Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Carlson Was Responding To: A Real Debate With Real Consequences

- QE, Bailouts, and the Uncomfortable Truth: Crisis Policy Is a Trade-Off Machine

- Why “The Alternative” Could Have Been WorseEspecially for Younger Adults

- So Why Do Younger Generations Still Feel Like They Got the Short End?

- The Personal Finance Translation: “Better Than the Alternative” Is Not the Same as “Good”

- What Investors Can Control When the World Won’t Stop World-ing

- Conclusion: The Point Isn’t That Everything Was Fine

Every generation gets at least one “you had to be there” economic event. For many millennials, the Great Recession wasn’t just a headlineit was the

background music of early adulthood. Jobs were scarce, paychecks were timid, and the “American Dream” started to feel like a subscription service that

had quietly doubled in price.

In a 2019 post on A Wealth of Common Sense, Ben Carlson tackled a hot take that pops up whenever people debate the Federal Reserve’s crisis response:

sure, extraordinary policy may have pumped up asset prices and widened frustrationsbut what, exactly, was the alternative? His thesis was blunt, almost

annoyingly so (in a useful way): the alternative was worse. Not “perfect,” not “fair,” not “fun.” Just… worse.

This idea matters because it shows up everywhere in personal finance. It’s the same logic that says, “I don’t love paying for insurance, but I love going

bankrupt even less.” It’s the same logic that says, “I’d prefer lower home prices, but I’d also prefer not to job-hunt in an economy that’s on fire.”

And it’s the same logic investors need when markets get ugly: “I don’t like volatility, but I like panic-selling at the bottom even less.”

What Carlson Was Responding To: A Real Debate With Real Consequences

Carlson’s post was sparked by commentary suggesting that quantitative easing (QE)the Fed’s large-scale asset purchaseshelped inflate asset prices,

benefiting older generations who already owned homes and stocks, while younger adults felt priced out. That complaint is not imaginary. When asset prices

rise faster than incomes, people who already own assets feel wealthier, while people trying to buy in feel like the bouncer just raised the cover charge.

Carlson didn’t deny the frustration. He argued the “who benefited?” story is incomplete without the “what did it prevent?” story. In his view, the Fed

was trying to avoid a much deeper collapsesomething closer to a full-blown depressionespecially when fiscal policy (Congress and the administration)

wasn’t delivering enough support to households at the scale many economists believed was needed.

QE, Bailouts, and the Uncomfortable Truth: Crisis Policy Is a Trade-Off Machine

QE in plain English

QE (often discussed as “large-scale asset purchases”) is the Fed buying longer-term securitieslike Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securitiesto push

down longer-term interest rates and ease financial conditions when short-term rates are already near zero. The goal is to make borrowing cheaper, stabilize

markets, and reduce the risk of a downward spiral where failing credit markets drag the real economy down with them.

This matters for regular people because “long-term rates” aren’t an abstract conceptthose rates influence mortgages, business loans, and a lot of the

financing behind hiring and investment decisions. Lower rates can support home purchases and refinancing, and can help keep credit flowing when lenders

are otherwise tempted to hide under their desks.

Bailouts weren’t one thing

“Bailout” became a catch-all word in the late 2000s, but it covered a bunch of programs with different targets: stabilizing banks, preventing runs,

supporting credit markets, and (in some cases) trying to reduce avoidable foreclosures. Some programs were repaid; some carried costs; all were

politically radioactive. The anger wasn’t just about numbersit was about who got rescued quickly versus who got rescued slowly (or not at all).

Why “The Alternative” Could Have Been WorseEspecially for Younger Adults

Here’s the key point Carlson emphasized: even if you believe asset prices rose in ways that benefited older owners, a deeper collapse would have punished

younger adults in ways that are easy to underestimate in hindsight. Lower home prices sound great until you remember what often comes with them in a crisis:

job losses, tighter credit, and a whole lot of “sorry, we froze hiring” emails.

1) Unemployment is the ultimate affordability killer

The U.S. unemployment rate peaked at around 10% in October 2009 during the Great Recession. That’s with aggressive policy responses. In a worse scenario,

unemployment could have gone higher and stayed high longer. And “affordable” homes aren’t very useful if your income disappears or your industry evaporates.

It’s hard to buy a house (or a diversified portfolio of anything) with a résumé and good vibes.

2) Credit can tighten even when interest rates fall

People often assume a crash means “rates go down, therefore mortgages get cheaper.” But in real crises, lenders don’t just price loansthey ration them.

Underwriting can become brutal. Down payments get bigger. Documentation requirements multiply like rabbits. And lenders get choosier about who is “safe.”

In other words: even if benchmark rates are low, the mortgage you personally qualify for might not be.

3) Lower prices can harm retirees, pensions, and the broader labor market

A deeper collapse would have hit not only wealthy investors but also workers with retirement accounts and pensionsplus older adults trying to retire on

portfolios tied to financial markets. If more older workers are forced to delay retirement, that can ripple into the labor market, potentially slowing

opportunities for younger workers. This is not a moral argument; it’s a plumbing argument. The economy is connected, and pain travels.

The “cheaper assets” version of a crisis is only a win if you still have income, cash flow, and access to credit when those assets are on sale.

So Why Do Younger Generations Still Feel Like They Got the Short End?

“The alternative was worse” doesn’t magically erase the legitimate reasons many younger adults are frustrated. Carlson acknowledged that people perceived

the system as protecting financial institutions more effectively than households. That perception was reinforced by painful lived experiences: foreclosures,

uneven recoveries, and the sense that the rules are different depending on how expensive your suit is.

Housing affordability didn’t just get worseit got weird

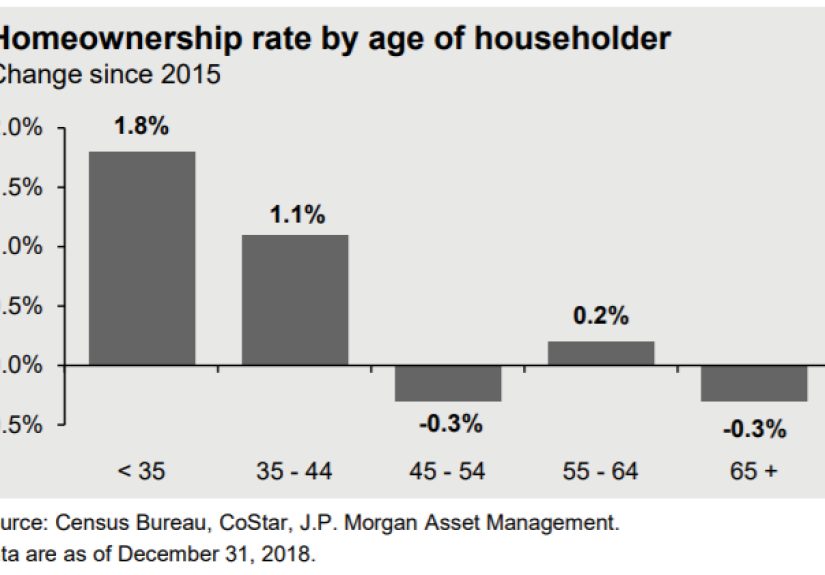

Even long after the Great Recession, housing affordability remained a major pressure point. Recent research from JPMorganChase’s Institute describes how

affordability worsened sharply from 2019 to 2024 as home prices and interest rates rose relative to incomes, estimating that to buy a comparable home,

households would have needed to devote substantially more of their budget to mortgage payments by late 2024.

Meanwhile, data on homeownership and first-time buying show how delayed the pathway has become. In 2025, the National Association of Realtors reported a

historically low share of first-time buyers and a higher median first-time buyer agebasically, the starter home timeline now comes with a “please allow

10–15 business years for processing” banner.

Student debt and delayed household formation add friction

Student debt isn’t the only factor, but it can make saving for a down payment and qualifying for a mortgage harder. And the broader “adulting schedule”

has shifted: more young adults live with parents longer than in some previous eras, often because it helps financially. That can be a smart moveyet it’s

also a signal that the cost of launching adulthood is higher than many people expected.

Wealth inequality is measurableand emotionally loud

The Federal Reserve publishes distributional wealth data that show how household wealth is spread across groups and over time. Even without arguing about

causes, the visibility matters: when people can see wealth concentrating, it shapes politics, expectations, and trust. And when trust drops, every policy

choice starts sounding like a conspiracy instead of a trade-off.

The Personal Finance Translation: “Better Than the Alternative” Is Not the Same as “Good”

Carlson’s point can be summarized like this: the Fed’s actions may have produced uncomfortable side effects, but allowing a depression-like collapse would

likely have produced even more damaging outcomesespecially for people early in their careers.

That logic doesn’t require you to be a Fed superfan. You can believe two things at the same time:

- Policy choices can be imperfect (and sometimes unfair in effect).

- Some alternatives can be worse (even if they sound emotionally satisfying in a slogan).

It’s the financial equivalent of saying: “Yes, the medicine has side effects. No, drinking from the puddle behind the pharmacy is not the superior plan.”

What Investors Can Control When the World Won’t Stop World-ing

One of the sharpest takeaways from Carlson’s post is the pivot from macro blame to micro control. You can argue about the Fed, Congress, banks, and

generational fairness for hours (and people do). But your financial outcomes still depend heavily on what you do consistently over time.

Build shock absorbers before you need them

An emergency fund is boringgloriously, beautifully boring. It’s the difference between “market downturn” and “market downturn plus I can’t pay rent.”

The bigger your cash buffer, the less likely you are to sell long-term investments at exactly the wrong time.

Don’t confuse “prices are down” with “it’s easy to buy”

In downturns, the best opportunities often appear when the headlines are the scariest. But the ability to take advantage of lower prices depends on your

job stability, your debt load, and whether you have dry powder (cash flow) to invest. That’s why risk management matters more than prediction.

Market timing is a seductive hobby with an expensive membership fee

Major investing firms have repeatedly shown how missing just a handful of strong market days can meaningfully reduce long-term results. The painful twist

is that some of the best days tend to cluster around some of the worst daysmaking “I’ll jump out for a bit” a strategy that often backfires.

A more durable approach is painfully unsexy: diversify, keep costs low, invest regularly, and rebalance when needed. It won’t impress anyone at a party,

but neither will bragging about your perfectly timed exit right before a rebound that never came.

Conclusion: The Point Isn’t That Everything Was Fine

“The alternative was worse” is not a victory lap for the system. It’s a reminder that crisis decisions are often made between bad and worse, not between

bad and perfect. Carlson’s argument (and the broader data since) suggests that the deeper lesson for households is this: prepare so you’re not

forced into terrible choices when the economy turns.

If you’re building wealth todayespecially if you’re younger or feel behindyour edge won’t come from winning arguments about the past. It comes from

stacking small, controllable wins: saving consistently, keeping debt manageable, investing with discipline, and building a career that can survive a rough

patch. Because when the next crisis arrives (they always RSVP), you want options.

Experience Appendix: Real-Life Trade-Offs You Can Relate To

The phrase “the alternative was worse” can sound abstract until you see how it plays out in everyday money decisions. Below are a few composite, real-world

style experiencespatterns people commonly reportshowing why a “cheaper prices” fantasy can collide with reality when the economy is stressed.

1) The would-be homebuyer who waited for the ‘perfect crash’

A young couple decides in 2018–2019 that housing is “too expensive” and vows to wait for the next downturn. They’re not wrong that prices feel stretched.

Then a shock hits the economy. For a brief window, listings sit longer and sellers get nervous. But the couple’s situation also changes: one person’s hours

are cut, their lender wants more documentation, and the down payment they were building gets partially redirected to emergency expenses. Even when prices

soften, their ability to buy doesn’t improve as much as expected because the real constraint isn’t just the sticker priceit’s income stability and credit

access. Their lesson: affordability is a three-part equation (price, rate, and your personal balance sheet), and in a crisis all three can move at once.

2) The investor who “took a break” and missed the rebound

Another common experience shows up in investing. Someone sees the market falling, feels sick to their stomach, and sells “until things calm down.”

They don’t do it because they’re reckless. They do it because they’re human. The problem is that markets often snap back before the news gets better.

The investor waits for a clear signal“We’re safe now”but that signal usually arrives after prices have already recovered. Months later, they buy back in

at higher levels, effectively paying a “panic tax.” What they remember most isn’t just the loss; it’s the regret of realizing that the worst emotional

moment often coincides with the moment when discipline matters most.

3) The person who was ‘right’ but still lost

Sometimes people are directionally correct and still get hurt. An employee recognizes their industry is overheating and expects layoffs. They reduce

investing contributions to hoard cash. Then layoffs happenso they feel vindicated. But because they paused retirement contributions for an extended period,

they miss the lower-price buying opportunity that followed the downturn. Being “right” about a recession didn’t automatically improve the outcome.

The experience highlights a counterintuitive truth: the best financial plan isn’t the one that predicts the future; it’s the one that stays functional even

when you’re wrong (or when you’re right but the timing doesn’t cooperate).

4) The boring saver who quietly wins

Then there’s the least dramatic experience of alland often the most successful. Someone keeps a solid emergency fund, maintains manageable debt, and

invests automatically in diversified funds. During a downturn, they don’t love the statements they see, but they aren’t forced to sell. They keep buying,

because their paycheck still covers the basics and their plan doesn’t require perfect couragejust reasonable consistency. A few years later, when the

economy improves, they look “lucky,” even though what actually happened is that they engineered resilience. In a world where the alternative can be worse,

resilience is a superpower.

These experiences don’t excuse unfairness or erase frustration. They simply underline Carlson’s bigger point: outcomes are shaped not only by prices, but

by employment, credit, and the ability to stay in the game. If you want to benefit from opportunity, you have to survive the volatility that creates it.