitemap

- Example: Sitemap index (when you have multiple sitemap files)

- About lastmod, changefreq, and priority

- How to Submit a Sitemap to Google (the right way)

- How to Submit a Sitemap to Bing

- Troubleshooting: Common Sitemap Problems (and How to Fix Them)

- Sitemap Best Practices That Actually Help (Not Busywork)

- Real-World Experiences: Sitemap Lessons From the Wild (Extra )

- Conclusion

If your website were a city, Google would be the tourist trying to see everything in one afternoon.

A sitemap is basically your “here’s the good stuff” mapminus the awkward folded-paper struggle.

Done right, it helps search engines discover your important pages faster, understand your site’s structure,

and avoid wasting time on dead ends.

What Is a Sitemap?

A sitemap is a file (or set of files) that lists the URLs on your site you want search engines to know about.

Depending on the format, it can also include helpful signals like when a page was last meaningfully updated,

or extra details for images, videos, and news content.

XML vs. HTML: Same Name, Different Jobs

People use “sitemap” to mean two things:

-

XML sitemap: Built for search engines. Usually lives at something like

/sitemap.xmlor/sitemap_index.xml. - HTML sitemap: Built for humans. It’s a navigational page that can help users (and sometimes crawlers) find key sections.

If you’re doing SEO, the XML sitemap is the must-have. The HTML version is optional, like sprinkles:

fun, sometimes useful, but not the foundation of the sundae.

Why Sitemaps Matter for SEO

A sitemap won’t magically make a low-quality page rank (sorry), but it can make discovery and crawling more efficient

which can absolutely impact how quickly and how completely your content gets indexed.

Sitemaps help most when…

- Your site is large (lots of pages, lots of categories, lots of “how did we even get here?” navigation).

- Your content is new and you want search engines to find it sooner.

- You have orphan pages (pages not well-linked internally).

- You publish media content (images, videos) or specialized content types.

- Your internal linking is still a work in progress (aka: “we’ll fix it after launch,” which is a famous last sentence).

Important reality check: submitting a sitemap is a hint, not a guarantee.

Google may choose not to crawl every URL listed, and it may not index everything it crawls.

Think of a sitemap as an invitation, not a subpoena.

Types of Sitemaps (and When to Use Each)

Not all sitemaps are created equal. Choose based on your site and what you publish.

1) XML Sitemap (the main character)

XML sitemaps are the most versatile. You can list URLs and optionally include metadata like lastmod

(last modified). You can also use extensions for images, video, news, and localized versions.

2) RSS/Atom Feed as a Sitemap (the “easy button” for blogs)

If your CMS automatically generates RSS or Atom feeds, you can submit those as sitemaps. This can be especially handy

for sites that publish frequently, because feeds often reflect recent content without extra work.

3) Text Sitemap (simple, no-frills)

A text sitemap is literally a plain text file with one URL per line. It’s simple and scalable, but limited to listing URLs.

What Should (and Shouldn’t) Go in Your Sitemap

The best sitemap is clean, accurate, and focused on URLs you actually want indexed.

The fastest way to make a sitemap less useful is to treat it like a junk drawer.

Include:

- Canonical URLs you want to show in search results.

- Indexable pages (no

noindextags, no blocked access). - Final destination URLs (avoid listing redirecting URLs whenever possible).

- 200-status pages that load for search engine crawlers without login walls.

Exclude (usually):

- Admin pages, staging URLs, and “test-test-final-REAL-final” environments.

- Pages blocked by

robots.txtor protected behind authentication. - Duplicate variants (session parameters, sort/filter combos, tracking URLs).

- Search results pages, thin tag pages, and low-value faceted navigation (unless you intentionally want them indexed).

Canonicals: Your Sitemap Should Agree With Them

If a page’s canonical tag points to a different URL, listing the non-canonical URL in your sitemap sends mixed signals.

When Google has to choose between conflicting instructions, your site usually doesn’t win the argument.

Align your sitemap entries with your canonical strategy.

Sitemap Rules You Can’t Ignore

Size limits (yes, there are rules)

Each sitemap file has practical limits. If your site is big, you’ll split your URLs across multiple sitemap files

and use a sitemap index to organize them. You can also compress sitemaps (commonly .gz)

to make transfer more efficientbut the uncompressed size limits still matter.

Location and scope

Host your sitemap in a place that makes senseideally at the root of your sitebecause sitemap location can affect

which URLs it’s considered “responsible” for unless you submit through Search Console.

Use absolute URLs and UTF-8

Sitemaps should use fully-qualified absolute URLs (not relative paths) and be properly encoded (UTF-8).

Keep it clean, standard, and boringin the best way.

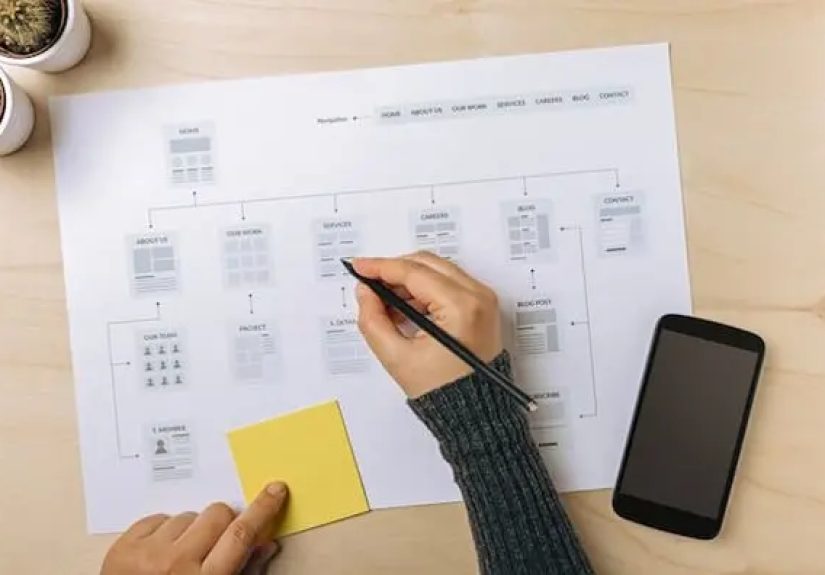

How to Create a Sitemap

There are three common approaches. Pick the one that matches your platform and site size.

Option A: Let your CMS generate it (recommended for most sites)

-

WordPress: WordPress can generate a basic sitemap (commonly at

/wp-sitemap.xml).

Many site owners use SEO plugins (like Yoast, Rank Math, or AIOSEO) for more controlespecially to exclude

low-value URLs, handle large sites, or support richer media SEO. -

Shopify: Shopify automatically generates an XML sitemap at

/sitemap.xml.

It typically includes links to separate sitemaps for products, collections, pages, and blog posts. -

Other platforms: Many hosted builders generate sitemaps automatically. The main job becomes finding the URL

and confirming it’s accessible.

Option B: Generate automatically (best for custom sites and big catalogs)

If your site is custom-built or extremely large, generating sitemaps from your database is often the best approach.

Typical workflow:

- Query your database for canonical, indexable URLs.

- Split into multiple sitemap files if you exceed practical limits.

- Create a sitemap index file that lists each sitemap file.

- Host them at stable URLs (don’t rename them every week unless you enjoy chaos).

- Update on a schedule or event trigger (e.g., when new products publish).

Option C: Create manually (only for very small sites)

If you have a few dozen pages, manual creation can workespecially with a text sitemap.

But once your site grows, manual maintenance becomes a full-time job… that pays in tears.

Example: A basic XML sitemap

Example: Sitemap index (when you have multiple sitemap files)

About lastmod, changefreq, and priority

Here’s the practical truth:

-

lastmodcan be usefulif it’s consistently accurate and reflects meaningful page updates

(not just changing a footer year). -

changefreqandpriorityare often ignored by Google, so don’t spend hours “tuning” them like a race car.

Put that energy into content quality and internal linking instead.

How to Submit a Sitemap to Google (the right way)

The most common method is Google Search Console. This lets you see submission history, processing status,

and any parsing or fetch errors.

Step-by-step: Google Search Console submission

- Verify your site in Google Search Console (ownership verification is required to submit sitemaps there).

- In the left navigation, open Sitemaps.

-

Enter your sitemap URL (example:

sitemap.xmlorsitemap_index.xml) and click Submit.

Note: you’re not uploading a filejust telling Google where it lives. - Watch the status. If you see errors, click into the sitemap details to find what’s wrong (fetch issues, invalid URLs, formatting problems, etc.).

- Be patient. Crawling and indexing take time, and Google may not crawl everything listed immediately.

Bonus method: Add your sitemap to robots.txt

You can also list your sitemap location in your robots.txt file. This is a clean “here it is” sign for crawlers.

Skip the old “ping” trick

If you’ve seen advice to “ping Google” every time your sitemap updates, you can retire that idea with honor.

Modern best practice is: keep your sitemap accessible, keep it accurate, submit through Search Console when needed,

and maintain solid internal links so crawlers can naturally discover updates.

How to Submit a Sitemap to Bing

Bing still mattersespecially for certain audiences and for visibility across Microsoft ecosystems.

The process is straightforward:

- Open Bing Webmaster Tools and add your site.

- Verify ownership (similar idea to Google).

- Find the sitemap submission area (often labeled Sitemaps or Submit sitemap).

- Submit your sitemap URL (example:

https://www.example.com/sitemap.xml). - Monitor for errors and indexing signals, just like you do in Google Search Console.

Troubleshooting: Common Sitemap Problems (and How to Fix Them)

When sitemaps fail, they tend to fail in predictable ways. Here are the usual suspects:

1) “Couldn’t fetch”

- The sitemap URL is wrong (404).

- The server blocks crawlers or requires login.

- Your

robots.txtaccidentally blocks the sitemap URL (yes, this happens more than you’d think). - Temporary server issues or timeouts.

2) Parsing errors

- Invalid XML syntax (missing tags, broken encoding, bad characters).

- Invalid dates (use proper date formats).

- Wrong namespaces or incorrect sitemap structure.

3) “Submitted URL not allowed” or mismatched site versions

This often happens when your property is https://example.com but your sitemap lists http://,

or mixes www and non-www. Keep the sitemap URLs consistent with your preferred canonical version.

4) Low-quality or non-indexable URLs inside the sitemap

If your sitemap is stuffed with redirects, noindex pages, blocked URLs, or thin pages, you’re basically handing Google a list of chores.

Clean the sitemap so it reflects what you actually want crawled and indexed.

Quick debugging checklist

- Open the sitemap URL in your browser. Does it load? Is it readable? (You should see XML, not an error page.)

- Confirm it returns a 200 status and isn’t blocked by login or IP rules.

- Validate the XML structure (especially if you generate it yourself).

- Confirm listed URLs are canonical and indexable (no redirects, no

noindex, no robots blocks). - Re-check Google Search Console’s sitemap report for the exact error message and affected URLs.

Sitemap Best Practices That Actually Help (Not Busywork)

Keep it “clean and mean”

A sitemap is most helpful when it’s curated. Include what matters: your important pages, your category hubs,

your product pages (for e-commerce), your evergreen articles, and your core conversion pages.

Segment big sites

For large websites, split sitemaps by type: pages, posts, products, categories, videos, images, and so on.

It’s easier to debug, easier to manage, and easier to understand what’s being crawled.

Use lastmod honestly

If you update lastmod every day for every URL, Google will eventually treat it like “the boy who cried update.”

Only change it when the page changes in a meaningful way (main content, structured data, important links).

Don’t treat sitemaps as a substitute for internal linking

A sitemap is helpful, but a strong internal linking strategy is the real MVP. Think topic clusters,

smart navigation, breadcrumbs, and contextual links that make sense for humans (and, conveniently, crawlers).

Remember: order doesn’t save you

You don’t need to obsess over the order of URLs in your sitemap. Focus on including the right URLs and keeping the file accessible and valid.

Real-World Experiences: Sitemap Lessons From the Wild (Extra )

On real websites, sitemaps are rarely the problem you start withand surprisingly often the problem you end with.

Not because sitemaps are complicated, but because they faithfully expose whatever chaos is happening under the hood.

In other words: sitemaps don’t create messes. They just shine a flashlight into the basement.

One common “experience” teams run into is the faceted navigation explosion. Picture an e-commerce store with filters:

size, color, brand, price range, shipping speed, and “only show items that match my vibe.” If the site generates crawlable URLs

for every filter combo, you can end up with thousands (or millions) of near-duplicate pages. Then someone plugs a sitemap generator

into the database andboomyour sitemap becomes a list of every possible shopping mood swing.

The fix is usually a mix of strategy and restraint: decide which category/filter pages deserve indexing, canonicalize or noindex the rest,

and ensure your sitemap only includes the pages you truly want discoverable.

Another classic: the staging site leak. A developer spins up staging.example.com, a sitemap gets generated automatically,

and suddenly search engines learn about URLs that were never meant to see daylight. Sometimes the staging environment is blocked correctly,

sometimes it isn’t, and sometimes it’s blocked for users but not for crawlers (because the universe has a sense of humor).

The practical habit that prevents this is simple: treat staging environments as “private by default,” and confirm that sitemaps

are only public on the production domain.

Then there’s the “Why isn’t Google indexing my pages?” momentusually followed by discovering that the sitemap

is full of 301 redirects, 404 pages, or URLs that are tagged noindex. This happens when a site migrates,

slugs change, or trailing slashes get rewritten. Sitemaps don’t automatically “know” you changed your mind; they only know what you publish.

A strong routine here is to regenerate your sitemap after major changes and do a quick spot-check:

pick 10 URLs from the sitemap and confirm they load with a 200 status, are canonical to themselves, and are indexable.

It’s not glamorous, but neither is debugging sitemap errors at 2 a.m.

A more subtle experience shows up on content-heavy sites: pages that exist but aren’t important.

Tag archives, internal search pages, thin author pages, and empty category pages can quietly dominate your sitemap

if you don’t configure exclusions. The end result is that search engines spend attention on pages that don’t earn it,

while your best articles wait in line behind “Tag: Uncategorized.” The smartest move is to define what “index-worthy” means

for your site (unique value, search intent, quality depth, conversion purpose) and make the sitemap reflect that.

Finally, the most underrated experience: sitemaps become a diagnostic tool. When your sitemap is clean,

it’s easier to spot real indexing patterns. When it’s noisy, everything looks like a problem. Many teams discover that once the sitemap is fixed,

Search Console reporting becomes more actionable: fewer confusing errors, clearer trends, and faster feedback loops when new content launches.

In practice, a good sitemap won’t replace great content or strong authoritybut it will keep the technical side from tripping you

right as you’re about to cross the finish line.