Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What we mean by “lingering effects”

- A quick refresher: why the crisis hit so hard

- 1) The psychological scar tissue: markets healed, feelings didn’t

- 2) The policy hangover: low rates, unconventional tools, and “search for yield” culture

- 3) Regulation and oversight didn’t just increaseit evolved

- 4) Housing and homeownership: the scar that shows up in family photos

- 5) Work and wages: the slow burn recovery that shaped careers

- 6) Wealth and inequality: the recovery wasn’t evenly distributed

- 7) Investing behavior changed: the post-crisis playbook

- How to live with the lingering effects without letting them run your life

- Experiences and stories that mirror the lingering effects (extra section)

- The “I’ll buy when it feels safe” investor

- The homeowner who became a permanent renter (emotionally)

- The retiree who had to rewrite the script

- The small business owner who learned what “credit tightens” really means

- The young adult who inherited the vibe of risk aversion

- The financial professional who stopped believing in neat stories

The 2007–2009 financial crisis didn’t just break things. It rewired people.

And like that one friend who “totally moved on” from a messy breakup but still side-eyes every text message,

the economy and investors have carried a long memory ever since.

Ben Carlson’s core idea on A Wealth of Common Sense is simple and painfully human:

markets recover faster than emotions. Even years into a bull market, plenty of people still behave like the next

collapse is hiding behind the cereal aislequietly waiting to jump-scare them next to the granola.

What we mean by “lingering effects”

When people talk about the crisis “lingering,” they’re not saying we’re still living in 2008.

They’re pointing to aftershocks that changed behavior, policy, and the financial system:

the way we borrow, save, invest, regulate banks, and even the way we talk about markets.

Think of it like a big storm that knocked down a tree. You can clear the road quickly. But the soil changes,

the roots shift, and the neighborhood argues for years about whether trees are “worth it.”

A quick refresher: why the crisis hit so hard

The financial crisis was fueled by a housing boom, rising mortgage leverage, complex securitization,

and a banking system that turned “risk management” into a vibe rather than a practice.

When home prices fell and mortgage losses spread through the system, confidence evaporated.

Credit tightened, unemployment surged, and households watched wealth drop in a way that felt personal

because it was.

Even official histories describe the downturn’s financial damage as unusually large, with steep falls in home prices,

major stock-market drawdowns, and a sharp hit to household net worth.

That cocktail created the kind of memory that doesn’t fade just because a chart later goes up and to the right.

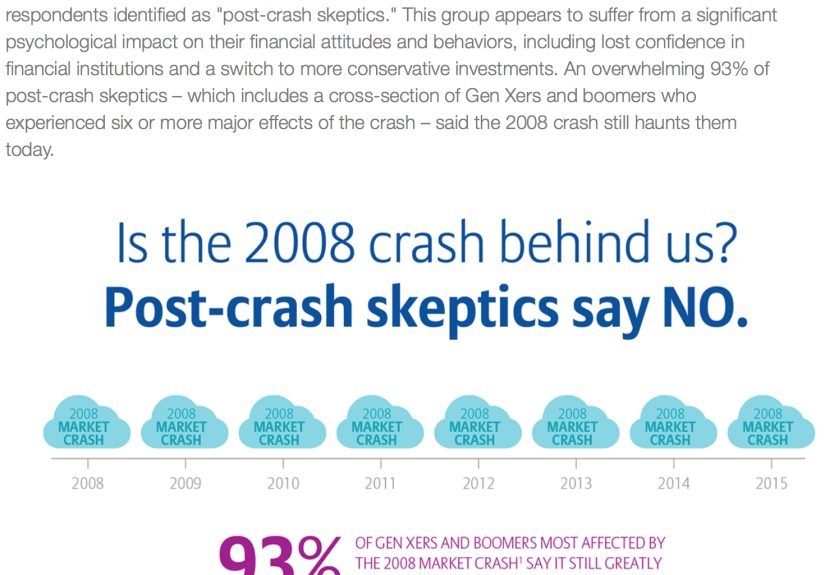

1) The psychological scar tissue: markets healed, feelings didn’t

Carlson observed something many investors recognize: years into a recovery, skepticism stays stubbornly popular.

Bad news is easier to believe. Optimism feels naïve. And every time the market hiccups, it’s treated like

an audition for the sequel: Financial Crisis 2: Now With More Tweets.

The media’s tone changed

Before 2008, parts of the media sounded like a hype squad for anything with “record highs” in the headline.

After the crash, the vibe shifted. Calling a bubble early became safer than missing one again.

That doesn’t mean warnings are always wrongjust that the incentive structure changed.

Investors became “anti-euphoria”

There’s a persistent post-crisis mood: people assume a boom-bust cycle is always around the corner.

Ironically, this can create a strange dynamic where markets rise while many investors never feel comfortable.

They wait for a “better entry,” and the waiting becomes a lifestyle.

Fed-bashing turned into a hobby league

In Carlson’s telling, blaming the Federal Reserve became a kind of sportone where the scoreboard is always

“the Fed is wrong,” regardless of what happens. The deeper issue isn’t that people debate monetary policy.

It’s that the crisis encouraged a scapegoat reflex: if outcomes feel unfair, someone must be cheating.

2) The policy hangover: low rates, unconventional tools, and “search for yield” culture

The crisis pushed the Fed into territory that shaped finance for years: near-zero rates, forward guidance,

and large-scale asset purchases (the stuff normal people call “what the heck is quantitative easing”).

These choices helped stabilize markets and the economy, but they also created a long period where:

safe yields were scarce. That scarcity influenced everything from retirement planning to corporate finance.

When bonds pay very little, people start looking at riskier assets the way hungry shoppers look at the “family size”

bag of chips: “I wasn’t going to… but now it seems like the only option.”

Why it mattered for everyday money decisions

- Savers felt punished when high-yield savings accounts weren’t really “high-yield” anymore.

- Retirees and near-retirees had to rethink income strategies (more laddering, more dividends, more flexibility).

- Investors learned the hard truth that “cash feels safe” can quietly become “cash loses purchasing power.”

The bigger legacy is cultural: a generation of investors learned markets can fall fast,

and a generation of savers learned “playing it safe” can still be risky.

3) Regulation and oversight didn’t just increaseit evolved

Post-crisis reforms weren’t only about writing new rules. They were about changing what financial stability

means in practice: more capital, more transparency, more stress testing, and more consumer protection.

Bank stress tests became a permanent feature

Annual stress tests and related supervisory programs helped formalize the idea that big banks should prove

they can survive ugly scenariosnot just promise they’re “fine, probably.”

Consumer protection became its own major lane

The crisis made it painfully clear that consumer financial productsmortgages, servicing, fees, disclosures

weren’t small details. They were systemic risk in street clothes. The CFPB was created to consolidate and strengthen

consumer protection authorities, influencing how lenders design and market products.

Deposit insurance and “trust infrastructure”

Confidence matters in banking. Changes like permanently raising the standard FDIC insurance limit to $250,000

reinforced the system’s “don’t panic” architecture. People don’t start bank runs because they love cardio;

they start them because they don’t trust the rules will hold.

Money market funds: making cash-like products more resilient

One underappreciated legacy: reforms aimed at reducing run risk in money market funds.

The crisis showed that “cash equivalents” can suddenly behave like “cash… eventually.”

Policy updates added tools like liquidity fees/gates and structural changes for certain fundsless exciting than a bull market,

but more important than a bull market when things get weird.

4) Housing and homeownership: the scar that shows up in family photos

Housing isn’t just an asset. It’s where kids grow up, where people anchor their careers, and where wealth accumulates

(or doesn’t). The foreclosure wave and housing crash shaped a decade-plus of choices: renting longer, delaying purchases,

and approaching mortgages with more cautionand sometimes, with fear.

The data show that homeownership rates fell for years after the Great Recession, with measurable drops among younger households,

and a slow rebound later. Meanwhile, research tracking borrowers suggests foreclosure can have long-lasting effects on credit

and borrowing behaviormeaning the crisis didn’t just knock people down; it also changed how willing they were to stand back up.

Long-term ripple effects in housing behavior

- Down payment psychology: larger down payments felt like “safety,” even when they delayed buying.

- Credit caution: many households treated debt like a stoveuseful, but you don’t touch it without mitts.

- Mobility trade-offs: tight credit and underwater mortgages reduced geographic flexibility for some workers.

5) Work and wages: the slow burn recovery that shaped careers

In labor markets, the crisis produced one of the most painful “lingering effects” of all:

long-term unemployment. When joblessness lasts months (or years), skills erode, confidence drops,

and hiring managers sometimes treat resume gaps like a personality flaw rather than a macroeconomic event.

BLS analysis highlights how unusually large the share of long-term unemployment became around the Great Recession,

and how that episode differed from earlier downturns. Those numbers weren’t just statisticsthey were delayed promotions,

postponed marriages, and “temporary” side gigs that turned into a permanent chapter.

The quiet scarring effect

Even after employment recovered, some groups experienced persistent disadvantages:

young workers entering a weak job market, households without a college degree, and communities hit hardest by housing and credit shocks.

The result: a recovery that looked decent in averages but felt uneven in lived experienceexactly the kind of mismatch that keeps distrust alive.

6) Wealth and inequality: the recovery wasn’t evenly distributed

One of the most widely discussed post-crisis legacies is how differently the recovery treated different balance sheets.

If you owned stocks and eventually stayed invested, you likely benefited from the market’s rebound.

If most of your net worth was tied up in housing in a neighborhood that recovered slowlyor you were forced to sell at the bottom

the “recovery” might have felt like a headline written about someone else.

Federal Reserve analysis has described an uneven “wealth recovery,” linked to differences in asset ownership.

Pew Research has also documented widening wealth gaps across groups in the years after the Great Recession.

The crisis didn’t invent inequality, but it accelerated certain dynamics and hardened them into a narrative people still argue about today.

7) Investing behavior changed: the post-crisis playbook

The crisis didn’t just produce new regulations and policy toolsit produced new habits:

More diversification (and more humility)

Investors became more aware that correlations can spike in a panic and that “I’m diversified” is a claim that needs receipts.

Asset allocation got more thoughtful for many people, less trendy, and more tied to goals and time horizons.

Passive investing grew up fast

While indexing was already growing, post-crisis skepticism about Wall Street’s incentives helped accelerate

a “keep it simple, keep costs low” mindset. Investors didn’t necessarily become anti-market; they became anti-nonsense.

Emergency funds became a financial identity

After watching stable jobs vanish, plenty of households treated liquidity like oxygen.

“Six months of expenses” stopped sounding conservative and started sounding like baseline adulthood.

How to live with the lingering effects without letting them run your life

If the financial crisis taught anything, it’s that risk doesn’t disappear when you refuse to look at it.

It just changes costumes.

A practical resilience checklist

- Match money to timeline: cash for near-term needs, diversified risk assets for long-term goals.

- Stress-test your plan: assume a downturn, a job disruption, and a surprise expense can happen in the same year (because… it can).

- Automate the boring: savings and investing habits beat motivational speeches nine times out of ten.

- Don’t outsource emotions to headlines: media incentives are not aligned with your retirement date.

- Learn the right lesson: “markets can crash” is true; “therefore never invest” is a career-ending overreaction.

Carlson’s warning is the most useful one: your past experiences can improve your decision-makingor trap you in a bunker.

The goal isn’t to forget 2008. The goal is to remember it accurately, so you don’t relive it unnecessarily.

Experiences and stories that mirror the lingering effects (extra section)

You don’t need a finance degree to understand the crisis’s aftertaste. You can hear it in how people talk.

Here are a few real-world patternscomposites of common experiencesthat show up again and again.

The “I’ll buy when it feels safe” investor

This person lived through 2008 and learned one lesson so loudly it drowned out everything else: stocks can fall.

So they kept money in cash for years, waiting for “certainty.” When the market rose, they felt annoyed.

When the market dipped, they felt temporarily validateduntil it recovered again.

The irony is that their risk wasn’t market volatility. Their risk was missing compounding.

They didn’t lose money dramatically. They lost money quietly, in the form of opportunities never taken.

The homeowner who became a permanent renter (emotionally)

Some households didn’t just lose a homethey lost a sense of control. Even years later, they describe mortgages like

suspiciously cheerful salespeople: “They say it’s fine… but they would say that.”

When the market improved, they didn’t feel relieved. They felt like they’d escaped a building that still smelled like smoke.

That fear can be rational in the moment. Long-term, it can also become a barrier to rebuilding wealthespecially

when renting costs climb faster than incomes.

The retiree who had to rewrite the script

Near-retirees felt the crisis like a deadline moving in the wrong direction. Some delayed retirement.

Others cut spending. Many became allergic to riskright when they needed their portfolio to work hardest.

Then came years of low rates, which made “safe income” harder to generate.

The long-term effect wasn’t only financial; it was psychological. People stopped thinking of retirement as a finish line

and started treating it like a flexible negotiation with reality.

The small business owner who learned what “credit tightens” really means

In normal times, “credit availability” sounds like a topic for economic reports. During the crisis, it became personal.

Lines of credit shrank. Loan terms changed. Banks that had begged for business suddenly wanted blood tests, fingerprints,

and a signed letter from your childhood best friend confirming you’re “good for it.”

Even after conditions improved, many small business owners stayed conservative:

more cash reserves, less leverage, and a deep skepticism of anything that depends on uninterrupted easy financing.

The young adult who inherited the vibe of risk aversion

Some people weren’t investing during the crisisthey were in high school, college, or just starting work.

But they watched parents stress, friends move, and “grown-up stability” wobble.

That memory shaped choices: delaying homeownership, prioritizing stable employers, and favoring liquidity.

In some cases, it also created a split personality with money:

conservative on the outside (budgeting, saving) and anxious on the inside (“what if the rug gets pulled again?”).

The financial professional who stopped believing in neat stories

Advisors, analysts, and planners who lived through 2008 often changed how they communicate.

They became less confident in predictions and more confident in process.

Instead of “here’s what will happen,” the message became “here’s how we’ll respond if it happens.”

That shift has influenced the industry: more focus on behavior, diversified planning, and stress testing goals

not just portfolios. In other words, the crisis helped finance grow up a little.

Not all the way, of course. This is still finance. But… a little.

The common thread in all these experiences is that the crisis didn’t end when the recession technically ended.

It lingered in habits, caution, narratives, and policy choices. And while that lingering can create resilience,

it can also create paralysis. The healthiest outcome is a middle path:

respect risk, plan for it, and don’t let yesterday’s fear steal tomorrow’s progress.