Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Quick refresher: what happens (with minimal spoiler drama)

- Why this early comedy hits different

- The Rankings: Characters, Scenes, and “Wait, What?” Moments

- Opinions that make this play click

- How modern productions make Two Gents work in 2025

- FAQ: Fast answers for curious readers

- Experiences related to “The Two Gentlemen of Verona Rankings And Opinions” (extra notes from the real world)

- Conclusion

Some Shakespeare plays arrive with a reputation so big you can hear it coming down the hallway.

Hamlet enters like a thunderclap. Romeo and Juliet arrives in matching hoodies.

And then there’s The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Shakespeare’s early comedy that shows up like:

“Hi! I’m still figuring myself out, but I brought a dog.”

This is a rankings-and-opinions guide for readers who want more than a plot recap but less than a 40-page academic paper.

We’ll rank the characters, the funniest bits, the most iconic “early Shakespeare” ingredients, and the moments that make modern audiences say,

“Okay… we’re definitely having a post-show conversation.”

Quick refresher: what happens (with minimal spoiler drama)

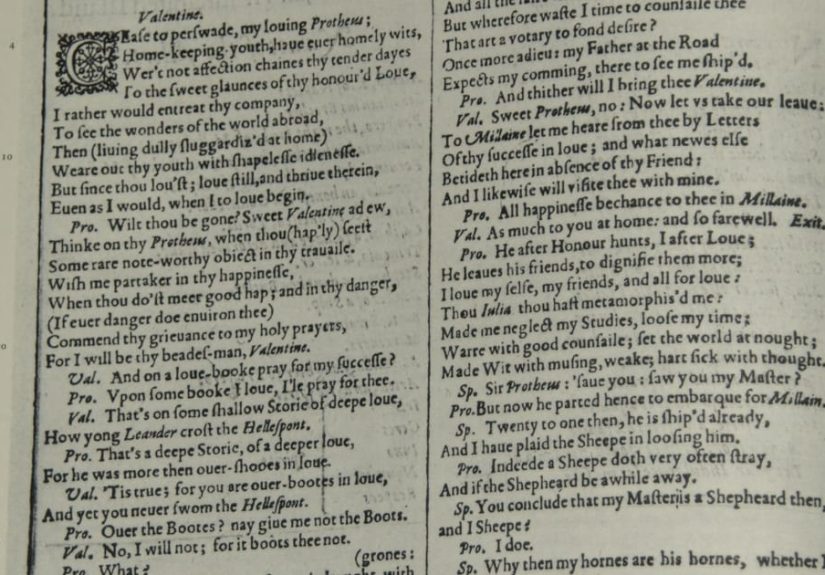

Two best friends from VeronaValentine and Proteushead toward adulthood the way many people do:

by leaving home, chasing love, and making choices that would absolutely get them muted in a group chat.

Valentine goes to Milan to become a “perfect gentleman.” Proteus stays behind for his girlfriend Juliauntil his father sends him to Milan too.

In Milan, Valentine falls for Silvia (the Duke’s daughter). Proteus arrives, sees Silvia, and immediately forgets he has a whole girlfriend back home.

He betrays Valentine, tries to win Silvia for himself, and Juliadetermined, clever, and not in the mood to be left behinddisguises herself as a boy

and follows him. There are rings, letters, servants who steal scenes, an outlaw band in the woods, and a famously messy final stretch.

Why this early comedy hits different

It’s a “prototype” Shakespearefull of future favorites

If Shakespeare’s later comedies feel like expertly plated meals, Two Gents is the test kitchen.

You can spot the ingredients he’ll keep using: disguise, love triangles, court politics, an “enchanted” forest vibe, and characters who grow up in public.

It’s youthful, fast, and sometimes hilariously blunt about how feelings can derail “good sense.”

It’s also where the play earns its reputation for… complications

The story’s big themesfriendship, loyalty, desire, status, forgivenessare compelling. But the play also contains an attempted sexual assault near the end,

and it resolves major betrayals with a speed that can feel emotionally unrealistic. For modern audiences, that means the play often works best when directors

approach it thoughtfully: making character motivation clearer, emphasizing consequences, and refusing to treat harm as a punchline.

The Rankings: Characters, Scenes, and “Wait, What?” Moments

Rankings are subjective by nature (and by design). These lists weigh three things:

(1) who drives the plot, (2) who earns audience sympathy, and (3) who still works onstage today.

Let’s begin where all Shakespeare debates begin: who’s the real MVP?

Ranking #1: MVP Character (Who actually carries the play)

- Julia The emotional backbone. She’s witty, determined, and surprisingly modern in how she navigates heartbreak.

Her disguise-and-pursuit storyline isn’t just a gimmick; it’s a window into how love, self-respect, and resilience collide. - Silvia Often underestimated. She’s not a passive prize; she resists pressure, chooses Valentine, and calls out Proteus’s behavior.

Productions that give her a strong spine tend to make the entire play feel smarter. - Launce (and Crab) Comedy with a pulse. Launce’s humor isn’t only wordplay; it’s character-based and physical,

and Crab is the rare “supporting actor” who can steal a scene by simply existing. - Speed The quick-tongued servant who keeps the pace brisk. He’s the play’s comedic caffeine:

a little sharp, occasionally chaotic, and always trying to move things along. - Valentine Romantic hero energy, with blind spots. He’s sincere and brave, but sometimes written like Shakespeare

is still figuring out how to craft consistent emotional logic for his leading men. - Proteus A compelling problem. As a character, he’s dramatically useful (he creates conflict).

As a person, he is… not invited back to the cookout without a very serious apology tour. - Thurio Comic “rich guy” suitor, more function than character. He exists to show that Silvia has options,

and all of them are worse than Valentine.

Ranking #2: Funniest moments (the bits that still land)

- Launce and Crab The man-dog relationship is legendary for a reason. It’s comedy built on frustration, affection,

and the universal truth that pets do not care about your monologue. - Speed’s banter and verbal sparring He’s the kind of character who would absolutely have a following on short-form video:

quick observations, sharp timing, and a knack for poking holes in romantic logic. - The serenade: “Who is Silvia?” A genuinely charming musical moment that many productions stage as a showstopper.

It’s sweet, performative, and slightly ridiculous (the ideal Shakespeare combo). - Letter-and-ring chaos Early Shakespeare loves “objects that cause feelings.”

Here, tokens of love become plot grenadesmisused, re-gifted, and weaponized. - Outlaws in the forest The play’s tonal pivot into “woods logic” is weirdly delightful onstage when directed with confidence:

suddenly we’re in a world where social rules bend and identity can reset.

Ranking #3: Most iconic early-Shakespeare ingredients

- Disguise and gender play Julia’s disguise drives empathy, irony, and suspense.

It also previews the later comedies where disguise becomes a full engine of plot and theme. - Friendship tested by desire The title promises “two gentlemen,” but the play interrogates what “gentleman” even means

when loyalty collapses under lust and status anxiety. - Court vs. countryside (and the forest as moral laboratory) Milan is rules and reputation; the woods are instinct and consequence.

Shakespeare returns to this contrast again and again. - Servants as truth-tellers Speed and Launce do what Shakespearean clowns do best:

they say the quiet part out loud, especially about love. - Big feelings, fast decisions This is an early play, and it moves like it’s late for something.

Characters fall in love quickly, betray quickly, repent quicklysometimes too quicklymaking it ripe for modern interpretation.

Ranking #4: Most questionable choices (a friendly roast)

- Proteus betraying basically everyone He breaks loyalty to Valentine, faith with Julia, and respect for Silvia.

It’s a masterclass in “How to become the villain of your own love story.” - The speed of forgiveness The play’s late-stage reconciliation can feel like it hits the fast-forward button.

Modern productions often slow this down emotionally, emphasizing shock, discomfort, or the cost of reconciliation. - Adults failing spectacularly at supervision The Duke tries to control Silvia’s marriage but seems to miss the chaos unfolding

right in front of him. The young characters operate like they’re unsupervised in a very expensive museum. - “Gentleman” as a social costume The play is obsessed with status training, yet the “gentlemen” behave badly.

That tension can be either a flaw or a themedepending on how you stage it.

Opinions that make this play click

Opinion #1: Julia is the heart; stage her like the lead

When productions treat Julia as a side plot, the play feels lopsided. When they treat her as the emotional center,

the story becomes a sharp coming-of-age tale: a young woman learning what love is (and isn’t), in real time,

while the men around her confuse desire with entitlement.

Opinion #2: The title is ironicand that’s the point

“Gentlemen” suggests virtue, training, and social polish. Yet the play shows “gentlemanliness” being built, performed, and sometimes faked.

Valentine and Proteus are essentially “gentlemen-in-progress,” learning (sometimes painfully) that character isn’t the same as a reputation.

Read that way, the play isn’t excusing bad behaviorit’s exposing how status can mask it.

Opinion #3: The dog isn’t a gimmick; it’s a theatrical strategy

Crab’s presence is funny, yesbut it also changes rhythm. A live animal forces actors to respond in the moment,

which can bring a risky early comedy into sharper focus. Done well, Crab becomes a symbol of what the play does best:

grounding ridiculous human choices in something real, physical, and immediate.

How modern productions make Two Gents work in 2025

1) Treat it like a story about teenagers with adult consequences

One smart lens is to frame the leads as impulsive young people (wealthy young people, specifically) testing boundaries

and learning what their actions cost. That approach makes the betrayals less “random plot” and more “reckless growth.”

2) Stage the final act with care, clarity, and accountability

The play’s attempted sexual assault and the rush toward reconciliation demand intentional direction.

Many productions emphasize Silvia’s agency, spotlight Julia’s perspective, and make forgiveness a complicated process rather than a switch.

A thoughtful staging doesn’t erase the discomfortit uses it to reveal the moral stakes.

3) Let the comedy breathebut don’t let it excuse harm

The servants’ scenes can be joyous. The forest can be wild fun. The serenade can be gorgeous.

The trick is balancing levity with truth: humor as contrast, not cover.

FAQ: Fast answers for curious readers

Is The Two Gentlemen of Verona Shakespeare’s first play?

It’s often considered one of his earliest surviving plays, and many guides label it an early comedy.

Whether it is the first is debated, but it clearly shows Shakespeare in an early stage of experimentation.

Why is the ending controversial?

Because the play resolves betrayal and harm quickly, including a major late-scene violation and a rapid pivot into forgiveness and weddings.

It can feel emotionally unearned unless a production carefully shapes tone, reaction, and consequence.

Who is Crab?

Crab is Launce’s famously “surly” dog and a consistent audience favorite. In performance, Crab can become a scene-stealer

simply because real dogs have perfect comedic timingpurely by accident.

What is “Who is Silvia?”

It’s a song in the play (often staged as a serenade) praising Silvia’s beauty and virtue. Productions frequently highlight it

as a musical centerpiece because it’s one of the play’s cleanest, loveliest moments.

Experiences related to “The Two Gentlemen of Verona Rankings And Opinions” (extra notes from the real world)

If you only encounter The Two Gentlemen of Verona as a summary on a screen, you might conclude it’s “minor Shakespeare” and move on.

But the experience of this play changes dramatically depending on how you meet it: on the page, in a classroom, in rehearsal,

or in a theater where a dog’s yawn can get a bigger laugh than a carefully crafted metaphor.

One common experience for first-time readers is whiplash. The opening sets up an intimate friendship, the kind that feels idealistic and earnest:

two young men imagining the world is bigger than their hometown. Then the plot turns into a stress test, and readers often find themselves ranking

characters almost automatically. Julia rises fast in those rankings because she behaves like a full human being. She makes mistakes, yes,

but she thinks, adapts, and learns. Silvia also climbs the list when you pay attention to her refusalsshe’s not simply “the girl,”

she’s a person pushing back against expectations. Meanwhile, Proteus tends to fall straight to the bottom because his choices don’t read as “romantic”;

they read as entitlement wrapped in poetry.

In group reading experiencesespecially table readspeople often discover that the comedy is less about “jokes” and more about rhythm.

Speed’s lines can land like stand-up when the reader commits to pace and precision. Launce’s scenes can feel like sketch comedy

because they’re built on a simple engine: he is emotional, his dog is not, and the universe is indifferent to his dramatic suffering.

That contrast becomes funnier the more seriously the actor takes Launce’s feelings. In many discussions, Crab becomes the surprise winner of the

“Best Supporting Character” category because Crab never lies, never betrays, and never launches into an apology speechCrab just exists.

Watching the play staged is a different kind of experience: it reveals what’s theatrical gold and what needs directorial help.

The serenade (“Who is Silvia?”) can be genuinely enchanting, especially when staged with playful energy or modern musical styling.

The forest and outlaw material can feel like an adventurous tonal shiftthe moment the play declares, “We’re leaving realism now.”

But the final movement of the plot is where audiences tend to split into camps. Some viewers react with shock at how quickly the play

tries to wrap everything up. Others focus on how productions handle that discomfort: whether Silvia’s experience is centered,

whether Julia’s reveal is treated as emotional truth instead of a convenient plot trick, and whether forgiveness is portrayed as complex,

conditional, and costly rather than automatic.

Another real-world pattern: people’s rankings shift after they learn a little context about “gentlemanliness.”

When you think of “gentlemen” as a social role being taughtstatus, polish, reputationthe title starts sounding less like praise and more like a question.

Are these two actually “gentlemen,” or are they practicing the performance of being gentlemen? That lens can make the play feel sharper,

because it turns messy behavior into commentary: class privilege plus adolescent impulse can create damage, and society often rushes to smooth it over.

Finally, there’s the “I didn’t expect to care” experience. A lot of readers begin this play as completionistschecking off Shakespeare titles.

Then Julia shows up with her determination and heartbreak, and suddenly the play is not just a curiosity; it’s a story about how people learn

(sometimes late) that love without respect is just appetite wearing a costume. And if you’re ranking the play’s lasting value,

that’s the category where The Two Gentlemen of Verona quietly scores higher than its reputation suggests.

Conclusion

The Two Gentlemen of Verona is imperfect Shakespearesometimes boldly charming, sometimes jarringly rough,

and almost always interesting as a snapshot of a playwright building his toolkit.

If you come for rankings, you’ll likely crown Julia (and maybe Crab) as the real winners.

If you come for opinions, here’s the big one: this play works best when you treat it as a coming-of-age story with teeth,

where “gentleman” is a role the characters are still learning to earn.