Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Is TFINER, Exactly?

- Why It Looks Like a Solar Sail (and Why That’s Not Just Aesthetic)

- How TFINER Makes Thrust: A “Sail” That’s Also the Engine

- Solar Sail vs. TFINER: Same Shape, Different Physics

- The Missions That Make People Pay Attention

- The Hard Parts (a.k.a. “The Universe Doesn’t Hand Out Free Delta-V”)

- The Atompunk Factor: Why This Thing Feels Like Retro-Future Space Art

- So… Is TFINER a Solar Sail Copycat?

- 500-Word Experiences Section: What It Feels Like to Think Through a TFINER Mission

- Conclusion

If you’ve ever seen a solar sail, you know the vibe: a big, whisper-thin sheet that looks like it should be

powering a spaceship in a 1957 comic book where everyone wears a turtleneck and somehow never spills coffee

in zero-G. Now meet TFINERa NASA-funded propulsion concept that looks like a solar sail,

but isn’t trying to catch sunlight the way a kite catches wind.

TFINER is more like an atompunk magic trick: it carries its own “push” inside the sail itself, using the

momentum of radioactive decay to generate a continuous, gentle thrust over a long time. That’s the reason

it’s being discussed as a potential path to missions that are currently stuck in the “cool idea, see you in

the next century” categorylike chasing down a fast interstellar visitor or repositioning a telescope far

beyond the planets.

What Is TFINER, Exactly?

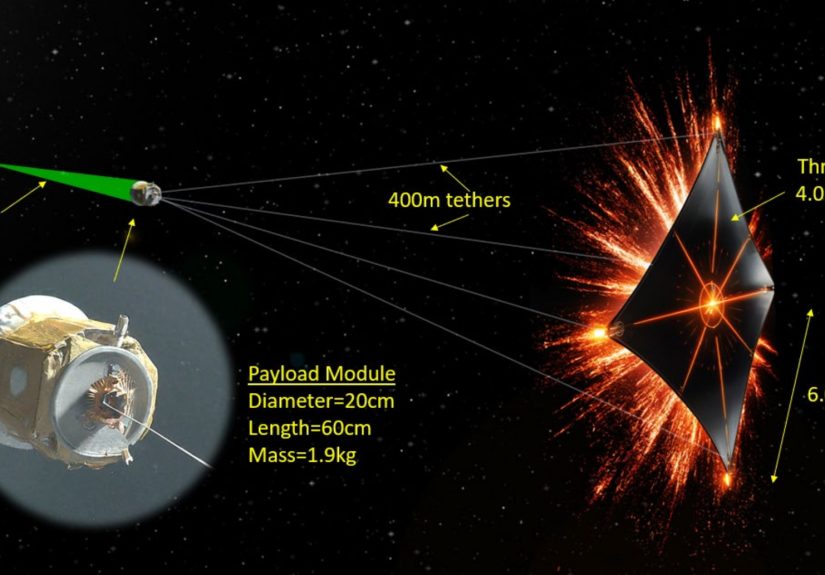

TFINER stands for Thin Film Isotope Nuclear Engine Rocket. It’s a concept supported

through NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) programmeaning it’s early-stage, high-upside research,

not a flight-ready system sitting in a warehouse waiting for a launch date.

The core idea is disarmingly simple: make ultra-thin sheets of a radioactive isotope, and use the momentum of

its decay products to push the spacecraft. It’s “rocket” propulsion in the sense that something is being

thrown out the back (decay particles), but the hardware looks like a sail because the propulsion surface is

a big, flat sheet.

Quick translation from space-nerd to human

- Solar sail: sunlight hits a reflective sheet → tiny push → big speed over time.

- TFINER: radioactive decay ejects particles → tiny push → big speed over time.

- Shared trait: low thrust, long duration, and the patience of a saint.

Why It Looks Like a Solar Sail (and Why That’s Not Just Aesthetic)

Solar sails are big because photon pressure is small. To get useful acceleration, you maximize area while

keeping mass low. TFINER follows the same logic: it’s aiming for high performance through large area,

low mass, continuous thrust. In practice, that pushes you toward thin sheets and lightweight support

structuresexactly what makes it look like a solar sail.

But the resemblance isn’t just visual. In mission-planning terms, both systems play the same long game:

you don’t “burn” for minutes; you “burn” for months or years. You don’t stomp the gas pedal; you gently

lean on it until the universe gives up and lets you pass.

How TFINER Makes Thrust: A “Sail” That’s Also the Engine

One of the key challenges is that radioactive decay is naturally isotropicparticles shoot out in all

directions. If you just slapped a radioactive coating on a sheet, you’d get equal push forward and backward

(plus an exciting new way to ruin everyone’s day).

TFINER’s trick is to bias the direction of the momentum so more of it contributes to thrust in

one direction. The baseline idea uses thin-film radioisotopes and a substrate/absorber layer to capture

particles going the “wrong” way.

The thin-film concept (the part that sounds fake but isn’t)

The baseline design described publicly uses a very thin layer of a radioisotope (often discussed as

Thorium-228) and relies on alpha decay. Because the layer is extremely thin, a good portion of

alpha particles can escape from the “exhaust” side. Meanwhile, the opposite side includes an absorber layer

intended to stop particles that would otherwise cancel the net thrust.

The reason Thorium-228 gets mentioned is that it sits in a decay chain that can produce multiple alpha

emissions over time. In plain terms: it’s not just one little shovethere can be a series of shoves as

daughter products decay, which may improve overall performance.

Continuous thrust, low drama (and yes, very low thrust)

TFINER isn’t trying to win drag races. It’s aiming for steady acceleration over long durations.

The result can be large total velocity change (delta-v) over timeeven if the day-to-day acceleration feels

like the spacecraft is being pushed by a polite ghost.

In NIAC materials, the concept is discussed in the neighborhood of ~100 km/s velocity change for

simpler architectures, with more advanced designs potentially going beyond that. Those are huge numbers by

conventional spacecraft standards, but they come from patient, continuous thrust rather than brute force.

Steering: “You can turn it”… just don’t expect Tokyo Drift

A sail-shaped engine raises an obvious question: how do you point the thrust where you want it?

Public descriptions mention approaches like sheet reconfiguration (changing how thrust sheets are

arranged or oriented) and enabling active thrust vectoring to support maneuvers rather than only

straight-line acceleration.

This matters because some of the most interesting targetslike fast interstellar objectsrequire

searching and course correction in deep space, not just a one-shot flyby on rails.

Solar Sail vs. TFINER: Same Shape, Different Physics

Let’s put the “lookalike” debate to rest. If solar sails are powered by sunshine, TFINER is powered by

nuclear decay momentum. Here’s how that shakes out.

-

Energy source: Solar sails depend on sunlight intensity (strong near the Sun, weaker far out).

TFINER carries its energy source with it, so it can keep providing thrust in deep space. -

Thrust control: Solar sails can tack and trim like a sailboat, using orientation to change the

direction of photon pressure. TFINER concepts discuss ways to bias thrust direction and vector it, but

the control story is still part of the research journey. -

Risk profile: Solar sails are mostly “just” big, delicate structures. TFINER adds the joys of

handling radioisotopes, shielding, containment, and public acceptance.

A fun historical note: solar sails aren’t just sci-fi wallpaper anymore. We’ve seen real demonstrations,

including The Planetary Society’s LightSail projects and NASA’s technology work on advanced solar sails.

Solar sailing is no longer “if,” it’s “how well can we scale and control it?”

The Missions That Make People Pay Attention

The reason TFINER gets airtime isn’t because it looks cool (though it definitely does). It’s because it’s

pitched as a tool for missions that struggle with today’s propulsion options.

1) Chasing an interstellar object (the “don’t blink” problem)

When ‘Oumuamua passed through our solar system in 2017, it moved quickly and left quickly. With conventional

propulsion, catching up is brutally hard. TFINER is discussed as a way to build a spacecraft that can

accelerate to very high speeds and potentially reach such an object in a timeframe that resembles a career,

not a geological epoch.

2) The solar gravitational lens (the “telescope so far away it needs snacks” problem)

The Sun’s gravity can act like a lens, focusing light and potentially enabling extremely powerful imaging

if you place a telescope far out along the gravitational focal line. The challenge is getting there and

being able to maneuver once you arrive. NIAC descriptions highlight TFINER’s potential to both reach such

distant regions faster and reposition to observe multiple targets.

3) Deep-space maneuvering where solar sails fade

Sunlight gets weaker with distance. Solar sails can still work far out, but the thrust drops. Because TFINER

carries its thrust mechanism onboard, it’s discussed as a way to keep meaningful propulsion available after

years in deep spaceexactly where many ambitious missions get bogged down.

The Hard Parts (a.k.a. “The Universe Doesn’t Hand Out Free Delta-V”)

If TFINER were easy, you’d already have a Kickstarter for the “Atompunk Explorer Deluxe Edition” (now with

free cosmic rays!). The concept faces real engineering and programmatic challenges.

Radioisotope production and handling

The propulsion depends on producing and processing specific isotopes, and doing so at quantities and purities

compatible with a flight system. It also has to fit within real-world safety standards for launch approval,

ground operations, and containment in worst-case scenarios.

Thin-film manufacturing at serious scale

Making ultra-thin layers is one thing in a lab; making large-area, durable sheets that survive deployment,

micrometeoroid exposure, thermal cycling, and years of operation is a whole different sport. The “sail”

has to be both delicate (thin enough for particles to escape) and stubborn (strong enough to stay intact).

Radiation, shielding, and spacecraft layout

Using radioactive decay as propulsion means you have to think carefully about how the spacecraft protects

sensitive electronics and instruments. That affects geometry, distance, materials, and operational modes.

In other words: the sail might look like a clean sci-fi sheet, but the spacecraft bus will be having a very

serious conversation with physics.

Thrust is small, so navigation needs to be smart

With low thrust, trajectories are sensitive to small errors over long time periods. That means high-quality

navigation, careful mission planning, and realistic expectations. TFINER may offer big cumulative speed, but

it won’t rescue sloppy guidance like a last-second rocket burn can.

The Atompunk Factor: Why This Thing Feels Like Retro-Future Space Art

“Atompunk” is basically the future as imagined through mid-century Atomic Age optimismchrome, geometry,

bold silhouettes, and a dash of “what if nuclear power solved everything?” A sail-shaped nuclear engine is

practically an atompunk bingo card:

- Big, shiny surfaces that look like they belong near neon signs and dramatic angles.

- Nuclear-driven ambitionthe Atomic Age belief that enormous problems can be handled with

enough clever engineering (and perhaps a slide rule). - Space-race energybecause nothing says “we’re going places” like a sail that’s also a reactor’s

weirder cousin.

Solar sails already look like retrofuturism made real. TFINER takes that silhouette and adds a nuclear

propulsion twistturning the “sail” from a passive reflector into an active momentum machine. That’s why

the phrase “atompunk solar sail lookalike” lands so well: it describes both the appearance and the vibe.

So… Is TFINER a Solar Sail Copycat?

Visually? Absolutely. Functionally? Not really.

Solar sails are powered by the environment (sunlight). TFINER is powered by its own fuel (radioisotopes).

Both are long-duration, low-thrust propulsion approaches built around lightweight area. They’re like two

different musical genres sharing the same instrument: one is acoustic sunlight folk; the other is nuclear

jazz played very quietly for a very long time.

500-Word Experiences Section: What It Feels Like to Think Through a TFINER Mission

Most “experiences” around TFINER today happen in a place we don’t talk about enough: the brain of anyone who

tries to plan a mission when the propulsion system is basically a whisper that never stops. If you’re used to

chemical rockets, your intuition screams for a dramatic burnbig thrust, short time, fireworks. With TFINER,

the fireworks are replaced by a calendar invite titled “Acceleration: ongoing.”

One of the first mental shifts is learning to celebrate tiny numbers. You start thinking in “today’s

acceleration” the way people talk about daily steps. Did we get a little push today? Great. Do that again for

a year. Then two years. Then suddenly you’re talking about speeds that make conventional mission planners

squint and ask, “Wait, you did what with how much fuel?”

The next experience is realizing how sail-like engineering problems keep sneaking back in. Even though TFINER

isn’t catching photons, it still wants a huge, thin surface. That means deployment anxieties, structural

stability worries, and the general fear that your beautiful sheet will behave like a stubborn bedsheet in a

windy parking lotexcept the parking lot is space, and the wind is thermal cycling and micrometeoroids.

People who’ve watched solar sail demonstrations tend to nod knowingly here: the propulsion physics may differ,

but “big, thin, deployed structure” is its own boss fight.

Then there’s the experience of designing around radioactivity without turning the mission into a PR disaster.

Even if the engineering case is solid, you have to picture launch approval reviews, safety documentation, and

the very real need to communicate what the system is (and isn’t). That’s a different kind of challenge: not

just “can we build it,” but “can we build it in a way that’s responsibly testable and publicly acceptable?”

In practice, this often means thinking in layerscontainment, redundancy, fault tolerance, and what happens if

something goes wrong at the worst possible time.

Finally, the most satisfying “experience” is the daydream moment when the trajectory starts to make narrative

sense. You picture a spacecraft leaving the inner solar system, still accelerating when most probes are

already coasting. You imagine it adjusting course out where sunlight is dim and chemical propellant is long

gone. And you picture it doing something we almost never get to do: arriving at a target that’s actively

trying to get away. Whether that target is an interstellar visitor or a far-off observation line for a

gravitational lens telescope, the emotional payoff is the sameTFINER is the kind of idea that makes space

feel big, but not unreachable. It turns “we can’t” into “we might, if we’re clever and patient.”

Conclusion

TFINER earns its “atompunk solar sail lookalike” nickname because it blends two things that rarely share the

same silhouette: the elegant, sheet-like geometry of solar sailing and the nuclear bravado of Atomic Age

propulsion dreams. It’s not a finished spacecraft, and it’s not a guaranteed future. But it’s a serious,

NIAC-supported attempt to answer a question that keeps coming back in space exploration:

How do we go faster, farther, and still maneuver when we get there?

If TFINER (or something like it) ever flies, it won’t just be a new engineit’ll be a new kind of patience.

And honestly, that’s the most atompunk thing of all: believing the future is worth building, even if it takes

a long time to get there.